Out of the Past (1947)

QFS No. 172- You can’t possibly go wrong with two of the greatest faces and square jaws in movie history – Robert Mitchum and Kirk Douglas.

QFS No. 172 - The invitation for April 9, 2025

I can’t quite remember how this movie made it on to my radar, but I have heard good things. And you can’t possibly go wrong with two of the greatest faces and square jaws in movie history – Robert Mitchum and Kirk Douglas. What else do I know about this movie? It’s a 1940s noir thriller and so it probably contains a dame, low key jazz saxophone or horn playing, fog, copious amounts of smoking, inky night scenes, and at least one trench coat. (I cheated on that last one and saw a still from the picture.)

Join us in discussing Out of the Past!

Reactions and Analyses:

Movies, especially ones with twisty noir-like plots, thrive when they contain moments that make the audience gasp. They reflect the filmmaker’s ability to keep the viewer guessing, to fill the story with surprises and the unexpected, which is what give a story it’s life and vibrancy.

Out of the Past (1947) had at least one if not more such gasp-inducing moments. The scene in question happens about half way through the film. We learn in a long-narrated flashback that Jeff (Robert Mitchum) had fallen in love with the woman he was supposed to track down, mobster Whit Sterling’s (Kirk Douglas) erstwhile girlfriend Kathie (Jane Greer), who had fled after shooting Whit and stole $40,000 from him. Jeff and Kathie, now lovers, go on the run from Acapulco back to California but were eventually tracked down by Jeff’s ex-partner Jack Fisher (Steve Brodie) now working for Whit. Kathie shoots and kills the henchman at their mountain cabin hideaway and flees, leaving Jeff alone knowing that the story of Kathie taking the money from Whit is true, but also now alone, abandoned by his lover, forced to bury the body.

We haven’t gotten to the part that induced gasps. This entire portion of Jeff’s backstory is told through flashback, narrated by Jeff to his new lover Ann (Virginia Huston), an innocent small-town girl in Bridgeport, Calif. where Jeff has presumably attempted to lead a quiet life running a gas station. At this point in the story, Jeff has been met by one of Whit’s goons Joe Stefanos (Paul Valentine) who drove through this town on a whim and serendipitously saw Jeff’s name on the gas station. He more or less orders Jeff to go see Whit in Lake Tahoe.

At this point in the story, we don’t know whether Whit is aware that Jeff ran away with Kathie or did he believe that Jeff simply not find Kathie and also then never showed up to collect the rest of his paycheck. Jeff believes either Whit doesn’t know about his relationship with the ganster’s ex-girlfriend or Whit is upset that Jeff skedaddled. Either way, Jeff goes to Whit to clear things up and get on with his life with Ann.

He's brought into Whit’s beautiful lakeside estate and Whit is all charm, no real hint that he’s upset with Jeff at all. In fact, he wants to hire Jeff again. Which is unusual – so this is probably all a setup to something terrible or violent to happen to him.

And in a way it is – they sit down for a fancy lunch and who shows up? Kathie. The woman who tried to kill Whit, ran away, fell in love with the man who was supposed to bring her in, Jeff (or so we thought!), who then shot and killed a man, and ran away from Jeff. She came back to Whit? Why?!

It’s such a terrific moment in the film, a true surprise – at least for me, where I let out an unexpected gasp. From our discussion, several members of our QFS group did the same.

The plot, twisting and turning throughout, is what makes this and other noir films compelling. What elevates the genre is when the film says something about the human condition – greed, betrayal, love. Love features at the center of these twists. Does Kathie love either of the men or is she playing them? Who does she really love? She seems sincere in her love for Jeff but left him once and can she be trusted now when she says she had no choice but to return to Whit? After all, she lied about the stolen money. And does Jeff love the passionate Kathie or is her true love the innocent Ann?

In the end, Kathie reveals her true self as does Jeff. Jeff plans on turning her in and they barrel towards the authorities. Kathie, calls Jeff a dirty rat and swerves the car as the bullets rain down upon them, killing them both. Ann, in the final moments of the film, asks the mute teenager at the gas station attendant and Jeff’s friend (Dickie Moore) if Jeff was planning on leaving with Kathie or turning him in, and he signals that they were going to run away - which is a kind lie. It feels like his intention was to turn Kathie in and return to Ann in the small town, but the kid spared Ann the heartbreak of a lost lover.

The twisting nature of the story, allows for the various plot holes and logic gaps to be forgiven or not even noticed until later. For example, what are the chances that Whit ends up in Lake Tahoe, not but an hour or so from Bridgeport where Jeff is hiding away with a new lift? To where did Jeff send the all-important tax documents that end up being not important at all? Is it possible to kill someone like that with a fishing pole?

All of this becomes secondary to the Jacques Tourneur captivatingly efficient storytelling, the terrific cast, and the utterly perfect whip-bang dialogue found in the best of noir. The lines come so quickly and with such percussive ease that it’s hard to gather them all in. Here’s just one of many classics, when Whit has found Jeff and “invited” him to his place in Lake Tahoe before the reveal that Kathie’s returned. He’s about to blackmail Jeff into hiring him again.

Whit: Well, you told me about your business. Mine is a little more precarious and I earn considerably more.

Jeff: So I've heard.

Whit: So has the government.

Jeff: Well, this may sound ridiculous, but you could pay 'em.

Whit: Oh, that would be against my nature.

All of this makes for just the type of great noir – the kind of twisty, fun, compelling movie - you can just wrap yourself in and permit all the plot holes and logic leaps to just fade into the background. Jeff, for all of Mitchum’s hard-boiled square-jawed machismo, never once shoots or kills anyone in the film. The bodies all fall around him – literally, as Joe is felled by a fishing pole – with Kathie having by far the highest body count.

Trench coats, fasting-talking, femme fatales, and a truly fantastic amount of smoking makes for the perfect noir mood in any picture. But what makes it endure and why we should continue to watch Out of the Past are the moments of the unexpected, the turns in the story that keep you guessing and maintains the joy of watching a film that knows how to entertain.

The Philadelphia Story (1940)

QFS No. 142 - Let’s curl up with a classic Hollywood movie, and The Philadelphia Story (1940) is about as classic as it comes. Jimmy Stewart? Check. Cary Grant?! Check. Katherine Hepburn?!? Check. The great George Cukor at the helm?!?! Check and mate.

QFS No. 142 - The invitation for May 29, 2024

Time to curl up with a classic Hollywood movie. And The Philadelphia Story is about as classic as it comes. Jimmy Stewart? Check. Cary Grant?! Check. Katherine Hepburn?!? Check. The great George Cukor at the helm?!?! Check and mate.

I have never seen this film, which is a strange blind spot. The Philadelphia Story frequently comes up as one of the films of the era that has endured the test of time so I don’t have any explanation as to how I missed this in my viewing history.

George Cukor – you might recall from the QFS email about Gaslight (1944, QFS No. 106) that you likely have printed out and framed like you do with all of these – is one of the great workhorse elite Hollywood filmmakers of the day, eventually winning an Academy Award for 1964’s My Fair Lady. So you know it’s going to be a solid film even if you hadn’t already knew about it.

So join me in seeing the iconic performers in the classic The Philadelphia Story and then join us in discussing it!

Reactions and Analyses:

Do you need much of a plot if you have legendary actors and great dialogue? That question, or some version of that, dominated our discussion about The Philadelphia Story (1940). Comedy sometimes cannot transcend eras, but The Philadelphia Story is one of those films that continues to endure.

And why? This is not a cynical or facetious question – but what is it in a comedy that is funny more than 80 years ago that remains funny today? Physical comedy and slapstick can last beyond the time in which it was created – our December screening of the Marx Brothers’ A Night at the Opera (1935, QFS No. 132) illustrated that for us. But George Cukor’s comedy has really none of that physical comedy. And yet, throughout the film the dialogue and the performances are genuinely funny.

At the same time, the plot of The Philadelphia Story is an afterthought. That’s not to say it’s devoid of one – it’s nominally about a wealthy bride (Katharine Hepburn as Tracy Samantha Lord) on her wedding weekend with the wedding coming up. So we have a timeframe, a clicking clock. Throw in a plot to infiltrate this high society with a “secret” photographer (Ruth Hussey as Liz Imbrie) and journalist (Jimmy Stewart as Mike Connor) writing a story for a gossip magazine – all facilitated by the woman’s ex-husband C.K. Dexter Haven (Cary Grant).

But then, what is still the central tension? Is it this question who will Tracy marry? Or is it will Mike and Liz be found out as spies for Spy magazine? The latter gets dispelled rather quickly, so that’s not it. The former – well, that’s not really posed as a question until far later, when it’s clear that Tracy and Mike have some kind of a connection.

And the resolution – that her fiancé George (John Howard), unsure of Tracy’s moral rectitude, decides to leave her, Katharine returns to Dexter and gets “remarried” to him with the guests who should have been there when she first married him years ago.

Just writing all of that made my head spin. And so - is this why this is the quintessential screwball comedy?

One aspect of the film that people have rightly observed over the decades is class, and that came up in our discussion as well. A QFS member very astutely pointed out that this film is ultimately a very cynical take on class. George, the fiancé, has pulled himself up by his bootstraps from middle class (or poverty) into high society with Tracy and her family. But he is derided throughout the film from the start, with subtle jabs at his upbringing.

Take for example a simple scene early on, as pointed out by one of our members. George is at the stables with Tracy and the rest of her family. He is the only one who has trouble mounting a horse – presumably, he didn’t grow up with them on his estate – and everyone sort of laughs at him, even Uncle Willie (played with unnerving creepiness by Roland Young) rolls his eyes and says, “Hi ho, Silver” derisively.

Meanwhile, Dexter is still beloved by everyone except his ex-wife Tracy. Her sister, Dinah (Virginia Weidler) openly wishes he came to the wedding and when he does arrive at the house her mother (Mary Nash) can’t keep her hands off of him. This is a man, mind you, the very first scene of the movie we see of him shoving Tracy down physically with a palm to the face! But he’s forgiven by most and perhaps it’s because of a reason unsaid: he’s a member of the class and belongs with his kind.

Then comes Mike, played with Stewart’s uncanny everyman persona. He connects with Tracy and she finds depth in his writing and they are drunk and fall in lust or love or something. But even he – he of the working class – when it’s time at the end of the movie and he hastily proposes to Tracy, she rebuffs him.

The film seems to be saying – it’s all well and good to mingle between classes on some drunken weekend. But that’s all for fun because when it comes down to it you’ll get hitched to the one who is of your own kind.

This is a pretty stark take but it’s all there in the film. There seems no good reason to me, at least (and most of us) for Tracy to end up back with Dexter. Is it that Dexter has sobered up and has changed and she sees that? If that’s the case, it’s barely in the film’s narrative at all. Is it that Dexter now sees Tracy as not a goddess but as a human? That doesn’t come out either. If anything, Mike is closest to saying that Tracy has humanity and depth but even he treats her as if she’s this luminescent creature.

In the end, perhaps all of this ultimately doesn’t matter. Perhaps a loose plot is the maximum you need when you have legendary performers behaving badly. Jimmy Stewart is a downright fantastic alcoholic in this film, and Katharine Hepburn is no slouch either. You could do worse than watching ninety minutes straight of these two getting supremely sloshed and hamming it up on screen.

And perhaps, ultimately, that’s why this film has endured, what so many filmmakers today find this film unassailable as a romantic comedy. Maybe that’s all that matters in making a classic – a fun, slightly superficial, dastardly romp with the wealthy behaving in ways we imagine the wealthy to behave behind closed doors. Which is the exact assignment Mike and Liz were given in the first place. We, the audience, are the ones who actually get to see that story play out on screen in front of us.

Black Narcissus (1947)

QFS No. 131 - Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell are the powerhouse directing duo from England whose legendary work includes The Red Shoes (1948, QFS No. 52), The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), 49th Parallel (1941), The Tales of Hoffmann (1951), and of course this week’s selection The Black Narcissus. I’ve only scratched the surface myself with their career work but everything I’ve seen has been incredibly impressive.

QFS No. 131 - The invitation for December 13, 2023

Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell are the powerhouse directing duo from England whose legendary work includes The Red Shoes (1948, QFS No. 52), The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), 49th Parallel (1941) with Laurence Olivier, The Tales of Hoffmann (1951), and of course this week’s selection The Black Narcissus. I’ve only scratched the surface myself with their career work but everything I’ve seen has been incredibly impressive. It’s no wonder they are so influential to the following generation of filmmakers – Martin Scorsese and Spike Lee to name two – and I feel they need to be studied further by us and future filmmakers.

One of the hallmarks of Pressburger and Powell is their masterly grasp of film craft. The cinematography in their films is legendary and was duly awarded throughout their careers. Their art direction, costumes and set design are unforgettable. I point you to The Red Shoes for a textbook in the complementary usof all those elements as a case in point. Their numerous Oscar nominations for screenwriting and several for editing illustrate their excellence in storytelling for the visual medium.

Black Narcissus is one of those films I should have seen already. I know about its enduring cinematography and some of the story elements, but I’ve never seen it. It’s a big oversight in my viewing history that I’m happy to remedy now. I’m excited to finally see it and continue with my exploration of Pressburger and Powell.

Reactions and Analyses:

The wind. Besides the sweeping vistas, the first thing you really become aware of in Black Narcissus is the wind. Before we even physically arrive at the monastery, the characters make mention of how the wind is unavoidable up there, on the cliffside in the Himalayas above the village in the valley below.

And throughout the film, the wind is a nearly constant. It blows the fringes of the habits of the nuns, shakes the flowering tree branches and the tassels on the drapes. No matter what anyone does, the wind can never be dominated. There is an uncontrollable force that can never be mastered out there all around you and it’s folly for anyone who tries to master it. Worse – the attempt to control an unseen force like that can lead to suffering and madness.

To me, this is one of the overarching metaphors of the film. A group of white nuns come to a palace no longer used in order to turn it into a missionary, to bring their teachings, medicine and religion to a place and people who believe in other ways of being. The group is small and recent; the people already there are ancient and vast.

One way of looking at Black Narcissus is that it’s an interpretation of British colonialism, specifically in South Asia. A small group of people, atop a hill looking down on and away from the locals, are trying to remake a world they’re not normally part of. And they cannot. They can’t control the primal, human nature of the place. (The nuns, are temporary – the winds live forever. India achieves independence from England in 1947, which is the year Black Narcissus is released so this is a very plausible interpretation as it would’ve been on the mind of writer-director Brits Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger.)

The wind took up a good amount of our discussion about the film. To one QFSer, the wind felt as if it represented the spirit of one’s past, haunting you. Another said he felt the wind revealed yourself to yourself, like a mirror in which you are forced to look at your own image and reflect. It reveals yourself to you. Several of the nuns have joined the order because they have a past they were trying to leave, especially Sister Clodaugh (Deborah Kerr). The solitude of the place, the natural elements, the long vista horizon – Sister Phillipa (Flora Robson) mentions she’s staring to lose faith upon seeing the infinite up there – forces each to confront something about themselves.

For Sister Clodaugh, she hadn’t even thought about her old lover since joining the order – not until she was up on the mountain at the monastery. Then the place, the wind, brought those memories back to her. The primal forces bringing to life primal emotions and urges.

It’s impossible to watch this film and not be utterly swept away by the filmmaking craft. If ever there was a film in which you could feel the hand of a master filmmaker carrying you along, it’s this. (Or master filmmakers to be more accurate.) Everything is tightly constructed and deliberate. The camera pushes in slowly in mid-conversation, but only when needed. Sister Coldaugh puts out her hand to shake Mr. Dean (David Farrar)’s hand, but he instead grasps it gently and squeezes ever so slightly – an intimate moment played entirely in a medium 2-shot with a wide enough lens that the action in the background of the nuns leaving can still be seen. I couldn’t help but say that producers on shows I’ve directed would’ve been horrified if I didn’t shoot a close ups on each person and then an insert on the hand to really hammer it home. But here, the directors choose to play it in a medium 2-shot – so simple, so perfect, and conveys intimacy, sensuality and their connection.

Pressburger and Powell also use canted/Dutch angles selectively but that are so well composed that one QFSer mentioned that they convey motion and movement without actually moving the camera. The close ups fill the frame, with extreme close ups on the eyes or on lipstick being applied to the lips. Contrast that with the wide vistas throughout the picture. The control and firm tightness of the film definitely evoked their The Red Shoes (1948) that the duo makes the year after this movie.

Speaking of those vistas, those matte paintings – for me, this is one of the greatest films ever shot on stage that looks like it wasn’t shot on stage. (One in the group disagreed with me so there’s a difference of opinion on that.) Another QFSer brought up that by using the images of the Himalayas in that particular style (black-and-white photographs painted with chalk), the filmmakers set up the painterly aspect of the film from the start. It’s not “reality” but it’s a painted reality – something that’s heightened and even more beautiful than reality. This painterly set up allows you to accept those vistas and the disappear into the story.

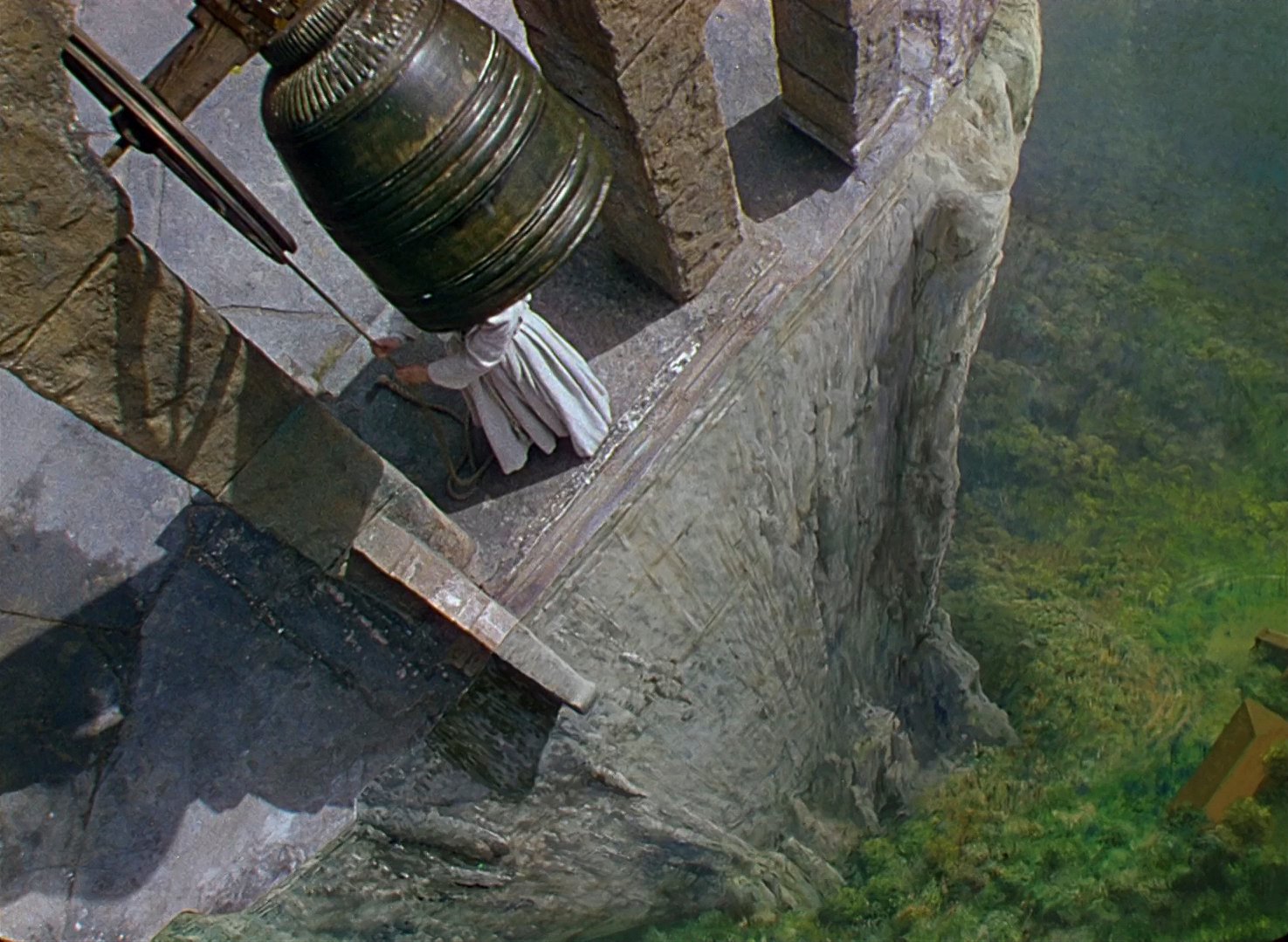

But it’s not just that they are beautiful, it’s what they represent. The vastness, the superiority of creation all around them, to me, makes the nuns not only smaller, but their mission almost meaningless and futile in the face of the abyss, the infinite around them. In particular, the part of the set with the huge church bell. The staging of this is astonishing. Not only is it on the edge and gives us a feeling that these nuns are all teetering on the precipice of stability, but the sheer (pun intended) technical feat of this – the directors had to have multiple matte painting backgrounds to simulate reality. There are the wide shots from behind the bell looking out towards the mountains. Then there are angles that show the bell, the nuns on the left of the frame, and the valley stretching out into the distance. And then, to top it off, there’s a high angle matte painting – a shot from above the bell looking down into the distant canyon floor below. All of these had to be conceived, planned out, then rendered in advance. The filmmakers couldn’t just walk on set and choose where to put the camera because they had to create that reality beforehand according to their vision in advance. It’s all so astonishing and inspiring.

It's been documented that Pressburger and Powell took inspiration from the Dutch painter Vermeer and his landscapes. A member of the group pointed out that it has a lot of single source lighting as well, evocative of the painting of Caravaggio. Which is no small feat for Technicolor stock that required far more light to properly expose than the human eye requires. Painterly is definitely an apt word for this film.

What genre is this movie? That is a question someone in the group asked. Of course, it’s drama – but could it also be a thriller, with a horror-like climactic resolution? There’s a warning early on by Mr. Dean that they won’t make it until the rains come. And, ultimately, that happens. But Black Narcissus in one way of looking at it is akin to a closed-room thriller where they all start to go crazy and then one attempts to kill one of them.

In an admittedly strange comparison, I brought up Danny Boyle’s overlooked Sunshine (2007) that features a mission to the sun to launch nuclear weapons into it in order to kickstart the failing sun’s heat. In Sunshine, everyone is on a mission, they start going crazy, and there’s somehow an entity on board who tries to kill them as the film goes on. It’s not a perfect parallel, but after seeing the slow burn of Black Narcissus there’s an argument to be made that this can be considered a thriller in many ways. (Another in the group brought up Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca, 1940, for its feel in the same filmmaking era.)

A QFSer brought up this exchange and its potential importance, which reflects the film’s title:

Young Prince: Do you like it, Sister Ruth? It's called Black Narcissus. Comes from the Army-Navy Stores in London.

Sister Ruth: Black Narcissus. I don't like scent at all.

Young Prince: Oh, Sister, don't you think it's rather common to smell of ourselves?

The group member’s assessment is that this is the thematic statement of the film. Here is something that’s being done to cover ourselves, to mask our natural scent. We humans all create a natural smell but we tend to hide it with something. For the nuns, it’s their faith masks their natural self (literally and figuratively), obscures their personal pasts. But you can only cover it – there’s the inner animalistic nature that we all have that either remains suppressed or emerges with time. And it can emerge in scary, deadly ways as it does with Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron).

In the scene where Sister Ruth puts on her make up – something that covers up something natural – Sister Clodaugh picks up the bible. Is this her cover? Is that what the directors are saying, that religion is a cover for the natural animal of ourselves? Perhaps, which sounds like a pretty subversive criticism of organized religion if that’s their intention.

There’s also something to the sadhu, the holy man who sits in reverent silence on the mountain top. Different religions orders come and go, but he remains there, unfazed. The image of an ascetic praying at the mountain, selfless, having achieved enlightenment and a oneness with everything around them is a common one in Hindu literary and religious traditions. Lord Shiva is often portrayed this way, long locks of matted hair, seated atop the Himalayas. This feels like the filmmakers are tying this into theme of colonialism trying to corral an ancient people and its faith, but it could also be an endorsement of a more mystical an ancient spirituality that worships out in the world and not confined within stone walls.

Left to right - Shiva statue atop Shiva Mandir in Bangalore (credit Darshan Karia), the holy man (uncredited or least I can’t find it) from Black Narcissus, Illustration of Shiva (artist credit unknown). Note Jean Simmons (Kanchi), the Indian bowing before him who is, notably, not actually Indian.

Which leads me to brown face. Do I Iike all the brown face, all the white actors playing South Asians in this film? I do not. I understand this is a “product of the time” and that argument is used as way to blow past criticism of using Jean Simmons (Kanchi), Esmond Knight (The Old General) and May Hallatt (Angu Ayah) as South Asians. But … come on. At the time they’re making Black Narcissus, India has a robust and growing film industry with many terrific actors who all are fluent in English. And though the film is being produced when the British are being finally kicked out of India, they are still intertwined in the Subcontinent. Pressburger and Powell could have easily gotten an Indian actor up to the standards of an international production and gotten them a ticket to London. I would almost buy the dearth-of-local-talent argument if Black Narcissus had been shot in 1946 Los Angeles where South Asians would’ve numbered at best in the dozens, as opposed to 1946 England where there are literally hundreds of South Asians at this time. As (soon-to-be-former) members of the British Empire who could study in London, just as Mohandas Gandhi and others had, there was a South Asian diaspora already living there. The production could easily have had a casting search for these actors but the fact is (and by that, I mean my educated guess) they simply didn’t want to because “at the time” people didn’t really care if they cast white Europeans and painted their face brown to make them ethnic. So it’s not lack of South Asian talent at fault here, but a lack of production effort. (Okay, end of rant. As a South Asian American, this rant has been my special privilege to contribute here.)

Aside from this (and from the utterly preposterous series of costume choices for Mr. Dean) Black Narcissus is an essential work. The conclusion is masterful. I was clutching my seat, not knowing who would die in the final scene. The deranged look of Sister Ruth – a look that one of our group pointed out must’ve influenced Stanley Kubrick a generation later – as she emerges, skeletal and red-eyed, as she emerges from the doorway is pure horror film perfection. And then that shot, looking up at Sister Clodaugh with the bell swinging behind her head as she gazes in horror down into the abyss has left an indelible imprint in my mind.

The final harrowing confrontation between Sister Ruth and Sister Clodaugh with its gripping imagery.

The rains eventually come and indeed, Mr. Dean is right – they made it until the rains but no more. You know it’s not a Hollywood film of the era. Here, someone at the beginning predicts the protagonists will fail and then they eventually do just that. There are scores of other films that would’ve seen these nuns triumph and overcome adversity. But the mission is doomed from the start. And in one of the final shots, the fog covers up the monastery high above as they are all leaving. This, like all of the shots in Pressburger and Powell’s masterpiece, is deliberate and not just a beautiful and poignant image. There are forces in the world that are too powerful for humans to control – from the external world to our inner nature – let alone comprehend, and an attempt to do so will certainly lead to doom.

How Green Was My Valley (1941)

We return to legendary John Ford, last seen in 2020 for QFS No. 26 with his Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), a film he made two years earlier than this week’s selection. The great American filmmaker turns his gaze outside the US in a film that won five Academy Awards including Best Picture. But to me it has always been known as “the film that beat out Citizen Kane.”

QFS No. 121 - The invitation for September 6, 2023

We return to legendary John Ford, last seen in 2020 for QFS No. 26 with his Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), a film he made two years earlier than this week’s selection. The great American filmmaker turns his gaze outside the US in a film that won five Academy Awards including Best Picture. But to me it has always been known as “the film that beat out Citizen Kane (1941).”

Perhaps that’s why it’s taken me so long to actually sit down and watch this movie. I’m sure I’ll be upset that How Green Was My Valley is inferior in its filmmaking to Orson Welles’ masterpiece, right? Citizen Kane has endured the test of time, gathering momentum over the 20th Century as arguably the greatest film ever made. Or at least one of them. Whereas How Green Was My Valley is probably most remembered for beating out Citizen Kane and The Maltese Falcon for Best Picture and for being one of John Ford’s 10 best films.

But Ford’s film batting average puts him in the directing hall of fame. He has a very very high percentage of excellence in his moviemaking, so I’m quite certain this will live up to expectations of a John Ford film. Also – and this is perhaps the best part of this week’s selection – the star of How Green Was My Valley is Walter Pidgeon, who was last seen in the 23rd Century as Dr. Morbius in Forbidden Planet (1956, QFS No. 119). So I’m going into this film considering it a Dr. Morbius origin story, before his brain capacity was expanded.

Join us in honoring the labor movement by seeing How Green Was My Valley over Labor Day weekend. See you then, comrade!

Reactions and Analyses:

How Green Was My Valley (1941) is the origin point of the immigrant journey. The village, provincial with generation after generation living in the same place, are dependent on a coal mine. The fate of that coal mine determines the fate of the people who live there. Eventually, men and women become faced with a choice - live as their ancestors have in a valley that’s steadily dying, or leave to greener pastures. (Note - “greener.”)

I was struck while I was watching How Green Was My Valley that this film could very easily have been adapted to India, from where my parents immigrated. I know others in the QFS group felt that it could’ve been from where their family original came from as well. There’s a universality to it that endures even now.

It’s a wonder how this film has been lost among John Ford’s others and has been overshadowed by Citizen Kane (1941). As mentioned above, I went into this film with the knowledge that it beat Orson Welles’ masterpiece for Best Picture at the Oscars. So comparing the two is inevitable so let’s take a moment to do so.

Why has Citizen Kane endured while How Green Was My Valley has less so? The group discussed this at length, but let me start with my takeaway between the two. How Green Was My Valley is beautiful, emotional and sentimental. It’s a story that feels specific to the characters but also universal in its emotional appeal, doing what cinema does best. Citizen Kane feels more intellectual, an exploration into the meaning of one specific life of fame, prestige and meaning. It’s perhaps deeper into its dive into the human condition in a way. It’s easy for me to see how Citizen Kane would influence the next generation of auteurs; Welles’ directing is the hand of an artist, using the cinematic tools to push the visual image and storytelling techniques to new places.

Ford’s hand in How Green Was My Valley is characteristically invisible - you don’t feel the overt hand of the director. It’s there, for sure - Ford is using all his skill to tell this story in the way he knows how. But his way is less overt, letting the characters, the story, and the more traditional cinematography doing the talking.

Other QFSers in the group felt like Citizen Kane is complicated and feels “important” in a way that you’re told something is important. Whereas How Green Was My Valley is just a good, solid story created in a way that you’re guided along the narrative and live with the people in this town as if you’re one of them. Citizen Kane - you’re kept at arm’s length. And this is, in part, Welles’ design - Charles Kane is an enigma that we’re unravelling in the film. Ford has us as a member of this village, rooted in Huw’s story (played by Roddy McDowell). We don’t even go up into the mine atop the hill until Huw does very late in the film.

How Green Was My Valley stands on its own as opposed to being the historic foil to Citizen Kane at the Oscars. In many ways, the bigger upset at those Oscars was that Gregg Toland’s astonishing and groundbreaking cinematography from Citizen Kane lost to Arthur C. Miller’s in this film.

In any event, How Green Was My Valley should instead be compared to Ford’s other films. There is no one like Ford in placing humans against vast landscapes. From the very opening, you see humans set against the large world around them, the hills rolling in the distance. Wide vistas with men in foregrounds and mid-grounds. The looming presence of the mill always hovering about the town, a clear symbol of dominance told visually.

Echoes of Ford’s word abound in How Green Was My Valley. Stagecoach (1939), Rio Grande (1950) and The Searchers (1956) come to mind seeing these Welsh landscapes. The Searchers in particular. Ford uses dark interiors with low ceilings that open up into the vastness of the exteriors - that’s done here throughout, but is of course legendary in the opening shot from The Searchers. Then for the story, you can see The Grapes of Wrath (1940) clearly in the pathos of the characters, their circumstances and being at the mercy of a faceless industry or corporation. Even Ma Joad (Jane Darwell) is analogous to Mrs. Morgan (Sara Allgood), long-suffering but spirited mothers trying to keep the family afloat. You can even find a man walking along the horizon in How Green Was My Valley in the way Ford shows Henry Fonda as Abraham Lincoln in Young Mr. Lincoln - where the preacher Mr. Gruffydd (Walter Pidgeon) has the nearly identical righteousness as Fonda’s Lincoln.

Similar use of horizon and vistas across John Ford’s films - left to right: Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), How Green Was My Valley (1941), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), Stagecoach (1939).

(Brief pause here to point out that Ford made from 1939-1941 - Young Mr. Lincoln, Stagecoach, The Grapes of Wrath, AND How Green Was My Valley?! That’s utterly incredible. I’ve left out Drums Along the Mohawk, 1939, The Long Voyage Home, 1940 and Tobacco Road, 1941 which are lesser films for Ford - all made before he left to serve and make films for the US Navy in World War II.)

A QFSer brought up that the film is a remembrance of the experience rather than the experience itself. The narration looks back at the events of the film with fondness but there’s tragedy and heartbreak in this old town. So the question is - why does Huw stay? He gets a scholarship to study in the city after doing well at school and even his father wants him to take that opportunity. After all, his brother died in the mine, people are dying all the time there. He likes school - but yet he decides to stay. We know he does because in the narration at the very opening he says he stayed in the valley for fifty years. Still, the allure of staying and working in a very dangerous industry is not clear to me other than he’s attracted to the widow Bronwyn - who is of course far older than him. I understand this is what his family has done for generations. But Huw has a ticket out. I guess that’s a sign of good filmmaking in that this decision frustrated me, which then led to the somewhat tragedy of his father dying in the coal mines.

We watched this film in the thick of the Writers’ Guild strike against the studios, right as Labor Day was approaching. The images in How Green Was My Valley of the strike stretching into the winter definitely hit close to home. Ford portrays the despair of this labor dispute with the coldness of the season and shows the desperation but determination of the workers. It’s easy to see the parallel between this and The Grapes of Wrath, how something wrought by a faceless entity, outside of one’s control - drought, bank failures, coal-mining greed - can decimate the working class and their families. It’s not exactly the same for us in the film industry, but I definitely feel some aspect of how Ford shows us this struggle.

How Green Was My Valley may not have endured the test of time in the minds of filmmakers or people who study cinema, but it’s not because of lack of merit. Perhaps just circumstance or timing or the fact that Ford’s work is so vast and so full of hits that this one just has fallen by the wayside. It’s no small feat to tell this tale - even though it has periodic narration from an older Huw, he’s not necessarily the main character. There is no one protagonist - it’s a story of a family and a village, featuring a truly excellent drunken party scene where people are literally drinking out of hats. To tell a sprawling tale like this is no small feat and can only be done if you care deeply about the characters, their story, and their struggle. It’s no secret that Ford is one of the all-time masters of this, and How Green Was My Valley is one of the many examples of why one must continue to study his filmmaking - even in some of his less remembered films.