Devdas (2002)

QFS No. 171 - Devdas is probably the apex Bollywood film, the type of film that screams “Bollywood!” especially if you’re not from India and you think “what makes up a Bollywood film.” The most Bollywood of Bollywood films.

QFS No. 171 - The invitation for March 26, 2025

For those of you who have been with us for a few years now, our Intro to Indian Cinema 101 is our most popular mini course, in that it is the only QFS mini course really. The films we’ve seen so far from the Indian Subcontinent cover the various distinct areas and eras of the world’s largest and multi-faceted filmmaking region. As a recap, this is what we’ve watched and discussed, in chronological release order:

● Apur Sansar (1959, QFS No. 16), directed by Satyajit Ray, as part of the Apu Trilogy and the origin point of Indian Art Films (aka Parallel Cinema), what we would call in the US as an independent film. Also launches indigenous Indian cinema into the consciousness of the global filmmaking community.

● Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959) directed by Guru Dutt, representative of the Golden Age of Bollywood directed by an auteur, a classic musical with melodrama at its heart but an adherence to high aesthetics and artistic cinematic quality.

● Sholay (1975, QFS No. 62) directed by Ramesh Sippy, Indian “Western” with megastar Amitabh Bachchan. With India’s first (sorta) 65mm film, the country is starting to be influenced more by international filmmaking, including Hong Kong action films and American Westerns, as it grows into its young nation 30 years after independence.

● Dil Se.. (1998, QFS No. 32) directed by Mani Ratnam, represents an example of the influence of MTV on Indian cinema, music videos and the opening of Indian media markets to the West. (Also stars global megastar Shah Rukh Khan, who is the star of this week’s selection Devdas.)

● 3 Idiots (2006, QFS No. 118) directed by Rajkumar Hirani, a comedy that’s a portrait of a more modern Bollywood film that’s more (sorta) self-aware than its predecessors and adapted from a successful Indian novel.

● RRR (2022, QFS No. 86) directed by S.S. Rajamouli, an example of “Tollywood,” or films from the Telegu language film industry – technically not a Bollywood film, which are in Hindi. An example of a rare global megahit from a regional film industry. Also an example of India’s embrace of digital filmmaking technology on a massive scale.

● Additional subject material: international films by non-Indian directors that take place in India: Gandhi (1982, QFS No. 100) directed by Richard Attenborough and The Darjeeling Limited (2009, QFS No. 59) directed by Wes Anderson.

That’s actually quite a lot of films about or from India over five years when it’s laid out like that!

So where does this week’s selection Devdas fit in? Devdas is probably the apex Bollywood film, the type of film that screams “Bollywood!” especially if you’re not from India and you think “what makes up a Bollywood film.” The most Bollywood of Bollywood films. You get what I’m driving at – melodrama, colors, costumes, passionate forbidden love, beautiful people, romance, the greatest choreography, set design and cinematography to enhance it. Devdas feels like it crosses eras, influenced by the gaudy past of Indian Hindi films but unleashed into the modern world. It features screen darling Madhuri Dixit of the 1980s and 1990s, giving way to screen darling Aishwarya Rai*, star of the 2000s. And of course, SRK, Shah Rukh Khan in the center at the ascent of his stratospheric career.

Devdas, also is the most adapted story for the screen of all time – the 1917 novel has been adapted 20 times in multiple languages since the 1928 silent film version! This is as classic an Indian tale on the screen as can be told. Join the discussion below!

*Roger Ebert once said (paraphrasing here) Aishwarya Rai is the second most beautiful woman in the world. When asked who was the first, he said, Aishwarya Rai is also the first. You decide!

Reactions and Analyses:

There is no medium, there is only maximum.

Modern Hindi films (aka Bollywood films) are not known to be subtle. They are, by and large, maximalist, gaudy, extreme in their emotions and light on nuance or finesse. And the most extreme of those extremes are the films of Sanjay Leela Bhansali, and in particular the opulent Devdas (2002) – perhaps the most maximalist of modern Bollywood films.

Devdas is the peak, the most Bollywood of Bollywood films. One line of dialogue in particular stands out as an unintentional descriptor of Bollywood films. The titular character Devdas (Shah Rukh Khan) wallows in self-pity and self-destruction for a better part of the last third of the film. His family friend Dharamdas (Tiku Talsania) warns him that he’s drinking to excess. To which Devdas replies rhetorically, “Who the hell drinks to tolerate life?!” There’s only abstinence and inebriation for Devdas, only extremes, nothing in between.

Similarly, who makes a modern Bollywood film to explore subtlety? (The answer to the drinking question also should be the answer to the Bollywood one – lots of people!) Swinging along from one extreme to the next throughout Devdas is an enjoyable endeavor to be sure, highs and lows abound. Bhansali takes the well-known Indian story and gives it the appropriate operatic treatment it deserves.

Star-crossed lovers, Indian style – that’s Devdas. Opposite Devdas is Paro (Aishwarya Rai), photographed in the most glamorous way imaginable, usually bathed in a soft light and equally soft portrait lenses. The imagery evokes the classic cinema of American films of the 1930s, when closeups were glorious and beautiful and stood out from the rest of the film. Truly, it takes very little to make Rai look beautiful, but Bhansal and cinematographer Binod Pradhan elevate every moment she is on screen. Extreme beauty aligns with the extremes throughout the film.

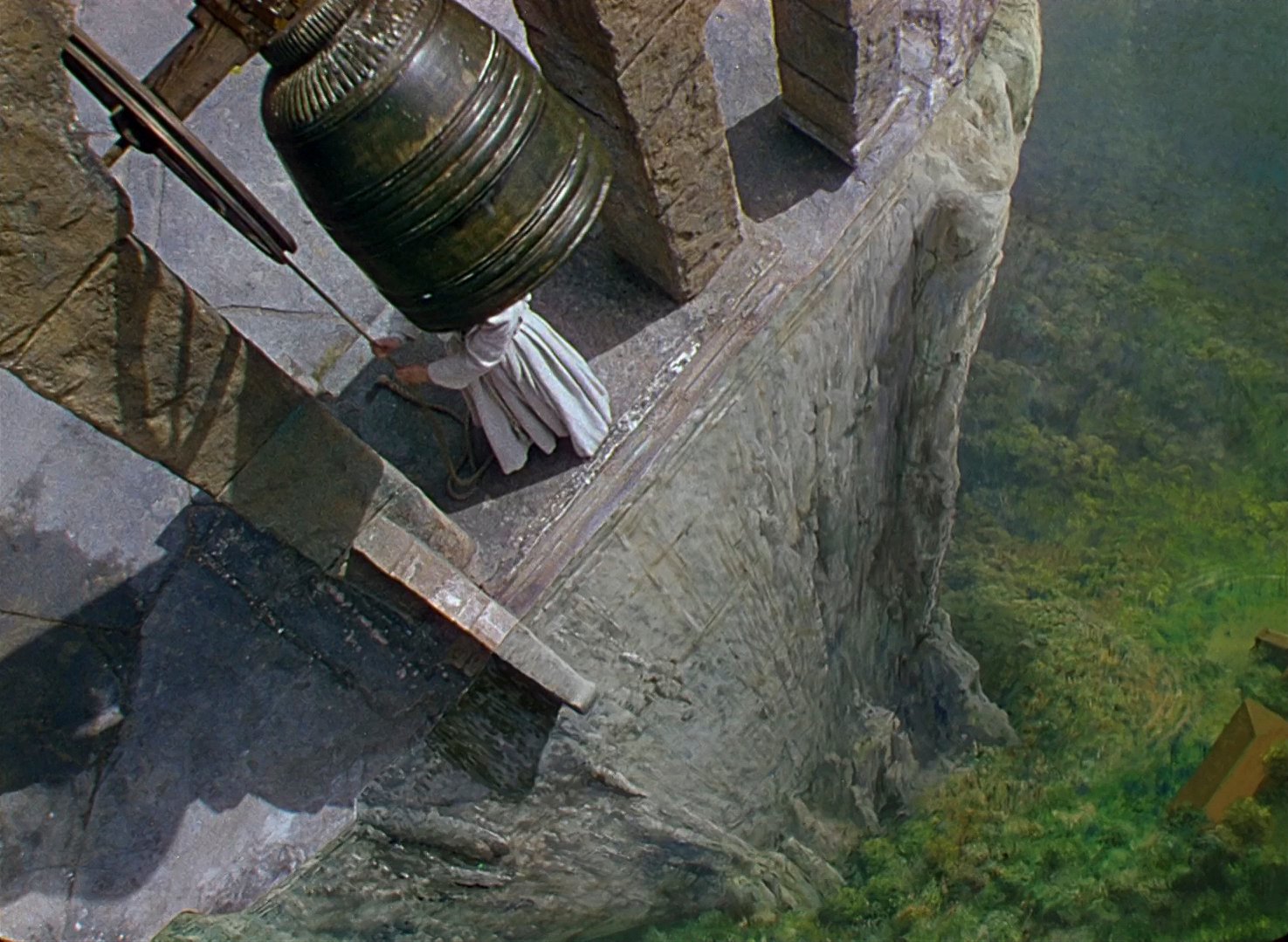

Devdas executes the operatic scope befit a melodrama – massive (truly massive) beautiful stained-glass sets, shimmering (and heavy) costumes in the traditional Indian classical style with modern twists, exquisitely choreographed dancing sequences – all enhanced by synchronistic cinematography to capture it all. It isn’t simply the use of color and costume and camera work, but the synthesis of all together in harmony and in concert with each other. The dancers in twirling lehengas are nice, but the overhead shot to show the symmetrical pattern of the dancers and the fabric spinning in unison with the music is what makes Devdas a stunning work of film craft.

One of the hallmarks of Bollywood cinema is dramatic character introduction. The filmmakers know that their audiences come for the melodrama, the spectacle, but most of all the larger-than-life stars who loom as large as gods and goddesses on and off the screen. Take the first time we meet Paro – for a long time her face is hidden. She dances with the other women in anticipation of the imminent return of her childhood crush, her beloved Devdas. We learn about the candle that has been literally (not figuratively) burning since he left, a flame that cannot be extinguished. But her face, throughout this sequence, remains cleverly hidden by camera work, blocking and choreography. Then she dances onto the balcony where a storm continues to rage.

A lighting strikes, a flash fills the sky and the shot cuts to Paro’s face, literally glowing in the flashing light, a vision of beauty and yearning. It’s fantastic. The filmmaker knows what’s important – the power of the close up of his stars. Throughout, Paro’s yearning close ups, as well as Devdas’ and later Chandramukhi’s (Madhuri Dixit) close ups, tell the story of love, anguish, sorrow, hope, desire. Behind Chandramukhi, a courtesan, the gold mirrored tassels that hang in her brothel shimmer like stars behind her when she speaks in her domain. It’s overdone and extreme but that’s the point.

What point is there in filming to tolerance, after all?

There is no let up in the melodrama and the full-throated extremes of characterization. You suspect Kalibabu (Milind Gunaji) must be one of the “bad guys” immediately. Why? Well who else would have a mustache like that? Only someone with the inclination to commit evil, according to Bollywood logic.

There are other conventions of Bollywood that Devdas adheres to. Up until recently, Indian films refrained from overt acts of love on screen - no kissing, certainly no nudity, PG-13 at most by American standards. This puts Indian films squarely in line with American filmmaking of the 1950s and earlier, with suggestion being more powerful than actual directness. And Devdas has suggestive scenes to the extreme. Take the scene with Paro and Devdas by the riverside, intercut with her mother Sumitra (Kirron Kher) dancing for Devdas’ mother Kaushalya (Smita Jaykar) at a party. The scenes by the river are incredibly seductive, bathed in moonlight, as Devdas tries to remove a thorn from Paro’s foot, the music of “Morey Piya” swelling as the scene cuts between Devdas’ home and at the riverbank. It’s clear, at least to me, that this scene between the two lovers suggests they are making love (off-screen of course), the blue waterfall behind them, the setting awash with lusty romance.

And despite all the technical mastery for most of the film, there are a number of scenes that feel as plainly shot and amateurish as an Indian television soap opera. Probably because, at it’s core, Devdas is a soap opera, a melodrama. The evil sister-in-law Kumud (Ananya Khare), jealous of the lower class but beautiful Paro, tries to prevent her from marrying the higher class Devdas. She manipulates Devdas’ mother Kaushalya by whispering poisonous doubts into her ear. Paro’s mother Sumitra is humiliated by Devdas’ family and forbids Paro to marry him, setting of the cascade of tragic events that follow for the next three hours or so. These scenes, however useful they are for the plot, if cut together separate from the rest of Devdas, would appear as if they were from a different film. For someone who didn’t grow up with a steady diet of Bollywood films, these scenes felt excruciating. If the rest of the film was so innovative artistically elevated, why are these other scenes the opposite?

Regardless, the film captivates. Though it’s been told many times on screen, I didn’t know the story myself. After Devdas has nearly drunk himself to death and strives to go to Paro – now married to another wealthy man who doesn’t love her – Devdas collapses at her gate, about to breathe his last breath. Paro races through her palatial home, her white gown flowing down the massive staircase and sprinting through the halls. Her husband’s guards attempt to slow her down and begin to shut the gate. And at this point, I truly had no idea what would happen. I thought for sure Paro would reach Devdas, the two would finally be together, and her love would resuscitate him, save him, and they would live happily ever after.

The gate closes, red leaves from the tree above Devdas drift downwards, and they are separated forever by his death. It’s a riveting sequence, made the more stunning if you don’t know the outcome of this story and hadn’t grown up with it like everyone in India has. I found myself truly shocked and moved, in awe of the filmmaking but captivated by the frenetic what-will-happen narrative at the end.

There is no comparison in the West, really, to this type of uniquely Indian film. While Bollywood has been influenced by American and European filmmaking to some extent – look at Hollywood glamour of the 1930s including Busby Berkeley’s musical choreography and you’ll see commonalities – there are no purveyors of this level of melodrama and craftsmanship outside of the Subcontinent. Baz Luhrmann probably comes closest, especially Moulin Rouge (2001) and Elvis (2022). I’d say you could even throw in John Chu, but even his Wicked (2024) is more classic American musical than Indian Hindi film melodrama.

Perhaps we in the West need this. Perhaps we need more of the maximalist movies, bathed in colors and sound and music and tears and laughter and deep sadness and exquisite beauty. There’s a catharsis, or more accurately a chance to disappear into a world that completely envelopes you to the max. Why else make a film but to go to the extreme?

The Seed of the Sacred Fig (2024)

QFS No. 168 -The Seed of the Sacred Fig has been on my list since I saw a riveting trailer and have read a little bit about the film. Shot in secrecy in Tehran, this will be our second film from Iran, after the terrific A Separation (2011, QFS No. 49), directed by Asghar Farhadi.

QFS No. 168 - The invitation for March 5, 2025

The Seed of the Sacred Fig (2024) has been on my list since I saw a riveting trailer and have read a little bit about the film. Shot in secrecy in Tehran, this will be our second film from Iran, after the terrific A Separation (2011, QFS No. 49), directed by Asghar Farhadi. A Separation and his following one The Salesman (2016) both won the Academy Award for Best International Film, making Farhadi the only filmmaker from the Middle East to direct an Oscar-winning film in this category – and he did it twice.

The Seed of the Sacred Fig could’ve made Mohammad Rasoulof the second filmmaker to do so, but I’m Still Here (2024) took home the prize this year. Still, looking forward to seeing this our second selection from Iran (via Germany) - join the discussion!

Reactions and Analyses:

The idea of Chekov’s gun – that if you see a gun at the beginning of the story you need to see it be fired later on – is what appears to be the initial setup of The Seed of the Sacred Fig (2024). The very first shot are bullets being dropped onto the table and a gun handed to its new owner, Iman (Missagh Zareh). Moments later, it’s on the passenger seat as Iman drives away, the camera tilting down to reveal it, overtly drawing out attention to the weapon.

But for so much emphasis on the gun and the thriller-style opening of the film, the gun ends up being only a very small part of the film for the entire first half – so much so that it’s almost forgotten, the way Iman inadvertently forgets it in the bathroom until his wife Najmeh (the incredible Soheila Golsestani) discovers it one day. She’s already let him know that she’s not thrilled with having a gun around. But what we don’t yet realize is that this is all a long setup by filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof for a payoff later on. What we learn later is that the gun is more than a gun in this present-day Iran – it’s a symbol. It represents state power, and Iman will be a proxy for the people who wield that power.

To get there, the filmmaker focuses on the very real protests of 2022 unfolding in Iran with women standing up to the country’s misogynistic totalitarian regime, refusing to wear hijabs and standing up to the very real possibility of harm and death. In The Seed of the Sacred Fig set against this backdrop, Iman, an investigator trying to climb the ranks within the government, discovers in his new role that he’s supposed to rubber stamp death warrants without really looking into their veracity. He’s not thrilled about compromising his morals and is caught in a bind, and Najmeh talks him through his obligations. This, too, seems like a setup by the filmmakers about a man with a moral dilemma.

Their two young daughters, one a college student, Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and the other Sana (Setareh Maleki), a teenager, are firmly in the crosshairs of the forces of change roiling their city and country Najmeh tells her children that they must dress modestly and avoid any hint that they are anything other than rule abiding because her father’s promotion depends on it – though they don’t know exactly what their father does. And besides, they’ll get government housing if he’s a judge and they’ll each have their own rooms.

But the forces of the world can’t be kept out because of social media. And here, the filmmakers are very inventive (perhaps too much?) with their use of real-life footage posted online at the time. The government was able to control their people in darkness, but with the light of videos and media, it’s a different story. Sadaf (Niousha Akhshi), Rezvan’s friend, is injured at a protest, shot in the face with buckshot. Secretly brought into their home, bleeding, Najmeh – despite very vocally opposing the protests and the women involved – patiently removes each pellet from Sadaf’s face. It’s a wrenching, horror-filled scene told in two close ups with the music rising, tight shots of bullets being removed cut with the mother’s stricken face, holding back tears. This is textbook in visualizing a character’s turning point – we see it in Najmeh’s face: this could’ve been her daughter.

She’s not all the way convinced the protests are good, but she knows that even innocent women – children – are caught in the crossfire. Later, the girls find out that Sadaf is taken away after she returned to college but nobody knows where she is. And Najmeh tries to get information covertly from Iman, without betraying that it’s someone they know for fear of getting him into trouble. She seeks out a family friend, Fatemeh (Shiva Ordooie) for information through Fatemeh’s husband who also works for a secret faction of the police.

And throughout all this, Najmeh’s concern remains mostly domestic. Her husband works too much and she pleads with him that her daughters need their father, especially now. He reveals that the arrests have escalated so much that he’s up all day rubber stamping guilty confessions.

Finally, the family is able to sit down and have dinner, but it leads to an inevitable explosive fight. The girls know what’s happening through social media, through the injury to Sadaf, that the people who might be injured are innocent and their lives are being destroyed just because they don’t want to wear the veil. Iman says they are misled by people with ill intentions, by women - whores, he believes - who want to walk around naked on the streets. The fight is vicious and ends with Najmeh firing back at the girls we finally had a dinner together and you ruined it.

All this time – the gun is not even remotely a part of the story. In fact, the entire QFS discussion group forgot its existence by and large except as an accessory carried by Iman. So when the gun disappeared, it truly was a surprise as much as it was a mystery. Iman can’t find it and Najmeh scramble to locate it. The children never even knew the gun was in the house, but they become Iman’s the primary suspects.

And it’s at this point the film kicks into overdrive and leaves the outside world’s tumult and brings it inside. Consumed by paranoia and fear of being imprisoned for his negligence, it’s a riveting next hour or so – in part because we really have no idea who could have taken the gun. Several of us believed he must’ve just lost it, which is set up nicely by the filmmakers as mentioned earlier when the overworked Iman accidentally left it with his clothes on the laundry hamper.

Instead of accepting that he could’ve possibly made a mistake, Iman assumes his family must’ve taken the gun. It’s unfathomable that someone in his position could do something in error, so he turns his ire and focus on the family. He makes Najmeh search the children’s room, turning everything inside out. She thoroughly searches the home and cannot find it. Iman begins to unravel and follows his colleague’s suggestion to have his children professionally interrogated by their mutual friend Alireza (anonymous actor). When you have your children professionally interrogated, you may have gone past the point of no return.

And in many ways, he has. The interrogator is certain it’s Rezvan, the college student. But she vehemently denies it. Further escalating Iman’s paranoia is that protestors have been finding people who work for the regime in secret and posting their names and addresses online – which is what happens to Iman. His colleague suggests he leaves with his family for a few days, is given a backup gun, and decides to go to his ancestral home. But before that, he drives home in a terrific sequence that showcases Iman’s paranoia. Everywhere he looks he thinks people are following or watching him. He looks over at a young woman driving next to him without a hijab and notices her small neck tattoo – is she one of these loose women, one of his enemies? A motorcycle seems to be driving a little too close – is that someone following him or is it just normal traffic? He gets home and sees someone on a cellphone outside their apartment building – is that someone keeping tabs on him, or is he waiting for a friend?

Iman is forced to experience life the way people without power live under the totalitarian regime of the country. The filmmaker has cleverly set this up throughout the film with echoes of Brazil (1985, QFS No. 158) or George Orwell’s dystopian 1984 as unavoidable comparisons. The state can turn on one of its own; no one is safe from the state’s mindless cruelty. And all of this seems like it’s going in that direction– a story about a man who is part of the system becomes a victim of that very system, leading him to question the system itself and his place within it, to perhaps renounce or even move to transform it.

That is not what Rasoulof does. Iman still convinced that one of his family took the gun and the final portion of the film devolves into a chaotic madman, unable to love his own family any more, becomes the cruel embodiment of the country’s leadership, still convinced that one of the three women in his life have stolen the gun. And in fact, one has! The one no one suspected, the younger daughter Sana. But Iman doesn’t know that yet, which makes for more suspense. After running two people who have recognized him off the road, the family arrives at the abandoned, dusty desert homestead of his youth where he locks the family in a room until they come out and reveal who has the gun. It escalates with Iman locking all of them in the room – except Sana who has escaped with the gun.

And there it has returned, Chekov’s gun, waiting to be fired. The final chase, though perhaps longer than it ought to be and slightly illogical, is still suspense filled and in a great location that evokes the longevity of Iran and Persia – something older than the mores of the current Iranian regime. Sana has the gun and Iman, who has another gun, chases her with the two others scrambling. I found myself wondering what is the desired outcome here? I don’t want Iman to be shot and killed, but I don’t want the women to suffer either. But what then? It makes for great drama that ends with Sana unable to shoot Iman except into the ground at his feet, where her father then collapses under the ancient sand walkway and is swallowed by the land itself.

Though Rezvan and Sana are Iman’s flesh and blood, he has become unable to see them as such in this final sequence, only concerned about his own ambition and safety. He seems prepared to kill his daughter Sana, even taunting her that she doesn’t know how to shoot. The filmmakers have chosen to have Iman embody the state – he is modern Iran’s government, unmoved and unwilling to bend.

It's a choice that feels like perhaps more symbolism than rooted in reality. Would a father actually do that? Would he forsake all of his memories, his love for his wife, seeing his children grow, all of their history together, because he’s been blinded by power and control? The filmmakers seem to say, yes, this is what totalitarianism does to ordinary people. Iman is the state and the state can only be eliminated, not changed – that’s what the director seems to be saying

Rasoulof can’t be faulted for any of these choices. After all, he’s been a victim of the regime for what appears to be his entire adult life. Much has been made about the fact that he filmed this movie entirely in secret over a 70-day period, and had to escape the country to arrive at the Cannes Film Festival for the premiere. So when we criticize the excessive chase sequence at the end or the imperfections in the conclusion of the film – aren’t the women now in even more danger and will be heavily questioned about the whereabouts of their dead husband/father? – all of this might have to be taken with a grain of salt (sand?).

What an extraordinary feat of pure will to make this film under circumstances we, living in the West, couldn’t possibly imagine. Sure there are a handful of plot holes, including how did Sana know there was a gun in the house and where it was and how did she hide it during the search, but as a group most of us found ourselves easily forgiving much of this given the larger scope of the film and the extreme lengths Rasoulof went to make it.

His filmmaking is incredibly savvy, using real footage shared on social media with even a nod to YouTube as a way to learn about all things, including how to load and fire a gun. This element of the old Iranian overlords unable to contain the new information-laden world is a fascinating additional angle to both The Seed of the Sacred Fig and the true protests that swept the nation in 2022 and beyond. For Rasoulof to pull all of this off in a contained thriller, a family social drama, and a commentary on society, the film is an extraordinary piece of filmmaking – both creatively and production-wise. While everyone might not agree on the story and ideas contained within the film itself, it’s hard not to take inspiration from the execution and commitment to telling a story like this against all the unimaginable odds to do so.

Chungking Express (1994)

QFS No. 162 - Happy New Year! We resolve to watch movies and argue about them in a constructive manner!

QFS No. 162 - The invitation for January 8, 2025

Happy New Year! We resolve to watch movies and argue about them in a constructive manner!

We last watched a film from the great Wong Kar-wai in 2023 with his In the Mood for Love (2000, QFS No. 105) – another favorite of mine. Now, if you have watched In the Mood for Love and found the pace a little too languid for your taste, I assure you that Chungking Express is vastly different on that account. It’s actually somewhat surprising that the same filmmaker made both films when you see them side-by-side, with Chungking Express flying a little more kinetically than the rhythmic, elegant pace of In the Mood for Love.

I first watched Chungking Express on what was likely a bootlegged VHS tape that a fellow AFI Fellow had obtained and snuck in a viewing at school back in 2000 when the film was not in wide distribution in the US. The film blew me away and that started my long, steady trek towards Wong Kar-wai becoming one of my favorite filmmakers of all time. And in case you like lists, Chungking Express is No. 88 on BFI’s Greatest Films of All Time list (In the Mood for Love is No. 5, incidentally).

Chungking Express is a film that fills me with joy, and I feel like we’ll need a lot of that this year – so why not start the year off this way? Join us in the discussion!

Reactions and Analyses:

What is it like to live in a city? A city, teeming with life, with people, with corners unexplored and places undiscovered. At times exciting, at times isolating, paradoxically producing loneliness amidst the masses. Serendipitous, concealing, frantic and sleepy all at once. In this, the city, Wong Kar-wai paints a poetic, chaotic mess in Chungking Express (1994).

So often when writing or thinking about a movie or a television show, we use the expression “the city is a character.” In films where this is truly the case, the city has become more than a backdrop or a setting, but directly influences the characters’ decisions and actions. New York takes on this quite frequently, with probably Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) being the most clear example of this.

The city block in Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989) is not just a setting, but its very dynamic of race and class influences the narrative. You could argue that in John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood (1991, QFS No. 12), the protagonists’ Los Angeles neighborhood influences how they behave, what they attempt to achieve, how they try to survive. Rio de Janiero explodes to life in Walter Salles’ City of God (2002) and is as much an influencer of the narrative as any film about a place. Lost in Translation (2003) for Tokyo, Mystic River (2003) for Boston, maybe even Blues Brothers (1980) for Chicago - a place oozing with music at ever turn.

In Chungking Express (1994), Wong Kar-wai captures Hong Kong at a particular inflection point in history. On the eve of the handover of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom back to the China, the city is a nation state, influenced by the West and the East, a crossroads but more than that. The ancient city is crisscrossed with oddities that span the old and the new – an outdoor moving walkway next to Cop 663’s (Tony Leung Chiu-wai) home, a cloth-covered vegetable market near the Coca-Cola adorned Indian food stalls. The cold iron and steel and neon of a city but the red and swish of color of fruit merchants and factory produced goods. The Indian goods makers, the Chinese shop keepers, the European drug dealer/bar owner.

One comparison that came up in our QFS discussion was Slumdog Millionaire (2008), and specifically its portrayal of a city. The time frame of Chungking Express and Slumdog Millionaire are different - Danny Boyle’s film takes place over the protagonists’ childhood into adulthood as opposed to the very compressed time in Chungking Express - but both capture a city at an inflection point. In Slumdog Millionaire, “Bombay became Mumbai” says Jamal (Dev Patel), which is to say a sprawling Indian city became an international megalopolis complete with wealthy homes and, to the main narrative point, fancy game shows. But it’s this moment in time, when slums are about to be turned into high rises and the messy city that grew up as a child of British Empire, Indian Kingdoms and Indian Democracy will accelerate into a new iteration. Hong Kong is similar, another child of Empire and an in between democracy, is on the verge of something new. It’s that energy that Wong Kar-wai so adeptly harnesses throughout Chungking Express.

But it’s not just the vibrancy of the city that concerns the filmmaker, but how a city influences the people who dwell within it. The men, Cop 663 and He Zhiwu, Cop 223 (Takeshi Kaneshiro) are sad poets, so caught up in their own loneliness that they are unaware of something critical right in front of their noses. He Zhiwu doesn’t realize that the blonde woman he’s falling for (Briggitte Lin) is the very woman that his police force is on the search for after she went on a vengeful shooting spree. And Cop 663’s apartment life continues to improve, somehow, though he’s completely unaware an elf is the one doing the improving – Faye (Faye Wong), who is either smitten or just mischievous and craves a mission. In a city, she can slink through unnoticed among the masses, infiltrate 663’s home, and return to work without anyone being the wiser - just one of a million people on their own solitary task.

The isolation the men feel in the city manifests differently for both men. He Zhiwu seeks out companionship actively, calling women he’s known – even ones he hadn’t spoken to since grade school or ones that now have children. He’s obsessed with an ex-girlfriend and buys cans of nearly-expired pineapples with her name, May, on it. Cop 663 communicates with his “community” of inanimate objects in his home after his air hostess girlfriend leaves him. He gives his wash rag a pep talk and expresses disappointment in his toothbrush. It’s the women, the connection of people accidentally thrust together in the sprawling metropolis that bring life to these men, that bring them out of their bad poetry and self-pitying.

And just as serendipitously as people intersect, they disappear. The Woman in the Blonde Wig disappears into the night, a freeze frame capturing a split second of her without her wig and her true identity. Faye stands up Cop 663, the swirl of colors becoming an oil painting as she disappears, only to return as a flight attendant, of all things – having made it to California of California Dreamin’ fame. The two reunite and perhaps, perhaps, the city has had a hand in curing loneliness.

Would these people have met had it not been for what a city can be, how it can push people together just as easily as it can obscure them? Hard to say, of course, but if you believe the city is a character - as it is almost certainly is here - then their fate is maybe not totally in their hands. It’s the unseen, alive presence of the urban world that has set their lives in motion.

Wong Kar-wai captures a city perhaps better than anyone else. You feel the sweat, the grime, the physicality of the place. The fluorescent lights of the soda shops, the interplay of shadow and light from buildings and cloths draped across alleys. The city is a character in many films but it is, arguably, the star of Chungking Express.

Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964)

QFS No. 161 - Yes, Umbrellas of Cherbourg (`964) may not seem like a holiday classic. But it very well could be!

QFS No. 161 - The invitation for December 18, 2024

What kind of sicko would watch a French film from the 1960s during this time of the year when there is an entire subgenre of “Christmas movies” available at our fingertips?

You, is the answer. And me, more accurately.

Yes, Umbrellas of Cherbourg may not seem like a holiday classic. But it very well could be! It appears that way on at least one site I’ve consulted, and nevertheless I’ve had this movie on my radar for a long time. For starters, the visuals have inspired a legion of filmmakers, including most recently Greta Gerwig who cites it as one of her inspirations for the visual style and color palate of Barbie (2023). And it stars the great Catherine Deneuve in this unique musical from France.

Everything I’ve heard about the film is highly positive, including its inclusion on the BFI Greatest Films List where it’s 122nd Greatest Film of All Time, tied with There Will Be Blood (2007), The Matrix (1999), The Color of Pomegranates (1968, QFS No. 130), Johnny Guitar (1954) and Only Angels Have Wings (1939). Quite a logjam at 122nd! (Also, just after The Thing, 1982, QFS No. 115.

Look, I know – French film, and a musical no less! Have you gone mad? The answer is – have you seen 2024? It’s made us all a little mad. My dislike of musicals aside, I’ve heard great things about Umbrellas of Cherbourg and very much looking forward to seeing it on this, the 60th Anniversary of the film’s release!

So do join me in watching this, our final film of 2024 and discuss below!

Reactions and Analyses:

Early on in Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), one of Guy Foucher’s (Nino Castelnuovo) co-workers in the auto mechanic shop finds out that Guy is going to see the opera Carmen and can’t stay late at work or join them at the game. One of the co-workers says, “I don’t like operas. Movies are better.”

The great irony, of course, is that the co-worker is singing this line of dialogue, just as everyone is singing every line in this movie. Opera, being the other medium where singing from start to finish is what we expect. Here, of course, in Umbrellas of Cherbourg, everyone is also singing throughout – the throw-away line feels like director Jacques Demy’s fun inside joke to us, the audience, watching this film that’s more opera that movie.

The more traditional musicals, by and large, rely on a certain artifice of course and the musical numbers puncture the realism that movies attempt replicate on the screen. But with a musical, you know you’re watching something not-quite reality and any time a musical number begins it’s a necessary interruption from the narrative norm. Take an animated Disney film or a standard Hindi/Bollywood film – the narrative usually continues forward until the next musical number where you’re reminded you’re watching a musical.

In Umbrellas of Cherbourg, the music is constant and all the mundane aspects of life are sung. It was as if I was watching a movie in a foreign language (beyond just French) in which that’s just they speak in Cherbourg. I found myself giving in to the singing and in a way didn’t even realize I was watching a musical any longer. Once a film’s grammar or its style is established – could be fantastical or documentary style or neorealist – it’s easy to disappear into it. For me, I find myself as a viewer less able to disappear into a standard musical because of the puncturing of reality the musical numbers take.

But I didn’t experience that sensation in Umbrellas of Cherbourg – I was swept away into its world and could accept that even the mailman will sing his only line, saying he has a letter for Genevieve (Catherine Deneuve) or that the gas station attendant will sing when he asks whether she wants diesel or regular. The language was set and the grammar established and the rules were clear – everyone sings.

Our group also got to wondering: Is Umbrellas of Cherbourg the greatest wallpapered movie of all time? If not, what could be No. 1? The use of color in Umbrellas of Cherbourg, of course, have long been celebrated. But despite the vibrancy of the sets and costumes, the film is not candy and saccharine, which is what I had anticipated. The film contains teenage pregnancy out of wedlock, discussions about what to do about it, a depressed man visiting a brothel and hiring a prostitute, a dying aunt, going off to war, and a gas station of all places as a climactic romantic scene. Though it might look like it, this is not candy.

And the filmmaking isn’t candy either. There are no dance numbers, no nods to the audience except for that clever line about the opera at the beginning of the film. There’s nothing cutesy about the relationships - Genevieve’s mother (Anne Vernon) consistently berates her and is more concerned about what others will think about her pregnant teen instead of her actual well being. When Genevieve decides to marry Roland (Marc Michel) in order to avoid financial ruin, that montage is a prime example of how to advance time and story simultaneously. And in that advancing of time we get the hasty nature of the relationship - it’s full-steam ahead and Demy shows us how quickly events unfold from decision to marriage.

And this shot of Guy leaving for war and pulling away from Genevieve is utterly stunning and evocative - the music crescendos and Genevieve gets smaller and smaller in the distance and eventually out of Guy’s life altogether. It’s utterly perfect.

With the deft filmmaking and use of color throughout to enhance the storytelling, it's no wonder Umbrellas of Cherbourg have inspired contemporary filmmakers, most notably the costumes and set design utilized by Greta Gerwig for Barbie (2023) and much of the story, the color and the climactic sequences of Damien Chazelle’s La La Land (2016). But several of us in the group suspected that Spike Lee perhaps took some inspiration from Demy’s film as well. Guy has been drafted and about to leave for war in which he and Genevieve are in the alley in embrace. They’re moving but not walking, and the wall moves behind them as they sort of glide along – it’s one of the only non-realistic (other than the singing) moments in the film, so our attention is brought to it immediately.

Spike Lee uses this technique of putting the actor or actors and camera on a moving platform so often that it’s hard to list all the films he deploys this shot - most recently seen in BlacKkKlansman (2018, QFS No. 83). Demy is not the first to do this of course, but throw in the use of big bold colors on the set design and decoration along with the melodrama of the story, and it’s not too much of a stretch to believe that Umbrellas of Cherbourg had an impact on Do the Right Thing (1989) (especially given Lee’s admiration for great cinema that came before him).

The film has endured with filmmakers in many ways similar to the way Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet has endured over the years, I’d argue. Not on the historic magnitude as Shakespeare, of course, but Demy’s story about young impetuous love, missed opportunities, and bittersweet tragedy would be familiar to The Bard. Shakespearean melodrama elements all right there, tragic and beautiful at the same time. In the end, Guy and Genevieve never manage to build a life together and Guy is her daughter’s biological father – but they will never meet. And Roland has chosen to love Genevieve and marry her despite knowing she was pregnant at the time. We never see Roland again on screen but we see that Genevieve is now the wealthy wife and seemingly happy – though now, draped in brown fur as the wealthy do and not awash in the colors of her pre-motherhood youth.

And the final shot – perhaps arguably the most cinematic conclusion you can have at a gas station – suggests that although life didn’t work out as planned for either Guy or Genevieve, they have found a life that has made them happy, or at least content. It’s not the ending you expect of a standard musical, but if anything from the movie is clear, Umbrellas of Cherbourg is anything but standard.

Princess Mononoke (1997)

QFS No. 157 - We are all long overdue to be taken away to a different land. At least for a couple of hours. And there’s perhaps no one better suited to take us elsewhere than the Japanese master of animation, Hayao Miyazaki.

QFS No. 157 - The invitation for November 20, 2024

We are all long overdue to be taken away to a different land. At least for a couple of hours.* And there’s perhaps no one better suited to take us elsewhere than the Japanese master of animation, Hayao Miyazaki. We have technically never selected a Miyazaki directed film, but his Studio Ghibli produced Grave of the Fireflies (1988, QFS No. 23), which was the first animated film we selected to watch for Quarantine Film Society.** Studio Ghibli films’ streaming distribution opened up more widely recently, which is an exciting development and will make it easier to see all of these great Miyazaki masterpieces.

Princess Mononoke is high on that list. In 1997, there was not yet an Academy Award for animated feature. Had there been, Princess Mononoke would’ve been the odds-on favorite to win that year. Disney, who dominates the category, had the above average Hercules (1997) and Anastasia (1997) – not classics, which is how Princess Mononoke is often described.

Fast forward a few years when the Oscar category was created, and Miyazaki takes home the statuette for Spirited Away (2001), a truly magnificent film that I’d rank among the greatest animated movies of all time. And just last year, at 80-years old, Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron (2023) won the top animated prize again. My Neighbor Totoro (1988) remains a favorite around the world. Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (1984) are among the titles that are celebrated by anime fans and others alike – and there are dozens more.

Miyazaki’s storytelling contains magic on par with Disney’s, but I’d argue even more so with stories that are layered and contain even deeper explorations of character and the soul. His stories take on complex emotions and never pander to the audience – which we definitely saw in the post-war tale of Grave of the Fireflies. Though animation as a medium is often aimed at children, his stories cater to adults as well, often with haunting imagery and disturbing sequences. Miyazaki has elevated the medium and the genre and has made an indelible mark on the film industry as a whole.

I’m very much looking forward to finally seeing Princess Mononoke. Disappear into Miyazaki’s world for a couple hours and join us to discuss here!

*Ideally, longer.

**Flee (2021, QFS No. 69) is the only other animated film we’ve selected due to a long-standing bias among some members of our QFS Council of Excellence (QFSCOE).

Reactions and Analyses:

At the end of Princess Mononoke, the victor is nature. The enraged, decapitated Forest Spirit has just decimated Iron Town, the human-made walled outpost that’s been mining ore and decimating the forest in its path. Iron Town’s ruler Lady Eboshi (voiced by Minnie Driver in the English dubbed version) has had her arm bitten off by the wolf goddess Moro (Gillian Anderson).

But San (the titular Princess Mononoke, voiced by Claire Danes) and the story’s main protagonist Ashitaka (Billy Crudup) have retrieved the head and returned it to the Forest Spirit, healing it and the cataclysm has ended. In the spirit’s wake, the Iron Town is destroyed - but it’s not the end of the story. Instead, over all the destruction, sprouts being to spring and grass grows and nature reclaims the land. In the end, nature is victorious.

If there’s a central idea of Princess Mononoke - and there are several, some that were a little harder to discern for us in the QFS discussion group - it is this: nature will endure and prevail, if we help it. If we, as humans, can live in harmony with it, symbiotically.

It’s no surprise that several movies including Avatar (2009) are influenced by Hayao Miyazaki’s epic story in Princess Mononoke - from both a story perspective and also visually. But what sets Princess Mononoke apart from Western fare including Avatar is that neither humans nor nature are all entirely good or entirely bad.

Take Iron Town. The town is clearly destroying the land and exploiting its resources. Lady Eboshi is an unrepentant capitalist hell bent on ruling the world. (In fact, she holds up a newly created rifle saying that it’s a weapon that you can rule the world with.) But even she has more layers than that - she is not the villain of the film, to the extent that there is a villain of the film.

In fact, it’s quite the opposite - she is extremely benevolent. We learn she took women out from working in brothels and gave them dignity and power - but also putting them to work in the bellows of the iron works. She’s taken in lepers who were cast out from society - but also has given the task of making weapons for Lady Eboshi’s growing empire.

In this way, Miyazaki is pointing out something that we see every day in real life. Large corporations whose business is tearing up the Earth for resources to fuel modern economy and industry, claim that they are benevolent. Sure we’re extracting fossil fuels and poisoning the atmosphere, but we’re also providing jobs, education, and look how many renewable energy projects we’re funding!

All of the characters are complex in this way. Even nature isn’t all good either. The wolves are particularly nasty, threating to bite off Ashitaka’s head at any given moment. The boars in particular are brutish, headstrong and unwilling to compromise. It’s their inability to let go of hatred that brings on the demon - or something like that.

Which is one aspect of the film we all found confusing - the rules and the mythology. Narratively speaking, the first half of the film or so is breathtaking in its scope and clear in its vision of a journey for Ashitaka to find a cure for his arm and “to see with eyes unclouded by hate.” But in the second half, Ashitaka encounters humans at war - samurai versus Iron Town, messy allegiances, even in the forest with the animals including the apes. And in the end, after all is said and done, Lady Eboshi and the conniving Jigo (with strangely aloof voicing by Billy Bob Thornton) receive no comeuppance. Eboshi does have an arm cut off, but even when nature is restored there is nothing to suggest, necessarily, that she’s going to change her tune and live in more harmony with nature. And Jigo - whose mission was to decapitate the Forest Spirit at the Emperor’s behest - survives and shrugs it all off.

Perhaps this, too, is Miyazaki’s point several in our group contended - that these people continue to live among us. People who would live in discord with nature, with ill intentions who are only looking out for themselves. So this balance between nature and life will continue. And it’s also true that we, as American filmmakers and viewers, expect a narrative arc or change in a character. But in the East, perhaps that’s less necessary or expected - even in an animated film. After all, Ashitaka doesn’t really change at all, if you consider him the protagonist - he begins righteous and stays righteous. If anything, he’s trying to have everyone fight against resorting to anger and destruction and he loves the people of Iron Town but also Princess Mononoke and the denizens of the forest. San (Princess Mononoke) in fact still distrusts humans and her human self and doesn’t actually end up with Ashitaka.

Despite this lack of a narrative arc we’re hoping for as Western audience members, Miyazaki is painting a picture of there is no good and no evil. Nature itself destroys and brings to life. The Forest Spirit saves Ashitaka but also kills plants and destroys the countryside, just as life springs forth beneath its feet.

Miyazaki has mastered the animated film. But what he’s done to elevate it is that he manages to make the fantastical feel realistic. He manages to make the world three-dimensional, as if it’s there’s a camera on that hillside filming the wolves as they carry the masked San/Princess Mononoke, dodging real rifle shots. It’s a truly remarkable experience to disappear into a Miyazaki world.

But the world he’s creating, especially here in Princess Mononoke is a mirror to our world - a plea for what he hopes is ultimately balance in a world living in the absence of that balance, teetering on mutual destruction.

Near the end of the film, Princess Mononoke/San says, “Even if all the trees grow back, it won't be his forest anymore. The Forest Spirit is dead.”

Ashitaka replies, “Never. He is life itself. He isn't dead, San. He is here with us now, telling us, it's time for both of us to live.”

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974)

QFS No. 154 - Rainer Werner Fassbinder is one of those filmmakers whose work I, as film snob and student of film, should have seen. But instead, I pretend I know about Fassbinder – of course I do. I went to film school, you see.

QFS No. 154 - The invitation for October 9, 2024

Not to be mistaken with Ali (2001), the Michael Mann biopic about Muhammad Ali. Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, as far as I know, has very little boxing and probably even less Muhammad Ali in it. But who knows!

Rainer Werner Fassbinder is one of those filmmakers whose work I, as film snob and student of film, should have seen. But instead, I pretend I know about Fassbinder – of course I do. I went to film school, you see.

Consequently, I know very little about Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, but more than one person has recommended it to me in recent years. One institution gives this film high marks as well – specifically the British Film Institute, where it came in at No. 52 on the Greatest Films of All Time List. You’re familiar, of course, with the oft-cited/derided BFI/Sight & Sound list that comes out every decade. Well, Ali: Fear Eats the Soul is tied in 52nd I’ll have you know. Tied with (checks notes) News From Home (1976) directed by Chantal Akerman – you all know her as the director of the No. 1 Greatest Film of All Time, Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975, QFS No. 98).

Anyway, I’m looking forward to seeing my first Fassbinder film, which will be our third German film after Aguirre: The Wrath of God (1972, QFS No. 40) and Downfall (2004, QFS No. 28) – so it’s been about 112 films since our last time with the Germans. See Ali: Fear Eats the Soul and add Fassbinder to your snobby film cred as well!

Reactions and Analyses:

There’s a scene more than halfway through Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974) that feels like a fulcrum of film. Moroccan-born Ali (El Hedi ben Salem) and the older German widow Emmi (Brigitte Mira) have fallen in love, but their uncommon pairing has drawn the ire of nearly everyone they encounter. Emmi is shunned by neighbors and co-workers. Her grown children stormed out in anger, with one son Bruno (Peter Gauhe) even kicking in the screen of her TV set.

All of this Emmi accepts with grace, and feels that people, though surprised at their relationship, are eventually going to come around. She knows she’s old and people are prejudiced against people from the Arab world. But in this scene, her fortitude has run out. They’re in an outdoor café, in a plaza, surrounded by yellow chairs. Not one sits next to them, they’re in the center of their own world. All the café staff stand back and away from them, simply staring.

Emmi and Ali hold hands across the table and Emmi breaks down. She lashes out at them, at the world, for treating them this way when all they want is love. Ali tenderly strokes her hair to console her. The scene feels like a tipping point, the moment in which Emmi’s underlying belief in the ultimate goodness in people has cracked.

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul feels as if it could’ve taken place today, that it could be a contemporary story. It is a contemporary story – you can imagine these characters swapped with someone who is African American or Latinx or, well, Arab. Prejudice and racial discrimination is not unique to any one country.

What makes this film so unique, however, is that this is Germany not quite 30 years after the end of the Second World War. The references to Hitler are surprisingly casual and off-handed and suggests to me that director Rainer Werner Fassbinder is making a comment about his own country’s lingering difficulty with race and prejudice. Instead of blaming Jewish people for their ills, characters throughout blame the immigrants from Arab-speaking countries.

Emmi’s son-in-law Eugen (played by Fassbinder himself), a vile misogynist, bristles at the notion that his superior at work is Turkish. He sulks at home “sick” but clearly just lazy and drunk, demanding beers from his wife Krista (Irm Hermann), The two couple are miserable with each other, constantly insulting and clearly hate each other. Fassbinder seems to be deliberate about the juxtaposition of this scene with the previous one, which is after Ali has left Emmi’s place and the two have made love in the night. People may look down on Arabs for being “swine” and lazy, cramming in homes instead of buying their own place (according to the ladies Emmi works with), but Fassbinder forces us to see that this is untrue – just look at how miserable Eugen is and his home life with Krista. If anything, native-born Germans are the ones who are taking their good fortunate and privilege for granted.

But everything is deliberate with Fassbinder, we found. The compositions are steady still, often using doorways or the staircase to provide a frame within a frame or obstacles to our viewing. He moves the camera only when needed and with great effect to bring our attention to something in particular.

Take the opening scene. There’s beautiful, hypnotic Arabic music playing and a woman steps in from the rain into a place, drawn by the music. She’s a stranger here – the frame is still. The reverse angle, her perspective, we see everyone straight upright staring back at her. Their posture speaks volumes, as if to say something’s not right here. Then the bartender Barbara (Barbara Valentin), comes around the bar and the camera pushes in, she passes buy which creates extra dynamism in the camera move and it pushes closer to Ali, who we are introduced to here, in a way.

There are numerous instances when the camera’s movement is precise, purposeful, and helps tell the story in this way. Or lack of movement. Emmi and Ali go into an Italian restaurant (“Hitler used to go here!” is an unsettling plug for this place) after they’ve been married in court, and Fassbinder keeps his distance, playing much of the scene from another room through a doorway. It’s cold, like the reception they’re getting from the waiter as strangers in this place.

Although it had been well documented, I was previously unaware of Fassbinder’s connection with Douglas Sirk and about how he was inspired by the German ex-pat’s work in the American film industry. Sirk, who we just recently selected two films ago (Imitation of Life, 1959, QFS No. 152) mastered melodrama, but also mastered the ability to take on socially provocative subject matter. In Imitation of Life, it’s race, just as it is in Ali: Fear East the Soul. Several people over the years have pointed out that All that Heaven Allows (1955) is a direct parallel to Ali: Fear Eats the Soul – an older woman and a younger man fall in love – but Fassbinder supercharges it with race. But he does it in a way that’s even more evolved than Sirk, in my opinion.

Where Sirk does an admirable job tackling social touchpoints, specifically race in Imitation of Life in during a time where racial discrimination was high in America – Jim Crow laws still very much in effect throughout the South – Fassbinder inflects his story with another angle. Both characters are lonely. We can see the stress it inflicts on Ali as an Arab in that it actually starts to kill him. But he strives for any sort of comfort from home – couscous, for example. (Which led to this trenchant over-simplification by one in our group: “Can you make me couscous? No? I’m leaving.”)

It’s this loneliness that bring these two together. Is that enough to sustain a relationship? No, and it frays. But they come back together and there’s a sense that they truly do love each other, even though Ali is stoic and speaks in broken sentences.

If there’s a shortcoming of the film, is that Ali at times is objectified. This is possibly a comment as well by Fassbinder – he’s seen as one-dimensional if it fits someone’s needs. The woman feel his muscles, ask him for help, admire how young he is once people start to suddenly accept their relationship. Even the son comes and apologizes for breaking the television and sending a check. But even he is angling for something – he needs childcare from his mother to look after her grandkids when they need it.

So we don’t see Ali’s perspective enough, in my opinion. Had we been given a chance to see Ali speak in Arabic, for example, we wouldn’t see him as a brute as much, would see that he’s intelligent and thoughtful, perhaps, in ways that don’t come out as much when he’s struggling to speak in German. And see him comfortable in the other half of his dual identity as an Arab German.

One member in our QFS discussion group pointed out that we only see the racism and how people treat them after their married, and no other sense of their homelife. It becomes a bit too much, overly taxing, and gives us the feeling that the only thing they experience is racism. True, that’s the feeling conveyed, but if they love each other we could do with at least one or two scenes of domestic bliss. After all, we’re led to believe that they truly love each other and not that Ali is in this for some other gain or that she’s using him to stave off loneliness.

All this aside, Fassbinder’s stripped down film is somehow captivating. It’s this bare-bones feeling, this lack of cinematic tropes – which is far different than Sirk, by the way – that gives the impression of realism. Not Realism in formal sense, but a feeling that this is a very believable, realistic story that’s happening right now as we watch it unfold. And probably that’s because it is a story happening right now, every day, in many places around the world.

Godzilla Minus One (2023)

QFS No. 151 - This is the first kaiju film selected by Quarantine Film Society. Kaiju, of course, is the film subgenre in which giant monsters destroy things. I think it’s amazing that what seems like a very limited type of film has a named subgenre, but this is where I’m wrong. There are tons of these movies and television shows varying in quality in the 70 years since Godzilla (1954) came out from Japan. I’m certainly no expert on these films, but I do enjoy a good giant animal picture now and again.

QFS No. 151 - The invitation for September 4, 2024

Godzilla Minus One (2023) is the first kaiju film selected by Quarantine Film Society. Kaiju, of course, is the film subgenre in which giant monsters destroy things. I think it’s amazing that what seems like a very limited type of film has a named subgenre, but this is where I’m wrong. There are tons of these movies and television shows varying in quality in the 70 years since Godzilla (1954) came out from Japan. I’m certainly no expert on these films, but I do enjoy a good giant animal picture now and again.

Godzilla Minus One created quite a buzz last year and I really wanted to see it. I’ve heard good things about it from a filmmaking and storytelling perspective, but also in the visual and special effects. If I’m not mistaken, they had a very slim VFX team compared to say big studio movies. And yet, they took home the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, beating out a Marvel film, a Mission: Impossible film and Ridley Scott who is no stranger to Visual Effects. The first foreign language film to win the Visual Effects Oscar, which is cool.

Speaking of, this will be our fifth selection from Japan but our first Japanese film from this century. So curl with Godzilla Minus One and watch a giant lizard break things! (#spoiler) Join us next week for Godzilla Minus One.

Reactions and Analyses:

Is Godzilla’s destruction purposeful? Does he (it, she, they) know what he’s destroying? Is it intentional? Or is the destruction indiscriminate?

That was one of my main questions for the QFS discussion group and several were curious about this as well. And perhaps, for a mega-superfan of kaiju films, this is a question that’s very basic. But for someone like myself, it seemed an important question.

Perhaps the reason why I’m curious about this is that I’m not sure how to feel towards Godzilla. In some sense, if the destruction is unintentional, there’s a bit of sympathy one can feel towards the creature. It doesn’t know what it’s doing, it’s primal and a production of human tampering with nature – then it’s almost justified in its actions. A force of nature. After all, you can’t be angry with the actions of a hurricane or a volcano because it’s something unlocked by the Earth.

But if Godzilla is an avenging god, wreaking havoc on a populace already suffering from the toll of devastating global war – then, it gets a little complicated. Godzilla, portrayed for seventy years on the big and small screens, appears in Godzilla Minus One as being fueled - or at least “embiggened” - by human’s insatiable need for bigger, larger and more destructive weapons. A scene, almost a cutaway scene, depicts the US dropping experimental nuclear bombs on the Bikini Atoll – with an insert shot of an underwater monstrous eye opening and powering up. The implication is this is what humans hath wrought. Nuclear war and self-annihilation.

Or as metaphor, a giant uncontrollable lizard getting larger and larger as it destroys more and more. A stand-in for the arms race writ large.

All Godzilla films are metaphoric and perhaps cautionary, from the original 1954 version to this one in 2023, borne of post-war Japan where nuclear annihilation was not theoretical but actual. It’s astonishing to realize that only nine short years after World War II and on the heels of the nuclear bombs wiping out Nagasaki and Hiroshima, that Toho Studios would make a film about a creature that was destroying Japanese cities. I even had this feeling while watching the 2023 iteration, that these poor people had suffered enough from fire bombings and nuclear weapons – isn’t it a bit too much to also subject them to a giant destructive lizard?

Perhaps this is where cultural tastes and takes diverge between the US and Japan, which came up in our conversation. It’s easy to imagine that if the roles were reversed, that US filmmakers would very much make a film of giant monsters attacking Japan or Germany – their enemies in that war – as opposed to attaching its own populace on the shores of the Untied States . We found ourselves pondering what would’ve happened if Japanese filmmakers did indeed decide to make a 1954 film of Godzilla attacking the US, a revenge fantasy film in the way that would make the likes of a young Quentin Tarantino proud. Retribution through art is something we’ve seen before, but the Japanese have resisted that and instead turn inward with the Godzilla films.

And especially in Godzilla Minus One. Shikishima (Ryunosuke Kamiki) was a naval flyer in the war but when we discover him, he’s abandoned his duty as a kamikaze pilot honor bound to die in a suicide attack against the Allies. Although this is shameful, culturally, in 2024 looking back the filmmakers turn this around and seem to say – yes, that was your duty then, but now we need to live and build our nation. And by ejecting just before he flies into Godzilla’s mouth with his bomb-laden plane, Shikishima saves the day, lives honorably, and lives on – even rewarded by discovering that Noriko (Minami Hamabe) is still alive. So living is worth living for, you see.

The nationalistic pride in Godzilla Minus One evoked another recent film we’ve screened from another part of Asia - RRR (2022, QFS No. 86). In S.S. Rajamouli’s revisionist period piece, India is a place that had physical might and used violence and warfare to overthrow British rulers. Never mind the fact that this never happened and India is well known for its nonviolent moral and intellectual revolution that truly changed the world (as portrayed in Gandhi, 1982, QFS No. 100) – the India of 2022 is trying to assert a new world dominance. One that shows its military, technological and physical might as opposed to its intellectual and moral one from the past. RRR is a virulently nationalistic work of fiction that seeks to scrub that past and recast India as a mighty nation, ready to do battle. I, for one, found this appalling and will discuss further in the RRR QFS essay that remains TBW.

And yet, there’s a parallel we found in our discussion with Godzilla Minus One. Japan was demilitarized after World War II and there was a sentiment that they might prefer to live that way, to build their society and give up their imperialistic past. In 2024, the world is a vastly different place. With a resurgent and belligerent China at their doorstep, is Godzilla Minus One recasting Japan’s past, to show that they have might in numbers and a national pride? And that this means their love of the Japanese country fuels their current military force for good and will keep the Chinese at bay? The former soldiers in Godzilla Minus One fight not because it’s their duty as soldiers, but it is their collective duty to build a nation of people, assembling a “civilian” navy to fight an enemy at their shores. One can interpret that this is all proxy for regional domination and moral superiority over a foe, even if it’s not overt. (Though, to me and others in the group who brought this up, it feels overt.)

But while the film does have this national pride coursing through, there is ample criticism of the Japanese government. The former admiral Kenji Noda (Hidetaka Yoshioka) says:

Come to think of it this country has treated life far too cheaply. Poorly armored tanks. Poor supply chains resulting in half of all deaths from starvation and disease. Fighter planes built without ejection seats and finally, kamikaze and suicide attacks. That's why this time I'd take pride in a citizen led effort that sacrifices no lives at all! This next battle is not one waged to the death, but a battle to live for the future.

There you see this pride, but also damnation of nation’s leadership. It’s a fine line for the filmmakers to walk and they do so pretty well. Which got us to thinking – this is about as good as you can make this type of film, isn’t? The filmmakers balance politics, human drama, and action in a film about a giant lizard destroying everything in its path. There’s ample metaphor, there are emotional stakes – it all comes together in an science fiction film.

I does feel, however, of the scant Japanese Godzilla films I’ve seen, this one has taken some of the worst of American action film schlock and absorbed it, much the way Godzilla absorbs ammunition rounds. There’s the extremely cheesy lines, the overwrought emotions and overly convenient storytelling. Unfortunately, Noriko is saddled with several of these – Is your war finally over? As her first line to Shikishima when they reunite at the end feels straight out of the worst Jerry Bruckheimer/Michael Bay collaboration. Is that … Godzilla? Is one of the more useless expressions of dialogue you’ll find in a movie but it did make me laugh out loud (unintended comedy laughter is still laughter I guess). And of course, Noriko somehow survives Godzilla’s energy breath blast giving us the happy American-style (or Bollywood-style) ending we’ve come to expect with a massive film like this. Not to mention the somewhat predictable climax, where Shikishima ejects and survives as well.

Are these flaws or features? Any way you slice it, to make a film about an indiscriminate killing force that destroys on a large scale, is no small feat (pun intend… small feet… never mind). But to make it memorable, you have to make it about people, not about the lizard. And even if their emotions are not totally believable, they sure are more believable than a giant monster reigning terror across a nation. The bringing together of both make for what might just be the apex in kaiju – specifically Godzilla – movie making.

Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959)

QFS No. 147 - Kaagaz Ke Phool – which translates to “Paper Flowers” – is known as one of the great films from the Golden Age of Hindi Cinema.

QFS No. 147 - The invitation for July 17, 2024

Let’s complete another chapter in our on-going Introduction to Indian Cinema 101!

Guru Dutt is one of the unheralded filmmakers from India. “Unheralded” is in quotes because he’s quite ... heralded? ... in India. Though recognized as a great in his own country, he never achieved international acclaim in his lifetime the way that Satyajit Ray did, for example. For me, I was first introduced to Dutt’s work about twenty years ago when Time magazine’s legendary film critic Richard Schickel listed Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa (1957) as one of the 100 greatest films ever made. Pyaasa is a classic that’s moving and also has the unofficial Hindi film mandated musical numbers. But the musical numbers in Pyaasa are not superfluous – they serve the story, bringing poetry to life and enhancing the story. His follow-up Kaagaz Ke Phool – which translates to “Paper Flowers” – is known as one of the great films from the Golden Age of Hindi Cinema.

Now is a good time to recap our course materials for Introduction to Indian Cinema. Here are the films the QFS has selected (in chronological order):

1. Apur Sansar (World of Apu, 1959, QFS No. 16) – part of Ray’s “Apu Trilogy” and the origin point of Indian independent and art cinema.

2. Sholay (1975, QFS No. 62) – a glimpse of a big mainstream Indian movie during an era when such films were uninfluenced by global cinema. Also, our first viewing of Amitabh Bachchan, the most famous movie star in the world.

3. Dil Se.. (1998, QFS No. 32) – where we could see the influence of MTV’s arrival into South Asia, in which a movie produced standalone music numbers that felt separate from the main film. Also showcasing the ascension of Shah Rukh Khan as global heartthrob and second most famous movie star in the world.

4. 3 Idiots (2006, QFS No. 118) – closer to present-day Hindi filmmaking ripe with broad humor, earnestness, and adapted from a popular contemporary novel.

5. RRR (2022, QFS No. 86) – example of a regional language film (Telugu) that exploded into the world consciousness, showcasing modern filmmaking India style.

That’s not bad for a four-year, unstructured and barely planned course into the filmmaking of the largest movie producing country on earth!

You’ll notice in the above list that Apur Sansar and this week’s film are both from 1959. But they represent completely different branches of Indian cinema. Apur Sansar is from Bengal and not considered part of the national films of India (which we now call “Bollywood” but is really known as “Hindi Films” you may recall from our previous lessons). Ray’s Apu Trilogy was more popular abroad than in his own country, where he produced and directed from outside of the national movie industry. He is the first known filmmaker to make a successful film outside the traditional Indian movie studio. The independent scene in India remained very thin for the next 50 years, but the Apu Trilogy is where it begins.

Whereas Guru Dutt was already a Hindi film star known all over India by 1959. While Ray toiled as what we would now call an independent filmmaker, Dutt was a studio filmmaker. He operated within the Hindi film ecosystem, casting stars (including himself) but told deeply personal stories in between the songs and the dances. Kaagaz Ke Phool represents our QFS selection from the Golden Age of Hindi Cinema.

And while Dutt made commercially viable films, his personal life was marred by strife. Perhaps the melancholic storytelling he showcased on the screen came from his world at home. Tragically, he died before he turned 40 possibly from an accidental overdose or possibly, he committed suicide. This is his final film as a director (he acted in eight or so more after this) and though his life was short, he left behind an incredibly impressive body of work as a filmmaker. Dutt remains a revered artistic luminary in India and in film circles – both Pyaasa and Kaagaz Ke Phool appear on “Greatest” lists in India and internationally, including the latter once appearing on the BFI/Sight and Sound Greatest Films of All Time list in 2002. I believe India also issued a stamp in his honor as well.

So join us in watching Kaagaz Ke Phool – the first Indian film in Cinemascope! – and we’ll discuss in about two weeks.

Reactions and Analyses:

In Guru Dutt’s Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959), there are a few scenes that concern horses and take place at a horse racing track. For a movie set primarily in the world of the 1950s Hindi cinema industry and very little to do with horses, this feels superfluous. And, for the most part it is superfluous – it doesn’t have much to do with the main storyline. But it pays off in a way later on thematically.

Rocky (Johnny Walker), who owns and bets on horses, reveals late in the film that one of his prized horses had to be shot and killed because it broke its leg and couldn’t race any more. Not much good now, but the horse had made me millions before, Rocky says. So we had to shoot the horse, he reveals, almost as an afterthought.

At the same point in the film, the protagonist Suresh Sinha (played by Dutt himself), a director who was successful and made many hits for his studio, has hit rock bottom. Drinking, depression, and abject loneliness left him a shell of a man – unemployable and forgotten. Not much good now, but this director made them all millions before. Suresh is not being put out of his misery in the manner of a horse, but perhaps he should be?

The metaphor is clear, and it’s brutal. Fame is fleeting and also no matter what you’ve done before or how successful you once were, you end up dead and alone. Which is what happens to Suresh, who, in what is the most savage scene of the film, dies quietly on the soundstage in which he had once flourished. The morning crew comes and finds him dead in a director’s chair, but the producer doesn’t care. He just wants the body moved (“what, you’ve never seen a dead body before?” he shouts) because the show must go on. The camera rises up to the heavens in a wide shot as light pours into the stage from the outside as Suresh’s lifeless body, small in the frame, is carried off.

It’s an incredibly cynical portrayal (and likely accurate from Dutt’s experience) of a ruthless world, specifically the movie industry. The fact that this is in a 1959 Hindi film – a film industry very well known for cheery, elevated and escapist fare – makes it even more surprising. What’s less surprising, perhaps, is that audiences at the time weren’t too keen on seeing Kaagaz Ke Phool, a notorious flop, only to be rediscovered and cherished now. Perhaps that says more about the times we currently live in than the quality of the film itself.

And to that quality – Kaagaz Ke Phool is a stunning masterwork of directing. Someone in our QFS group pointed out that not only do the shot selections evoke Orson Welles – deep focus, wide frames, low angles utilizing Cinemascope lenses for the first time in India – but Guru Dutt himself looks a lot like a young Welles himself. Both were prodigy actor-directors, both fought inner demons. And while Welles lived with his for a long lifetime in which he fought to regain the fame and power he had when Citizen Kane (1941) reached its ascendancy, Dutt’s demons proved too much for him, and instead died before he was 40. Dutt left behind a legacy of classics and a the tragic feeling that we were deprived of more great and meaningful films to fortify the Indian film industry.

It's easy to find parallels between Suresh in Kaagaz Ke Phool to Dutt’s own life. But beyond that, the film is a masterclass in portraying loneliness. Dutt with VK Murthy – one of India’s legendary cinematographers – has Suresh move between shadows and silhouettes, throwing the focus on the background and trusting the audience with extracting meaning from his imagery and juxtaposition of characters in the frame.

Perhaps the most evocative scene comes about halfway through the film. Suresh has discovered and clearly has fallen in love with the luminous Shanthi (Waheeda Rehman), a non-actor who reluctantly becomes a star in his movies. He’s still technically married to Veena (Veena Kumari) but has fallen in love with Shanthi, and Shanthi, has definitely fallen for him. But they can never be together. To portray this visually, Dutt has music playing between the two characters on a darkened soundstage, featuring the now-legendary Mohammed Rafi song “Waqt Ne Kiya Haseen Sitam” which roughly means “What a beautiful injustice time has done (to us).” There are only shafts of light in an otherwise dark space with each going in and out of shadows and light. It begins with his wife Veena in the scene (possibly imagined), looking distraught as the camera pushes in to a close up, cut with a similar closeup of Suresh as well.