Black Narcissus (1947)

QFS No. 131 - The invitation for December 13, 2023

Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell are the powerhouse directing duo from England whose legendary work includes The Red Shoes (1948, QFS No. 52), The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), 49th Parallel (1941) with Laurence Olivier, The Tales of Hoffmann (1951), and of course this week’s selection The Black Narcissus. I’ve only scratched the surface myself with their career work but everything I’ve seen has been incredibly impressive. It’s no wonder they are so influential to the following generation of filmmakers – Martin Scorsese and Spike Lee to name two – and I feel they need to be studied further by us and future filmmakers.

One of the hallmarks of Pressburger and Powell is their masterly grasp of film craft. The cinematography in their films is legendary and was duly awarded throughout their careers. Their art direction, costumes and set design are unforgettable. I point you to The Red Shoes for a textbook in the complementary usof all those elements as a case in point. Their numerous Oscar nominations for screenwriting and several for editing illustrate their excellence in storytelling for the visual medium.

Black Narcissus is one of those films I should have seen already. I know about its enduring cinematography and some of the story elements, but I’ve never seen it. It’s a big oversight in my viewing history that I’m happy to remedy now. I’m excited to finally see it and continue with my exploration of Pressburger and Powell.

Reactions and Analyses:

The wind. Besides the sweeping vistas, the first thing you really become aware of in Black Narcissus is the wind. Before we even physically arrive at the monastery, the characters make mention of how the wind is unavoidable up there, on the cliffside in the Himalayas above the village in the valley below.

And throughout the film, the wind is a nearly constant. It blows the fringes of the habits of the nuns, shakes the flowering tree branches and the tassels on the drapes. No matter what anyone does, the wind can never be dominated. There is an uncontrollable force that can never be mastered out there all around you and it’s folly for anyone who tries to master it. Worse – the attempt to control an unseen force like that can lead to suffering and madness.

To me, this is one of the overarching metaphors of the film. A group of white nuns come to a palace no longer used in order to turn it into a missionary, to bring their teachings, medicine and religion to a place and people who believe in other ways of being. The group is small and recent; the people already there are ancient and vast.

One way of looking at Black Narcissus is that it’s an interpretation of British colonialism, specifically in South Asia. A small group of people, atop a hill looking down on and away from the locals, are trying to remake a world they’re not normally part of. And they cannot. They can’t control the primal, human nature of the place. (The nuns, are temporary – the winds live forever. India achieves independence from England in 1947, which is the year Black Narcissus is released so this is a very plausible interpretation as it would’ve been on the mind of writer-director Brits Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger.)

The wind took up a good amount of our discussion about the film. To one QFSer, the wind felt as if it represented the spirit of one’s past, haunting you. Another said he felt the wind revealed yourself to yourself, like a mirror in which you are forced to look at your own image and reflect. It reveals yourself to you. Several of the nuns have joined the order because they have a past they were trying to leave, especially Sister Clodaugh (Deborah Kerr). The solitude of the place, the natural elements, the long vista horizon – Sister Phillipa (Flora Robson) mentions she’s staring to lose faith upon seeing the infinite up there – forces each to confront something about themselves.

For Sister Clodaugh, she hadn’t even thought about her old lover since joining the order – not until she was up on the mountain at the monastery. Then the place, the wind, brought those memories back to her. The primal forces bringing to life primal emotions and urges.

It’s impossible to watch this film and not be utterly swept away by the filmmaking craft. If ever there was a film in which you could feel the hand of a master filmmaker carrying you along, it’s this. (Or master filmmakers to be more accurate.) Everything is tightly constructed and deliberate. The camera pushes in slowly in mid-conversation, but only when needed. Sister Coldaugh puts out her hand to shake Mr. Dean (David Farrar)’s hand, but he instead grasps it gently and squeezes ever so slightly – an intimate moment played entirely in a medium 2-shot with a wide enough lens that the action in the background of the nuns leaving can still be seen. I couldn’t help but say that producers on shows I’ve directed would’ve been horrified if I didn’t shoot a close ups on each person and then an insert on the hand to really hammer it home. But here, the directors choose to play it in a medium 2-shot – so simple, so perfect, and conveys intimacy, sensuality and their connection.

Pressburger and Powell also use canted/Dutch angles selectively but that are so well composed that one QFSer mentioned that they convey motion and movement without actually moving the camera. The close ups fill the frame, with extreme close ups on the eyes or on lipstick being applied to the lips. Contrast that with the wide vistas throughout the picture. The control and firm tightness of the film definitely evoked their The Red Shoes (1948) that the duo makes the year after this movie.

Speaking of those vistas, those matte paintings – for me, this is one of the greatest films ever shot on stage that looks like it wasn’t shot on stage. (One in the group disagreed with me so there’s a difference of opinion on that.) Another QFSer brought up that by using the images of the Himalayas in that particular style (black-and-white photographs painted with chalk), the filmmakers set up the painterly aspect of the film from the start. It’s not “reality” but it’s a painted reality – something that’s heightened and even more beautiful than reality. This painterly set up allows you to accept those vistas and the disappear into the story.

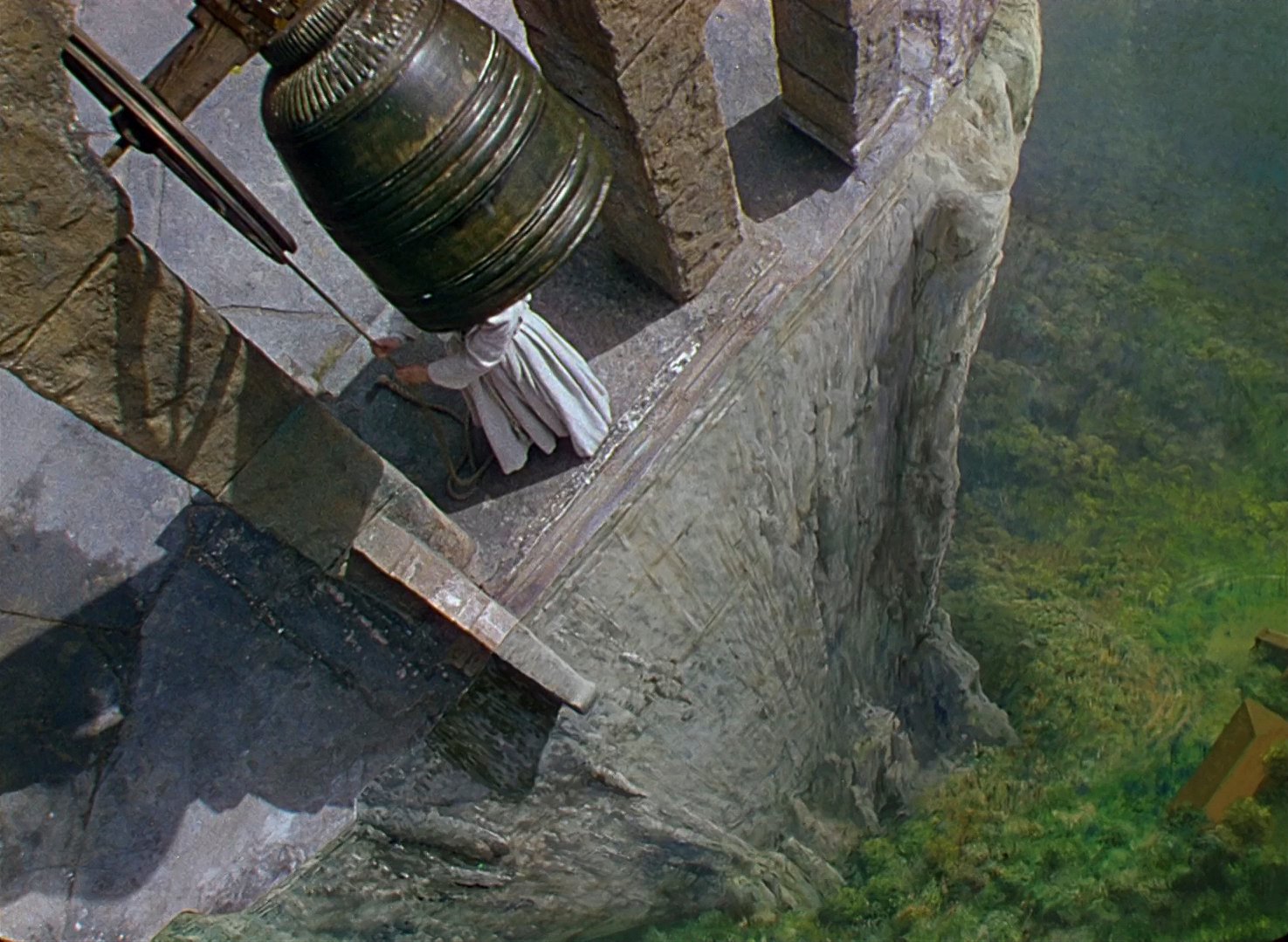

But it’s not just that they are beautiful, it’s what they represent. The vastness, the superiority of creation all around them, to me, makes the nuns not only smaller, but their mission almost meaningless and futile in the face of the abyss, the infinite around them. In particular, the part of the set with the huge church bell. The staging of this is astonishing. Not only is it on the edge and gives us a feeling that these nuns are all teetering on the precipice of stability, but the sheer (pun intended) technical feat of this – the directors had to have multiple matte painting backgrounds to simulate reality. There are the wide shots from behind the bell looking out towards the mountains. Then there are angles that show the bell, the nuns on the left of the frame, and the valley stretching out into the distance. And then, to top it off, there’s a high angle matte painting – a shot from above the bell looking down into the distant canyon floor below. All of these had to be conceived, planned out, then rendered in advance. The filmmakers couldn’t just walk on set and choose where to put the camera because they had to create that reality beforehand according to their vision in advance. It’s all so astonishing and inspiring.

It's been documented that Pressburger and Powell took inspiration from the Dutch painter Vermeer and his landscapes. A member of the group pointed out that it has a lot of single source lighting as well, evocative of the painting of Caravaggio. Which is no small feat for Technicolor stock that required far more light to properly expose than the human eye requires. Painterly is definitely an apt word for this film.

What genre is this movie? That is a question someone in the group asked. Of course, it’s drama – but could it also be a thriller, with a horror-like climactic resolution? There’s a warning early on by Mr. Dean that they won’t make it until the rains come. And, ultimately, that happens. But Black Narcissus in one way of looking at it is akin to a closed-room thriller where they all start to go crazy and then one attempts to kill one of them.

In an admittedly strange comparison, I brought up Danny Boyle’s overlooked Sunshine (2007) that features a mission to the sun to launch nuclear weapons into it in order to kickstart the failing sun’s heat. In Sunshine, everyone is on a mission, they start going crazy, and there’s somehow an entity on board who tries to kill them as the film goes on. It’s not a perfect parallel, but after seeing the slow burn of Black Narcissus there’s an argument to be made that this can be considered a thriller in many ways. (Another in the group brought up Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca, 1940, for its feel in the same filmmaking era.)

A QFSer brought up this exchange and its potential importance, which reflects the film’s title:

Young Prince: Do you like it, Sister Ruth? It's called Black Narcissus. Comes from the Army-Navy Stores in London.

Sister Ruth: Black Narcissus. I don't like scent at all.

Young Prince: Oh, Sister, don't you think it's rather common to smell of ourselves?

The group member’s assessment is that this is the thematic statement of the film. Here is something that’s being done to cover ourselves, to mask our natural scent. We humans all create a natural smell but we tend to hide it with something. For the nuns, it’s their faith masks their natural self (literally and figuratively), obscures their personal pasts. But you can only cover it – there’s the inner animalistic nature that we all have that either remains suppressed or emerges with time. And it can emerge in scary, deadly ways as it does with Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron).

In the scene where Sister Ruth puts on her make up – something that covers up something natural – Sister Clodaugh picks up the bible. Is this her cover? Is that what the directors are saying, that religion is a cover for the natural animal of ourselves? Perhaps, which sounds like a pretty subversive criticism of organized religion if that’s their intention.

There’s also something to the sadhu, the holy man who sits in reverent silence on the mountain top. Different religions orders come and go, but he remains there, unfazed. The image of an ascetic praying at the mountain, selfless, having achieved enlightenment and a oneness with everything around them is a common one in Hindu literary and religious traditions. Lord Shiva is often portrayed this way, long locks of matted hair, seated atop the Himalayas. This feels like the filmmakers are tying this into theme of colonialism trying to corral an ancient people and its faith, but it could also be an endorsement of a more mystical an ancient spirituality that worships out in the world and not confined within stone walls.

Left to right - Shiva statue atop Shiva Mandir in Bangalore (credit Darshan Karia), the holy man (uncredited or least I can’t find it) from Black Narcissus, Illustration of Shiva (artist credit unknown). Note Jean Simmons (Kanchi), the Indian bowing before him who is, notably, not actually Indian.

Which leads me to brown face. Do I Iike all the brown face, all the white actors playing South Asians in this film? I do not. I understand this is a “product of the time” and that argument is used as way to blow past criticism of using Jean Simmons (Kanchi), Esmond Knight (The Old General) and May Hallatt (Angu Ayah) as South Asians. But … come on. At the time they’re making Black Narcissus, India has a robust and growing film industry with many terrific actors who all are fluent in English. And though the film is being produced when the British are being finally kicked out of India, they are still intertwined in the Subcontinent. Pressburger and Powell could have easily gotten an Indian actor up to the standards of an international production and gotten them a ticket to London. I would almost buy the dearth-of-local-talent argument if Black Narcissus had been shot in 1946 Los Angeles where South Asians would’ve numbered at best in the dozens, as opposed to 1946 England where there are literally hundreds of South Asians at this time. As (soon-to-be-former) members of the British Empire who could study in London, just as Mohandas Gandhi and others had, there was a South Asian diaspora already living there. The production could easily have had a casting search for these actors but the fact is (and by that, I mean my educated guess) they simply didn’t want to because “at the time” people didn’t really care if they cast white Europeans and painted their face brown to make them ethnic. So it’s not lack of South Asian talent at fault here, but a lack of production effort. (Okay, end of rant. As a South Asian American, this rant has been my special privilege to contribute here.)

Aside from this (and from the utterly preposterous series of costume choices for Mr. Dean) Black Narcissus is an essential work. The conclusion is masterful. I was clutching my seat, not knowing who would die in the final scene. The deranged look of Sister Ruth – a look that one of our group pointed out must’ve influenced Stanley Kubrick a generation later – as she emerges, skeletal and red-eyed, as she emerges from the doorway is pure horror film perfection. And then that shot, looking up at Sister Clodaugh with the bell swinging behind her head as she gazes in horror down into the abyss has left an indelible imprint in my mind.

The final harrowing confrontation between Sister Ruth and Sister Clodaugh with its gripping imagery.

The rains eventually come and indeed, Mr. Dean is right – they made it until the rains but no more. You know it’s not a Hollywood film of the era. Here, someone at the beginning predicts the protagonists will fail and then they eventually do just that. There are scores of other films that would’ve seen these nuns triumph and overcome adversity. But the mission is doomed from the start. And in one of the final shots, the fog covers up the monastery high above as they are all leaving. This, like all of the shots in Pressburger and Powell’s masterpiece, is deliberate and not just a beautiful and poignant image. There are forces in the world that are too powerful for humans to control – from the external world to our inner nature – let alone comprehend, and an attempt to do so will certainly lead to doom.