Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964)

QFS No. 161 - Yes, Umbrellas of Cherbourg (`964) may not seem like a holiday classic. But it very well could be!

QFS No. 161 - The invitation for December 18, 2024

What kind of sicko would watch a French film from the 1960s during this time of the year when there is an entire subgenre of “Christmas movies” available at our fingertips?

You, is the answer. And me, more accurately.

Yes, Umbrellas of Cherbourg may not seem like a holiday classic. But it very well could be! It appears that way on at least one site I’ve consulted, and nevertheless I’ve had this movie on my radar for a long time. For starters, the visuals have inspired a legion of filmmakers, including most recently Greta Gerwig who cites it as one of her inspirations for the visual style and color palate of Barbie (2023). And it stars the great Catherine Deneuve in this unique musical from France.

Everything I’ve heard about the film is highly positive, including its inclusion on the BFI Greatest Films List where it’s 122nd Greatest Film of All Time, tied with There Will Be Blood (2007), The Matrix (1999), The Color of Pomegranates (1968, QFS No. 130), Johnny Guitar (1954) and Only Angels Have Wings (1939). Quite a logjam at 122nd! (Also, just after The Thing, 1982, QFS No. 115.

Look, I know – French film, and a musical no less! Have you gone mad? The answer is – have you seen 2024? It’s made us all a little mad. My dislike of musicals aside, I’ve heard great things about Umbrellas of Cherbourg and very much looking forward to seeing it on this, the 60th Anniversary of the film’s release!

So do join me in watching this, our final film of 2024 and discuss below!

Reactions and Analyses:

Early on in Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), one of Guy Foucher’s (Nino Castelnuovo) co-workers in the auto mechanic shop finds out that Guy is going to see the opera Carmen and can’t stay late at work or join them at the game. One of the co-workers says, “I don’t like operas. Movies are better.”

The great irony, of course, is that the co-worker is singing this line of dialogue, just as everyone is singing every line in this movie. Opera, being the other medium where singing from start to finish is what we expect. Here, of course, in Umbrellas of Cherbourg, everyone is also singing throughout – the throw-away line feels like director Jacques Demy’s fun inside joke to us, the audience, watching this film that’s more opera that movie.

The more traditional musicals, by and large, rely on a certain artifice of course and the musical numbers puncture the realism that movies attempt replicate on the screen. But with a musical, you know you’re watching something not-quite reality and any time a musical number begins it’s a necessary interruption from the narrative norm. Take an animated Disney film or a standard Hindi/Bollywood film – the narrative usually continues forward until the next musical number where you’re reminded you’re watching a musical.

In Umbrellas of Cherbourg, the music is constant and all the mundane aspects of life are sung. It was as if I was watching a movie in a foreign language (beyond just French) in which that’s just they speak in Cherbourg. I found myself giving in to the singing and in a way didn’t even realize I was watching a musical any longer. Once a film’s grammar or its style is established – could be fantastical or documentary style or neorealist – it’s easy to disappear into it. For me, I find myself as a viewer less able to disappear into a standard musical because of the puncturing of reality the musical numbers take.

But I didn’t experience that sensation in Umbrellas of Cherbourg – I was swept away into its world and could accept that even the mailman will sing his only line, saying he has a letter for Genevieve (Catherine Deneuve) or that the gas station attendant will sing when he asks whether she wants diesel or regular. The language was set and the grammar established and the rules were clear – everyone sings.

Our group also got to wondering: Is Umbrellas of Cherbourg the greatest wallpapered movie of all time? If not, what could be No. 1? The use of color in Umbrellas of Cherbourg, of course, have long been celebrated. But despite the vibrancy of the sets and costumes, the film is not candy and saccharine, which is what I had anticipated. The film contains teenage pregnancy out of wedlock, discussions about what to do about it, a depressed man visiting a brothel and hiring a prostitute, a dying aunt, going off to war, and a gas station of all places as a climactic romantic scene. Though it might look like it, this is not candy.

And the filmmaking isn’t candy either. There are no dance numbers, no nods to the audience except for that clever line about the opera at the beginning of the film. There’s nothing cutesy about the relationships - Genevieve’s mother (Anne Vernon) consistently berates her and is more concerned about what others will think about her pregnant teen instead of her actual well being. When Genevieve decides to marry Roland (Marc Michel) in order to avoid financial ruin, that montage is a prime example of how to advance time and story simultaneously. And in that advancing of time we get the hasty nature of the relationship - it’s full-steam ahead and Demy shows us how quickly events unfold from decision to marriage.

And this shot of Guy leaving for war and pulling away from Genevieve is utterly stunning and evocative - the music crescendos and Genevieve gets smaller and smaller in the distance and eventually out of Guy’s life altogether. It’s utterly perfect.

With the deft filmmaking and use of color throughout to enhance the storytelling, it's no wonder Umbrellas of Cherbourg have inspired contemporary filmmakers, most notably the costumes and set design utilized by Greta Gerwig for Barbie (2023) and much of the story, the color and the climactic sequences of Damien Chazelle’s La La Land (2016). But several of us in the group suspected that Spike Lee perhaps took some inspiration from Demy’s film as well. Guy has been drafted and about to leave for war in which he and Genevieve are in the alley in embrace. They’re moving but not walking, and the wall moves behind them as they sort of glide along – it’s one of the only non-realistic (other than the singing) moments in the film, so our attention is brought to it immediately.

Spike Lee uses this technique of putting the actor or actors and camera on a moving platform so often that it’s hard to list all the films he deploys this shot - most recently seen in BlacKkKlansman (2018, QFS No. 83). Demy is not the first to do this of course, but throw in the use of big bold colors on the set design and decoration along with the melodrama of the story, and it’s not too much of a stretch to believe that Umbrellas of Cherbourg had an impact on Do the Right Thing (1989) (especially given Lee’s admiration for great cinema that came before him).

The film has endured with filmmakers in many ways similar to the way Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet has endured over the years, I’d argue. Not on the historic magnitude as Shakespeare, of course, but Demy’s story about young impetuous love, missed opportunities, and bittersweet tragedy would be familiar to The Bard. Shakespearean melodrama elements all right there, tragic and beautiful at the same time. In the end, Guy and Genevieve never manage to build a life together and Guy is her daughter’s biological father – but they will never meet. And Roland has chosen to love Genevieve and marry her despite knowing she was pregnant at the time. We never see Roland again on screen but we see that Genevieve is now the wealthy wife and seemingly happy – though now, draped in brown fur as the wealthy do and not awash in the colors of her pre-motherhood youth.

And the final shot – perhaps arguably the most cinematic conclusion you can have at a gas station – suggests that although life didn’t work out as planned for either Guy or Genevieve, they have found a life that has made them happy, or at least content. It’s not the ending you expect of a standard musical, but if anything from the movie is clear, Umbrellas of Cherbourg is anything but standard.

Brazil (1985)

QFS No. 158 - Is now the right time to watch a film about trying to life under the gaze of a dystopic government with a crippling and heartless bureaucracy on the eve of what could be the downfall of representative democracy in this country?

QFS No. 158 - The invitation for November 27, 2024

Brazil is directed by Terry Gilliam, the mad-genius behind (and part of) Monty Python’s Flying Circus, the still-quotable Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), Time Bandits (1981), Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), The Fisher King (1991) in which Mercedes Ruehl* won an Oscar, the terrific 12 Monkeys (1995) and other films that are all a little ... askew. What a fascinating career Gilliam has had as a comedian, animator, actor and filmmaker. This is our first of his movies we’ve selected for Quarantine Film Society.

And this one is a favorite of mine – darkly funny, unpredictable and visually captivating, stunningly so at times. I first saw Brazil after someone recommended it to me while a student (…fellow…) at the American Film Institute and the movie stuck with me immediately. The story of how Brazil was made and released has become something of a dark tale itself. There are three versions of the movie that exist in the world – the original European release that’s 142-minutes long, the American version that’s 132-minutes long (probably the one you’ll find out there on streaming), and the so-called Sheinberg edit also known as the “Love Conquers All” version that’s only 90-minutes long. I’ve seen some aspects of each of these, and whatever you do, do not watch the Love Conquers All version because it’s an abomination.

Is now the right time to watch a film about trying to live under the gaze of a dystopic government with a crippling and heartless bureaucracy on the eve of what could be the downfall of representative democracy in this country? Sure why not. Good to know what’s in store for us! Eh.

Anyway, join watch and and discuss below!

*Not only was she later to be directed by yours truly in an episode of television, she also has the distinction of her first and last name sounding like a complete declarative sentence.

Reactions and Analyses:

There’s a sequence in Brazil (1985) that captures so much of what the film attempts to say about society, progress, perception versus reality and also captures director Terry Gilliam’s unique vision, all in one 20-second (or less) moment and series of shots.

Sam (Jonathan Pryce) is driving in his ludicrously tiny car, dwarfed by the wheels of a huge construction vehicle driving next to it. Then, the shot cuts from Sam’s face to what we presume is a POV shot of him driving through the city which we haven’t yet seen. This sort of cut is a conventional type of edit where we as the audience sees what he’s seeing.

It’s a driving point-of-view through a sleek, futuristic world with what appear to be cooling towers above uniform, efficient-looking buildings. But then, as the shot keeps moving (again, as though we are in the car looking out the domed windows as Sam is doing), suddenly a giant head of a disheveled-looking man holding a beer bottle appears above the buildings.

The moment is long enough to give us a sense of what is going on? Is this some sort of giant? But then it cuts to a wide shot of the actual city – this was just a model in a glass case of what the city was proposed to look like, with this drunken fellow now peering into it and Sam’s car driving past the model in the background through what the city actually turned out to be.

This sequence is illustrative of Gilliam’s work generally and themes of Brazil specifically in the following ways. First, it toys with filmic convention – we have an expectation of what we should be seeing (a POV) but the gag is a misdirect, played for laughs. But it’s also a commentary. People (government or businesses) promising one thing but the reality ends up being something totally different – both the shot and the subject in the shot (the cityscape). The wide shot shows the same towers as the model, but run down, graffiti covered. It’s no mistake that these buildings are named “Shangri-La Towers,” an elevated name for a dilapidated place.

Hidden in this is a third aspect: who is to blame for these promises not being kept? And are we simply powerless to hold anyone accountable?

We are victims of indifference to our circumstances in an uncaring world, Brazil tells us. Bureaucracy (paperwork!) is dehumanizing – no one takes responsibility because in a world where authority is both decentralized and opaque, there’s no one person to blame. Everyone is at fault therefore no one is. As perfectly described in this exchange:

Sam Lowry: I only know you got the wrong man.

Jack Lint: Information Transit got the wrong man. I got the right man. The wrong one was delivered to me as the right man, I accepted him on good faith as the right man. Was I wrong?

That wrong man was poor Archibald Buttle (Brian Miller) who later died after being taken away in a case of mistaken identity – in that, they have the wrong name entirely and are looking for Archibald “Harry” Tuttle (Robert DeNiro). Jill Leighton (Kim Greist) attempts to find out what happened to her neighbor Mr. Buttle but since he’s considered a criminal, she’s only met with institutional indifference, given the ol’ run-around.

Sam, however, is in the system. So surely he can fight it – that’s where we think the film is going. Someone who is of the system but doesn’t really care for it will use his knowledge of the system against it to take it down and make the world a better place.

Gilliam, however, isn’t one for the Hollywood convention of a happy ending (as is thoroughly documented in his fight with Universal Studios and Sid Sheinberg to get Brazil released back in 1985). Instead, Sam, who has apparent privilege as a worker drone in the Ministry of Information and as the son of a prominent member of the government, in the end can’t defeat the system nor can he prevent himself from being a victim of it either.

One of our QFS group members brought up this phrase that I’ll try to remember when talking about Brazil in the future – it’s Kafka meets Capra. Comparisons to George Orwell and his 1984 are of course impossible to miss, but it’s not entirely accurate. The seminal book paints a bleak and ultimately joyless world living under a totalitarian state. Brazil’s world isn’t quite as bleak – in fact, the rich among them are very happy. They can endure routine terrorist attacks as “poor sportsmanship” and can continue to eat brunch so long as a barrier blocks them off from the horrors unfolding behind them. Or they can completely change their appearance with the right cosmetic surgeon. And Sam’s inner mind is full of fantasy and light - he’s actually fighting the system in his dreams, as opposed to being swallowed by it in reality.

Although the less wealthy and poor are victims of an uncaring world – the Buttles, for instance – Gilliam plays all of this for absurdist laughs as opposed to bleak sadness. The film is satire, not a post-apocalyptic look back at a world lost as we inhabit a brave new world. Gilliam has said that Brazil does not take place in the future and even the title card says “somewhere in the 20th Century” (which now of course puts this film firmly in the past). So it’s about our present day where consumerism is most important, a world where a child asks Santa for a credit card, a procession marches by with people holding up “Consumers for Christ” banners, and the guard implores Sam to confess quickly otherwise his credit score will suffer. Twentieth century “satire” here comes dangerously close to full on 21st Century reality.

And, I dare say, the film does find a way to have something resembling hope. Well maybe not as far as hope, but one can interpret that, in the end, Sam has found a place unreachable by the overbearing State – his innermost mind. The ending – the very ending, not what appears to be ending with Sam being rescued by the very terrorists he’s accused of being a part of – but the final moment of Sam in the chair humming the tune that’s the film’s namesake. He has gone off into the sunset with a woman he loves, free from paperwork and the dirty city.

Or, maybe they’ve already performed the lobotomy and it’s as bleak as saying – whatever you do, the State wins in the end (as does Big Brother in Orwell’s work). It’s unclear here in Brazil, but what’s clear is that the filmmaker shows a man in a chair surrounded by darkness, only to have that darkness dissolve into clouds and the world of his dreams. To me and to several of us in the discussion group, that is a glimmer of something brighter from the outside world.

Much has been written about the groundbreaking production design and imagery in the film and what’s striking about seeing it now, in the 21st Century, is that this film was made at all. In our current movie landscape, only a two or maybe three directors are able to create an entire world something as big, bold and maniacal as this – perhaps only Christopher Nolan, Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese and maybe Denis Villeneuve – without relying upon pre-existing source material. “I.P.” to use the language or our times. And Brazil is a lot for a first-time viewer, we discovered – it’s full of visual gags and stimulation, extraordinary camera work, clever dialogue with that Monty Python-esque British humor inflected throughout. You could watch the film all the way through just for the propaganda signs throughout (“Suspicion breeds confidence.”) And it’s just a utter stroke of genius that this whole thing is set off by a bug falling into the printing machine. A system so confident in its infallibility but yet the tiniest of creatures can cause it to fail.

Brazil is full of big ideas packed into a madhouse of a film. If there’s one thing we’re missing, one sadness at revisiting a work as innovative and inventive as Brazil, is that there are so few of its kind since then. So few original films on that scale that are about ideas. Perhaps Nolan is the only one making inventive big world creation films about ideas. There’s a bleak homogenization in our movies, one big action or comic-book based film looking almost exactly like the next. It’s our version of being surrounded by gray walls.

Are we living in Gilliam’s Brazil or some version of that now? I don’t think it’s as bleak as all that. After all, we’ve all but gotten rid of paperwork.

Princess Mononoke (1997)

QFS No. 157 - We are all long overdue to be taken away to a different land. At least for a couple of hours. And there’s perhaps no one better suited to take us elsewhere than the Japanese master of animation, Hayao Miyazaki.

QFS No. 157 - The invitation for November 20, 2024

We are all long overdue to be taken away to a different land. At least for a couple of hours.* And there’s perhaps no one better suited to take us elsewhere than the Japanese master of animation, Hayao Miyazaki. We have technically never selected a Miyazaki directed film, but his Studio Ghibli produced Grave of the Fireflies (1988, QFS No. 23), which was the first animated film we selected to watch for Quarantine Film Society.** Studio Ghibli films’ streaming distribution opened up more widely recently, which is an exciting development and will make it easier to see all of these great Miyazaki masterpieces.

Princess Mononoke is high on that list. In 1997, there was not yet an Academy Award for animated feature. Had there been, Princess Mononoke would’ve been the odds-on favorite to win that year. Disney, who dominates the category, had the above average Hercules (1997) and Anastasia (1997) – not classics, which is how Princess Mononoke is often described.

Fast forward a few years when the Oscar category was created, and Miyazaki takes home the statuette for Spirited Away (2001), a truly magnificent film that I’d rank among the greatest animated movies of all time. And just last year, at 80-years old, Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron (2023) won the top animated prize again. My Neighbor Totoro (1988) remains a favorite around the world. Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (1984) are among the titles that are celebrated by anime fans and others alike – and there are dozens more.

Miyazaki’s storytelling contains magic on par with Disney’s, but I’d argue even more so with stories that are layered and contain even deeper explorations of character and the soul. His stories take on complex emotions and never pander to the audience – which we definitely saw in the post-war tale of Grave of the Fireflies. Though animation as a medium is often aimed at children, his stories cater to adults as well, often with haunting imagery and disturbing sequences. Miyazaki has elevated the medium and the genre and has made an indelible mark on the film industry as a whole.

I’m very much looking forward to finally seeing Princess Mononoke. Disappear into Miyazaki’s world for a couple hours and join us to discuss here!

*Ideally, longer.

**Flee (2021, QFS No. 69) is the only other animated film we’ve selected due to a long-standing bias among some members of our QFS Council of Excellence (QFSCOE).

Reactions and Analyses:

At the end of Princess Mononoke, the victor is nature. The enraged, decapitated Forest Spirit has just decimated Iron Town, the human-made walled outpost that’s been mining ore and decimating the forest in its path. Iron Town’s ruler Lady Eboshi (voiced by Minnie Driver in the English dubbed version) has had her arm bitten off by the wolf goddess Moro (Gillian Anderson).

But San (the titular Princess Mononoke, voiced by Claire Danes) and the story’s main protagonist Ashitaka (Billy Crudup) have retrieved the head and returned it to the Forest Spirit, healing it and the cataclysm has ended. In the spirit’s wake, the Iron Town is destroyed - but it’s not the end of the story. Instead, over all the destruction, sprouts being to spring and grass grows and nature reclaims the land. In the end, nature is victorious.

If there’s a central idea of Princess Mononoke - and there are several, some that were a little harder to discern for us in the QFS discussion group - it is this: nature will endure and prevail, if we help it. If we, as humans, can live in harmony with it, symbiotically.

It’s no surprise that several movies including Avatar (2009) are influenced by Hayao Miyazaki’s epic story in Princess Mononoke - from both a story perspective and also visually. But what sets Princess Mononoke apart from Western fare including Avatar is that neither humans nor nature are all entirely good or entirely bad.

Take Iron Town. The town is clearly destroying the land and exploiting its resources. Lady Eboshi is an unrepentant capitalist hell bent on ruling the world. (In fact, she holds up a newly created rifle saying that it’s a weapon that you can rule the world with.) But even she has more layers than that - she is not the villain of the film, to the extent that there is a villain of the film.

In fact, it’s quite the opposite - she is extremely benevolent. We learn she took women out from working in brothels and gave them dignity and power - but also putting them to work in the bellows of the iron works. She’s taken in lepers who were cast out from society - but also has given the task of making weapons for Lady Eboshi’s growing empire.

In this way, Miyazaki is pointing out something that we see every day in real life. Large corporations whose business is tearing up the Earth for resources to fuel modern economy and industry, claim that they are benevolent. Sure we’re extracting fossil fuels and poisoning the atmosphere, but we’re also providing jobs, education, and look how many renewable energy projects we’re funding!

All of the characters are complex in this way. Even nature isn’t all good either. The wolves are particularly nasty, threating to bite off Ashitaka’s head at any given moment. The boars in particular are brutish, headstrong and unwilling to compromise. It’s their inability to let go of hatred that brings on the demon - or something like that.

Which is one aspect of the film we all found confusing - the rules and the mythology. Narratively speaking, the first half of the film or so is breathtaking in its scope and clear in its vision of a journey for Ashitaka to find a cure for his arm and “to see with eyes unclouded by hate.” But in the second half, Ashitaka encounters humans at war - samurai versus Iron Town, messy allegiances, even in the forest with the animals including the apes. And in the end, after all is said and done, Lady Eboshi and the conniving Jigo (with strangely aloof voicing by Billy Bob Thornton) receive no comeuppance. Eboshi does have an arm cut off, but even when nature is restored there is nothing to suggest, necessarily, that she’s going to change her tune and live in more harmony with nature. And Jigo - whose mission was to decapitate the Forest Spirit at the Emperor’s behest - survives and shrugs it all off.

Perhaps this, too, is Miyazaki’s point several in our group contended - that these people continue to live among us. People who would live in discord with nature, with ill intentions who are only looking out for themselves. So this balance between nature and life will continue. And it’s also true that we, as American filmmakers and viewers, expect a narrative arc or change in a character. But in the East, perhaps that’s less necessary or expected - even in an animated film. After all, Ashitaka doesn’t really change at all, if you consider him the protagonist - he begins righteous and stays righteous. If anything, he’s trying to have everyone fight against resorting to anger and destruction and he loves the people of Iron Town but also Princess Mononoke and the denizens of the forest. San (Princess Mononoke) in fact still distrusts humans and her human self and doesn’t actually end up with Ashitaka.

Despite this lack of a narrative arc we’re hoping for as Western audience members, Miyazaki is painting a picture of there is no good and no evil. Nature itself destroys and brings to life. The Forest Spirit saves Ashitaka but also kills plants and destroys the countryside, just as life springs forth beneath its feet.

Miyazaki has mastered the animated film. But what he’s done to elevate it is that he manages to make the fantastical feel realistic. He manages to make the world three-dimensional, as if it’s there’s a camera on that hillside filming the wolves as they carry the masked San/Princess Mononoke, dodging real rifle shots. It’s a truly remarkable experience to disappear into a Miyazaki world.

But the world he’s creating, especially here in Princess Mononoke is a mirror to our world - a plea for what he hopes is ultimately balance in a world living in the absence of that balance, teetering on mutual destruction.

Near the end of the film, Princess Mononoke/San says, “Even if all the trees grow back, it won't be his forest anymore. The Forest Spirit is dead.”

Ashitaka replies, “Never. He is life itself. He isn't dead, San. He is here with us now, telling us, it's time for both of us to live.”

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974)

QFS No. 154 - Rainer Werner Fassbinder is one of those filmmakers whose work I, as film snob and student of film, should have seen. But instead, I pretend I know about Fassbinder – of course I do. I went to film school, you see.

QFS No. 154 - The invitation for October 9, 2024

Not to be mistaken with Ali (2001), the Michael Mann biopic about Muhammad Ali. Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, as far as I know, has very little boxing and probably even less Muhammad Ali in it. But who knows!

Rainer Werner Fassbinder is one of those filmmakers whose work I, as film snob and student of film, should have seen. But instead, I pretend I know about Fassbinder – of course I do. I went to film school, you see.

Consequently, I know very little about Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, but more than one person has recommended it to me in recent years. One institution gives this film high marks as well – specifically the British Film Institute, where it came in at No. 52 on the Greatest Films of All Time List. You’re familiar, of course, with the oft-cited/derided BFI/Sight & Sound list that comes out every decade. Well, Ali: Fear Eats the Soul is tied in 52nd I’ll have you know. Tied with (checks notes) News From Home (1976) directed by Chantal Akerman – you all know her as the director of the No. 1 Greatest Film of All Time, Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975, QFS No. 98).

Anyway, I’m looking forward to seeing my first Fassbinder film, which will be our third German film after Aguirre: The Wrath of God (1972, QFS No. 40) and Downfall (2004, QFS No. 28) – so it’s been about 112 films since our last time with the Germans. See Ali: Fear Eats the Soul and add Fassbinder to your snobby film cred as well!

Reactions and Analyses:

There’s a scene more than halfway through Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974) that feels like a fulcrum of film. Moroccan-born Ali (El Hedi ben Salem) and the older German widow Emmi (Brigitte Mira) have fallen in love, but their uncommon pairing has drawn the ire of nearly everyone they encounter. Emmi is shunned by neighbors and co-workers. Her grown children stormed out in anger, with one son Bruno (Peter Gauhe) even kicking in the screen of her TV set.

All of this Emmi accepts with grace, and feels that people, though surprised at their relationship, are eventually going to come around. She knows she’s old and people are prejudiced against people from the Arab world. But in this scene, her fortitude has run out. They’re in an outdoor café, in a plaza, surrounded by yellow chairs. Not one sits next to them, they’re in the center of their own world. All the café staff stand back and away from them, simply staring.

Emmi and Ali hold hands across the table and Emmi breaks down. She lashes out at them, at the world, for treating them this way when all they want is love. Ali tenderly strokes her hair to console her. The scene feels like a tipping point, the moment in which Emmi’s underlying belief in the ultimate goodness in people has cracked.

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul feels as if it could’ve taken place today, that it could be a contemporary story. It is a contemporary story – you can imagine these characters swapped with someone who is African American or Latinx or, well, Arab. Prejudice and racial discrimination is not unique to any one country.

What makes this film so unique, however, is that this is Germany not quite 30 years after the end of the Second World War. The references to Hitler are surprisingly casual and off-handed and suggests to me that director Rainer Werner Fassbinder is making a comment about his own country’s lingering difficulty with race and prejudice. Instead of blaming Jewish people for their ills, characters throughout blame the immigrants from Arab-speaking countries.

Emmi’s son-in-law Eugen (played by Fassbinder himself), a vile misogynist, bristles at the notion that his superior at work is Turkish. He sulks at home “sick” but clearly just lazy and drunk, demanding beers from his wife Krista (Irm Hermann), The two couple are miserable with each other, constantly insulting and clearly hate each other. Fassbinder seems to be deliberate about the juxtaposition of this scene with the previous one, which is after Ali has left Emmi’s place and the two have made love in the night. People may look down on Arabs for being “swine” and lazy, cramming in homes instead of buying their own place (according to the ladies Emmi works with), but Fassbinder forces us to see that this is untrue – just look at how miserable Eugen is and his home life with Krista. If anything, native-born Germans are the ones who are taking their good fortunate and privilege for granted.

But everything is deliberate with Fassbinder, we found. The compositions are steady still, often using doorways or the staircase to provide a frame within a frame or obstacles to our viewing. He moves the camera only when needed and with great effect to bring our attention to something in particular.

Take the opening scene. There’s beautiful, hypnotic Arabic music playing and a woman steps in from the rain into a place, drawn by the music. She’s a stranger here – the frame is still. The reverse angle, her perspective, we see everyone straight upright staring back at her. Their posture speaks volumes, as if to say something’s not right here. Then the bartender Barbara (Barbara Valentin), comes around the bar and the camera pushes in, she passes buy which creates extra dynamism in the camera move and it pushes closer to Ali, who we are introduced to here, in a way.

There are numerous instances when the camera’s movement is precise, purposeful, and helps tell the story in this way. Or lack of movement. Emmi and Ali go into an Italian restaurant (“Hitler used to go here!” is an unsettling plug for this place) after they’ve been married in court, and Fassbinder keeps his distance, playing much of the scene from another room through a doorway. It’s cold, like the reception they’re getting from the waiter as strangers in this place.

Although it had been well documented, I was previously unaware of Fassbinder’s connection with Douglas Sirk and about how he was inspired by the German ex-pat’s work in the American film industry. Sirk, who we just recently selected two films ago (Imitation of Life, 1959, QFS No. 152) mastered melodrama, but also mastered the ability to take on socially provocative subject matter. In Imitation of Life, it’s race, just as it is in Ali: Fear East the Soul. Several people over the years have pointed out that All that Heaven Allows (1955) is a direct parallel to Ali: Fear Eats the Soul – an older woman and a younger man fall in love – but Fassbinder supercharges it with race. But he does it in a way that’s even more evolved than Sirk, in my opinion.

Where Sirk does an admirable job tackling social touchpoints, specifically race in Imitation of Life in during a time where racial discrimination was high in America – Jim Crow laws still very much in effect throughout the South – Fassbinder inflects his story with another angle. Both characters are lonely. We can see the stress it inflicts on Ali as an Arab in that it actually starts to kill him. But he strives for any sort of comfort from home – couscous, for example. (Which led to this trenchant over-simplification by one in our group: “Can you make me couscous? No? I’m leaving.”)

It’s this loneliness that bring these two together. Is that enough to sustain a relationship? No, and it frays. But they come back together and there’s a sense that they truly do love each other, even though Ali is stoic and speaks in broken sentences.

If there’s a shortcoming of the film, is that Ali at times is objectified. This is possibly a comment as well by Fassbinder – he’s seen as one-dimensional if it fits someone’s needs. The woman feel his muscles, ask him for help, admire how young he is once people start to suddenly accept their relationship. Even the son comes and apologizes for breaking the television and sending a check. But even he is angling for something – he needs childcare from his mother to look after her grandkids when they need it.

So we don’t see Ali’s perspective enough, in my opinion. Had we been given a chance to see Ali speak in Arabic, for example, we wouldn’t see him as a brute as much, would see that he’s intelligent and thoughtful, perhaps, in ways that don’t come out as much when he’s struggling to speak in German. And see him comfortable in the other half of his dual identity as an Arab German.

One member in our QFS discussion group pointed out that we only see the racism and how people treat them after their married, and no other sense of their homelife. It becomes a bit too much, overly taxing, and gives us the feeling that the only thing they experience is racism. True, that’s the feeling conveyed, but if they love each other we could do with at least one or two scenes of domestic bliss. After all, we’re led to believe that they truly love each other and not that Ali is in this for some other gain or that she’s using him to stave off loneliness.

All this aside, Fassbinder’s stripped down film is somehow captivating. It’s this bare-bones feeling, this lack of cinematic tropes – which is far different than Sirk, by the way – that gives the impression of realism. Not Realism in formal sense, but a feeling that this is a very believable, realistic story that’s happening right now as we watch it unfold. And probably that’s because it is a story happening right now, every day, in many places around the world.

Sicario (2015)

QFS No. 153 - I’m sure many of you saw Sicario (2015) when it came out or in the ensuing nine years afterwards. I, however, am not one of them, hence this pick. It’s been on my list for a while, especially because of the filmmaker at the helm.

QFS No. 153 - The invitation for October 2, 2024

I’m sure many of you saw Sicario (2015) when it came out or in the ensuing nine years afterwards. I, however, am not one of them, hence this pick. It’s been on my list for a while, especially because of the filmmaker at the helm.

Denis Villeneuve is one of my favorite directors working right now. Arrival (2016) is a modern classic that got short shrift at the Academy Awards that year but I know will endure the test of time (really solid movie year with Inside Out, Mad Max: Fury Road, The Revenant, Ex Machina, Creed, The Martian, Spotlight, Brooklyn, The Big Short and the new Star Wars trilogy launched). For Villeneuve, I’ll go so far as to say his Blade Runner 2049 (2017) rivals or perhaps surpasses its legendary predecessor (come at me!). Dune (2021) is arguably his “worst” of those three it’s still a monumental and fantastic (half) a movie.*

All of these films above are likely vastly different than Sicario, which is what I’m most interested in seeing. He’s mastered atmospheric other worldly stories and landscapes, I’m very curious what he does with the Mexico-US border.

If you haven’t seen it or even if you have, please watch or rewatch join the Sicario discussion!

*I somehow haven’t seen Dune: Part Two (2024) yet which is why it’s left off this list but I’ve heard good things which is just as good as seeing it right?

Reactions and Analyses:

Moments before the climactic sequence of Sicario (2015), there’s a shot in the film that evokes a specific genre of movie. It’s low light, the sun has set but there is striking reds and oranges and light in the distant horizon. The figures move in silhouette, in unison as the camera moves parallel to them, wide. The figures – some close in foreground and others in the back all wear military helmets and hold military weapons.

When I saw this shot, everything in the movie clicked for me – this is a war film. The shot is appropriately similar to imagery in Jarhead (2005), a film about the futility and Sisyphian nature of war – also photographed by the legendary Roger Deakins who is the cinematographer in Sicario as well. It’s a classic shot you’d see in a film about the conflict in Vietnam or in Middle East or Afghanistan. But here, in Sicario, the battleground is the US-Mexico border, not some far off world.

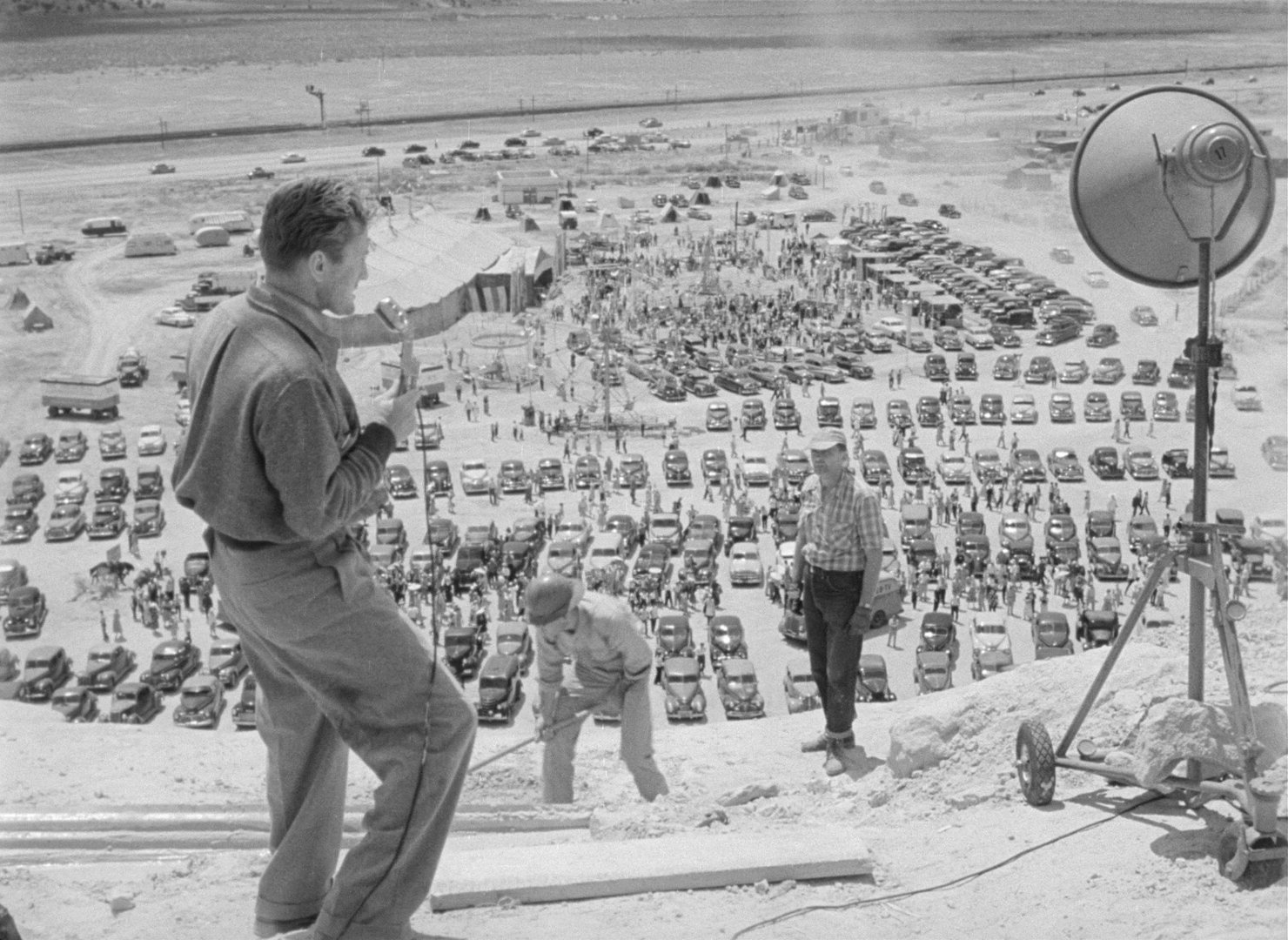

Not a shot from Sicario but from another Roger Deakins shot film, Jarhead (2005) - another film about war.

The composition here – as well as the narrative and themes that precede it – is no accident. The screenwriter Taylor Sheridan and director Denis Villeneuve have a thesis, and that thesis is that this conflict, this so-called “drug war” is indeed war. Full-blown war. Not a criminal enterprise of cartels and traffickers and something to be dealt with by the justice system. It is war. And thus, quaint rules of due process, legal procedure and the rule of law don’t apply. Because this is war, and your attempts to treat it differently are at best naïve and at worse a danger to the people of America. After all – look how brutal the faceless cartel is – they’re beheading people and hanging their bodies in major cities.

And in war, you must do what is necessary to defeat the enemy. To destroy these monsters, we need to become and embrace monsters.

This thesis, if accurate, explains so much of the behavior of the characters in the film. Kate Mercer (Emily Blunt) is a proxy for the American people. An FBI agent, but she’s in the dark just as we are for most of the film, only given a little bit to know when it’s right. But the men around her – they know what’s best. Rest your pretty head, you don’t know what it really takes to get the job done, or so the message comes across in Sicario. It takes men willing to do ruthless things, bend the rules, break laws. That’s what it takes.

Perhaps this is the cynical way to look at the film, but it feels very much in line with what Villeneuve and Sheridan are trying to say. In this way, it also feels deliberate that the character cast is a woman, unable to be taken seriously in a world where the only solution to our problems lies in bravado machismo and brazen law breaking in the service of “national security.” I hesitate to bring this up, but the only Black man in the film Reggie Wayne (Daniel Kaluuya) and the only woman are the only two who are portrayed as naïve wimps following “rules” like wimps do. Another way of looking at it (that one of our QFS discussion group members brought) up is that they are the only two following a moral compass. That is giving the filmmakers more credit than I’m willing to give them, but it’s valid. The other way to look at it, however, is that this Black man and White woman are diversity hires who don’t have the stomach to do what needs to be done to keep us safe. Yes, this is very much a cynical take but the evidence in the film itself suggests this interpretation.

Sicario feels very much like a post 9/11 film. People entrusted with keeping America safe explicitly violated American moral values in order to do so. The film very much has that tone and I, for one, don’t love this aspect of the film. (I can disagree, of course, with what a film espouses while still thoroughly enjoying it – as I did with Sicario.) Matt Graver (Josh Brolin), after all, specifically does not want to select someone who went to law school, as Reggie has, because they know their at best skirting the law and at worst overtly breaking it.

And throughout, the team condescends to Kate, keeping her in the dark and in the end it’s even clearer – they’re using her, including her loneliness as bait to lure in a corrupt cop (Jon Bernthal). Specifically, they’re using her status as an FBI agent to justify the CIA operating on American soil, which is otherwise against the law. But law doesn’t matter when you’re at war, as the filmmaker appear to contend.

Some in the group believed the filmmakers are just presenting the world as it is, showing what it’s really like. And here’s where I disagreed with them. It’s not just a simple expose, if you will; the filmmakers are expressing an opinion. For example, at the end Alejandro (Benecio del Toro), the shadowy international double agent of some type, has broken into Kate’s apartment to put a gun to her head and force her to sign a document saying that everything they did followed the law. But now, after Kate has seen Alejandro kidnap and kill in Mexico with impunity – in fact, he shoots her to disable her when she tries to stop him. Now in her apartment, she reluctantly signs the document, knowing that Alejandro will go through with it.

As he leaves, he says: “You should move to a small town where the rule of law still exists. You will not survive here. You are not a wolf. And this is the land of wolves now.”

If this is not a thesis statement, I don’t know what is. As well, the opening title card says The word Sicario comes from the zealots of Jerusalem, killers who hunted the Romans who invaded their homeland. In Mexico, Sicario means hitman.

“Invaded” and “homeland” here are deliberate, as is the framing. The Roman Empire was the ruling governmental authority, so if you swap America for Rome and the “zealots of Jerusalem” as Mexican drug dealers and drug lords – well, that’s a pretty stark interpretation. I’m not saying it’s completely inaccurate, but when you’re using those terms it definitely justifies violence for some folks out there.

Filmmakers should have an opinion, a thesis, An opinion makes a film better, gives it direction and that driving force is felt throughout the incredible craft of the film. Villeneuve is a master of showcasing scope, perhaps one of the best filmmakers using aerial photography working today. The sequence of black SUVs crossing the border from the US at Nogales into Mexico is hypnotic, ominous and incredibly effective at building tension. Similar work can be seen throughout Villeneuve’s recent work – Dune (2021), Blade Runner 2049 (2017), and Arrival (2016) are masterclasses in portraying scale and scope.

But Sicario, with all the stunning craft work helmed by Deakins and Villeneuve, it still comes down to something personal. Alejandro breaks into Kate’s home and forces her to sign the document, he leaves her apartment. She gathers herself, grabs her service weapon, and rushes out to the balcony in the cobalt dusk.

She points it at him in the near distance and he turns to her, opening himself up to be shot. Kate, shaking with a bloody eye from the firefight in the tunnel earlier, is unsure what to do. Alejandro opens himself up to her, giving her a clear shot. This moment is one of the most powerful in the film. It’s where performance, cinematography, directing, story, and theme all intersect. What will she do? Will she act as they would, act outside the judicial system and be judge, jury and executioner? In the battle’s aftermath, she told Matt she’s going to report all of it to the higher ups – but will she? Is this better?

She relents. She can’t go through with it, and he walks away. It’s a fascinating scene and we all had varying interpretations of it. Some felt that Kate realizes that Alejandro is right, that this is the way it works. She may not like it, but his way is the right way. Others felt that perhaps she knows killing Alejandro will not end anything and she, herself, will become like him – a fate she does not prefer.

I took it to mean – Kate is bound by law, by the moral code of America. If you believe she’s a stand in for us, the general public, she has an obligation to follow that code. After all, she tells Matt this after the raid and battle in the tunnel. And Alejandro knows that. He knows she’s powerless in this world. She’s not a wolf.

And in the end, is Alejandro right? Are the filmmakers right, is the drug war only winnable if we commit to it as if it is a war? One member of our QFS group is a political scientist shared that he has a mentor from Mexico that works on issues of jurisprudence in that country. To paraphrase, though she is committed to the rule of law and governance in Mexico, she entertained the idea that perhaps maybe in this circumstance – you indeed need wolves.

Perhaps. But isn’t it true that wolves beget more wolves? In a land of wolves, what happens to the sheep? Are they all eliminated? The filmmakers pay some service to the sheep, with the somewhat innocent Mexican police officer (Maximiliano Hernandez as Silvio) who transports smuggled drugs in his police car. We see his son, his very modest homelife, and you get the sense that he’s not a violent criminal but just someone who is getting by, bending the law to survive. Until he’s callously killed by Alejandro and left to die on a dark highway. In the film’s coda, the officer’s son plays soccer near the border when gunshots are heard in the distance and everyone stops and turns towards it, before resuming play.

This is the only nod, really, the filmmakers pay to what is happening to the sheep in the land of wolves. It feels tacked on, an afterthought and thin compared to the complexity of the other characters and their storylines in Sicario. This has all the hallmarks of American arrogance – the story focuses on the American side of it, told through the American’s point of view. Matt, after all, accuses American drug users of being the ones who are causing all the harm. The true victims are the people of Mexico, however, where the sheep are being slaughtered by wolves. Perhaps the last thing they need are even more wolves.

Imitation of Life (1959)

QFS No. 152 - Director Douglas Sirk’s name is synonymous with melodrama. As someone who studies film and works in entertainment, this is one of those givens you know about even if you don’t know his movies.

QFS No. 152 - The invitation for September 25, 2024

Director Douglas Sirk’s name is synonymous with melodrama. As someone who studies film and works in entertainment, this is one of those givens you know about even if you don’t know his movies. I first learned about Sirk when Todd Haynes’ Far From Heaven (2002) hit the theaters. When it came out, Haynes made it clear it was an homage to Douglas Sirk films, in the story, the time period, and the style of the filmmaking.

Sirk, a Danish-German filmmaker was one of the many artists forced to flee persecution from the Nazis in the 1930s, just as Fritz Lang and Billy Wilder had to in the same era. Sirk made several German films before leaving the country and even directed short films into the late 1970s long after retiring from Hollywood filmmaking. I’ve been eager to see one of the classic Sirk melodramas – All that Heaven Allows (1955), Written on the Wind (1956), and this week’s film Imitation of Life – for some time. And this one stars Lana Turner who has a fun connection to our QFS No. 150 screening of L.A. Confidential (1997).

So envelop yourself in lush color tones, sweeping music, and likely overwrought emotion for our next film, the Douglas Sirk classic Imitation of Life (1959).

Reactions and Analyses:

A girl struggling with her racial identity, trying to find acceptance and ashamed of her mother. Her mother trying to convince her that she has nothing to be ashamed of, that she is enough. Another mother striving to achieve in her profession and follow her ambitions in a competitive, ruthless industry – the cost is time with her daughter, who feels a sense of neglect when she’s older despite all the comforts the mother has provided.

These all sound like story elements for a film in 2024, and yet Imitation of Life (1959) takes on all of this. The word our QFS discussion group kept returning to was “modern.” For a film that’s 65-years old set in a very specific time, this was surprising to all of us given Douglas Sirk’s approach to filmmaking.

While the narratives within the film are modern, Imitation of Life wouldn’t be mistaken for modern in its style. The film isn’t a gritty realistic portrayal of American life in the 1950s nor does it feature Method performances that were on the rise at this time (this film is only a few years after On the Waterfront, 1954) that mirrors today’s style of acting. Instead, in Imitation of Life we quickly find the popping color of the costumes, sweeping orchestral music, theatrical lighting with brightness punctuating the darkness, Lora (Lana Turner) emerging from shadows at the exact right moment.

These are all hallmarks of melodrama, production elements intended to enhance the emotions of the scenes, to create something that’s just slightly more elevated than reality. Take just the opening sequence – it’s set on a beach in New York City. It’s clearly a stage, a clever rear projection or painted backdrop juxtaposed with the live foreground of a beach.

But we forgive this detachment from realism quickly. One member of our discussion pointed out that it’s this lack of adhering to pure realism which allows us to accept the melodrama, to allow us to be swept along with it because we don’t question as much as we would something that’s more realistic. If you’re taken up by it, you can easily forgive the somewhat flimsy setup of a woman who meets a stranger at the beach and invites her and her young child to stay the night and eventually move in. For some reason, this didn’t bother me but perhaps in a film that commits to a broader cinematic realism, I would’ve been lost right away.

This elevated reality is what serves musicals very well, and I thought immediately of Hindi cinema a.k.a. Bollywood. In Hindi films, we are keenly aware of the theatricality because, of course, people don’t break out into song in real life, strictly speaking. So the melodrama inherent in Bollywood is forgiven because the cinematic language sets up this deviation from reality.

I was also reminded of another country’s master filmmaker, Spain’s Pedro Almodovar. At QFS we watched his All About My Mother (1999, QFS No. 109) and what struck me then is that the film felt like a telenovela with its plot twists and turns. Almodovar’s mastery of balancing melodrama and realism is one of a kind and is perhaps the only filmmaker I know who’s been able to pull off authentic emotion with twisting and turning plots that defy reality.

Somewhere in the spectrum between Bollywood and Almodovar lies Douglas Sirk. More than half a century ago, Sirk uses melodrama in Imitation of Life to probe the problematic racial dynamics in his adopted country, the United States. Originally from Germany, the filmmaker fled Nazi persecution and made a career in the American movie industry. I’ve noticed that often it takes a foreign-born director to keenly see some of the divisions of America and render them into art on the screen. In college, I had a terrific course that explored America through the lens of foreign-born directors. Though Sirk wasn’t in the course, he very well could have been where he would’ve joined the ranks of Milos Forman (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 1975, QFS No. 75), fellow German émigré Fritz Lang (Fury, 1936, QFS No. 37), and Wim Wenders (Paris, Texas, 1984), among others.

One of the commonalities those directors displayed was a foreigner’s ability to both admire their new homeland and also criticize it, warts and all. Which is also a way of expressing love of their adopted country. In Imitation of Life, Sirk sees that a white person can flourish, reach their heights, seemingly on their own. But in the background, working in the kitchen unseen, is their black counterpart toiling away. Lora ascends to the top of her career while Annie (Juanita Moore) supports her faithfully.

But at what cost? Annie is unable to convince her daughter Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner) – a girl who can pass as white – that being black is nothing to be ashamed of. Perhaps the love and care she spent supporting Lora and her daughter Susie (Sandra Dee) is the cost for Annie. While Sarah Jane’s struggles are deep, existential, and wrenching, Susie’s amount to feeling as if her mother wasn’t around to spend time with her. Not to trivialize Susie’s angst, but Sirk feels like he’s making a sly commentary here. A black girl’s struggle in America is very deep and profound while a rich white girl can have the luxury of not worrying about her personal identity but instead can worry about the usual things children worry about.

What struck me throughout the film is that the characters don’t live in a time where they have language to address or understand race relations. Lora doesn’t offer meaningful support other than to suggest that things will get better. And Annie is unable to talk to her daughter about race in a nuanced or meaningful way. Of course, they are living in a time where divisions are very real between white and black families – the decision that struck down legal segregation, Brown v. The Board of Education, only happened five years before Imitation of Life was released – so it’s understandable that they don’t know how to talk about race in a constructive way. We’re still struggling with it now, but we have more language and tools. What I’m saying is: everyone in this movie would’ve benefitted from being in therapy.

For me, the entire film is worth it for this one particular payoff: the scene where Annie in essence says goodbye to Sarah Jane. Annie has discovered that Sarah Jane has moved across the country to Hollywood with a new name, working in a chorus line as an object of desire (or as lascivious a job as could be permitted to portray in 1959). Annie goes to her and is done fighting with her daughter, but instead only wants to hold her. As a final act of motherly love, she does what Sarah Jane asks – to leave her alone and pretend they aren’t related.

The hold each other and both cry in each other’s arms. The roommate enters and as Annie leaves, she tells the roommate she used to raise “Miss Linda” – Sarah Jane’s new name, tacitly acknowledging her daughter is someone else now. After Sarah Jane closes the door, she cries sans says she was raised by a “mammie” “all my life.”

It’s devastating, and I did my best to keep from crying as much as they did. Throughout the film, Annie attempts to relentlessly be a mother. And in the end, what’s the most motherly thing she could do? Set her daughter free and assure her she could come back any time and her mother would be there to love her.

The melodrama builds and crescendos to this and somehow, even though the film doesn’t adhere to strict realism in anyway, I felt like I knew these people, these characters. As an American-raised child immigrants, I too have felt in many ways the way Sarah Jane felt in the film. I didn’t want to be seen as different than the other kids at school and at times not want my parents around where my classmates could see them. Sarah Jane is mortified when her mother comes to school to bring her an umbrella, revealing to the others that she’s actually black. I can’t say that I had experiences exactly like that, but I completely understood the character’s struggle in those scenes in a deep way.

Douglas Sirk gives the heft of the narrative to this story of identity, of race, in a way that’s uniquely American, and puts the burden on Juanita Moore in a titanic performance as Annie. In a meta way, Annie, the black character, has the bigger character arc, the bigger struggle, than Lora, played by one of Hollywood’s biggest stars Lana Turner. But it’s Turner that gets top billing, gets the posters and the recognition and, of course, the money. This too is a commentary, though unintended, about America, about life, and about Hollywood. In that way, Imitation of Life penetrates on more layers than maybe it even intended.

Halfway through the film, Annie deeply knows Sarah Jane’s struggle and says to Lora, “How do you tell a child that she was born to be hurt?” To utter this in a mainstream film in 1959 is no small feat. The fact that it’s probably still relevant is the real tragedy of Imitation of Life. Yet another aspect of what a modern 21st Century film this 1959 melodrama truly is.

Godzilla Minus One (2023)

QFS No. 151 - This is the first kaiju film selected by Quarantine Film Society. Kaiju, of course, is the film subgenre in which giant monsters destroy things. I think it’s amazing that what seems like a very limited type of film has a named subgenre, but this is where I’m wrong. There are tons of these movies and television shows varying in quality in the 70 years since Godzilla (1954) came out from Japan. I’m certainly no expert on these films, but I do enjoy a good giant animal picture now and again.

QFS No. 151 - The invitation for September 4, 2024

Godzilla Minus One (2023) is the first kaiju film selected by Quarantine Film Society. Kaiju, of course, is the film subgenre in which giant monsters destroy things. I think it’s amazing that what seems like a very limited type of film has a named subgenre, but this is where I’m wrong. There are tons of these movies and television shows varying in quality in the 70 years since Godzilla (1954) came out from Japan. I’m certainly no expert on these films, but I do enjoy a good giant animal picture now and again.

Godzilla Minus One created quite a buzz last year and I really wanted to see it. I’ve heard good things about it from a filmmaking and storytelling perspective, but also in the visual and special effects. If I’m not mistaken, they had a very slim VFX team compared to say big studio movies. And yet, they took home the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, beating out a Marvel film, a Mission: Impossible film and Ridley Scott who is no stranger to Visual Effects. The first foreign language film to win the Visual Effects Oscar, which is cool.

Speaking of, this will be our fifth selection from Japan but our first Japanese film from this century. So curl with Godzilla Minus One and watch a giant lizard break things! (#spoiler) Join us next week for Godzilla Minus One.

Reactions and Analyses:

Is Godzilla’s destruction purposeful? Does he (it, she, they) know what he’s destroying? Is it intentional? Or is the destruction indiscriminate?

That was one of my main questions for the QFS discussion group and several were curious about this as well. And perhaps, for a mega-superfan of kaiju films, this is a question that’s very basic. But for someone like myself, it seemed an important question.

Perhaps the reason why I’m curious about this is that I’m not sure how to feel towards Godzilla. In some sense, if the destruction is unintentional, there’s a bit of sympathy one can feel towards the creature. It doesn’t know what it’s doing, it’s primal and a production of human tampering with nature – then it’s almost justified in its actions. A force of nature. After all, you can’t be angry with the actions of a hurricane or a volcano because it’s something unlocked by the Earth.

But if Godzilla is an avenging god, wreaking havoc on a populace already suffering from the toll of devastating global war – then, it gets a little complicated. Godzilla, portrayed for seventy years on the big and small screens, appears in Godzilla Minus One as being fueled - or at least “embiggened” - by human’s insatiable need for bigger, larger and more destructive weapons. A scene, almost a cutaway scene, depicts the US dropping experimental nuclear bombs on the Bikini Atoll – with an insert shot of an underwater monstrous eye opening and powering up. The implication is this is what humans hath wrought. Nuclear war and self-annihilation.

Or as metaphor, a giant uncontrollable lizard getting larger and larger as it destroys more and more. A stand-in for the arms race writ large.

All Godzilla films are metaphoric and perhaps cautionary, from the original 1954 version to this one in 2023, borne of post-war Japan where nuclear annihilation was not theoretical but actual. It’s astonishing to realize that only nine short years after World War II and on the heels of the nuclear bombs wiping out Nagasaki and Hiroshima, that Toho Studios would make a film about a creature that was destroying Japanese cities. I even had this feeling while watching the 2023 iteration, that these poor people had suffered enough from fire bombings and nuclear weapons – isn’t it a bit too much to also subject them to a giant destructive lizard?

Perhaps this is where cultural tastes and takes diverge between the US and Japan, which came up in our conversation. It’s easy to imagine that if the roles were reversed, that US filmmakers would very much make a film of giant monsters attacking Japan or Germany – their enemies in that war – as opposed to attaching its own populace on the shores of the Untied States . We found ourselves pondering what would’ve happened if Japanese filmmakers did indeed decide to make a 1954 film of Godzilla attacking the US, a revenge fantasy film in the way that would make the likes of a young Quentin Tarantino proud. Retribution through art is something we’ve seen before, but the Japanese have resisted that and instead turn inward with the Godzilla films.

And especially in Godzilla Minus One. Shikishima (Ryunosuke Kamiki) was a naval flyer in the war but when we discover him, he’s abandoned his duty as a kamikaze pilot honor bound to die in a suicide attack against the Allies. Although this is shameful, culturally, in 2024 looking back the filmmakers turn this around and seem to say – yes, that was your duty then, but now we need to live and build our nation. And by ejecting just before he flies into Godzilla’s mouth with his bomb-laden plane, Shikishima saves the day, lives honorably, and lives on – even rewarded by discovering that Noriko (Minami Hamabe) is still alive. So living is worth living for, you see.

The nationalistic pride in Godzilla Minus One evoked another recent film we’ve screened from another part of Asia - RRR (2022, QFS No. 86). In S.S. Rajamouli’s revisionist period piece, India is a place that had physical might and used violence and warfare to overthrow British rulers. Never mind the fact that this never happened and India is well known for its nonviolent moral and intellectual revolution that truly changed the world (as portrayed in Gandhi, 1982, QFS No. 100) – the India of 2022 is trying to assert a new world dominance. One that shows its military, technological and physical might as opposed to its intellectual and moral one from the past. RRR is a virulently nationalistic work of fiction that seeks to scrub that past and recast India as a mighty nation, ready to do battle. I, for one, found this appalling and will discuss further in the RRR QFS essay that remains TBW.

And yet, there’s a parallel we found in our discussion with Godzilla Minus One. Japan was demilitarized after World War II and there was a sentiment that they might prefer to live that way, to build their society and give up their imperialistic past. In 2024, the world is a vastly different place. With a resurgent and belligerent China at their doorstep, is Godzilla Minus One recasting Japan’s past, to show that they have might in numbers and a national pride? And that this means their love of the Japanese country fuels their current military force for good and will keep the Chinese at bay? The former soldiers in Godzilla Minus One fight not because it’s their duty as soldiers, but it is their collective duty to build a nation of people, assembling a “civilian” navy to fight an enemy at their shores. One can interpret that this is all proxy for regional domination and moral superiority over a foe, even if it’s not overt. (Though, to me and others in the group who brought this up, it feels overt.)

But while the film does have this national pride coursing through, there is ample criticism of the Japanese government. The former admiral Kenji Noda (Hidetaka Yoshioka) says:

Come to think of it this country has treated life far too cheaply. Poorly armored tanks. Poor supply chains resulting in half of all deaths from starvation and disease. Fighter planes built without ejection seats and finally, kamikaze and suicide attacks. That's why this time I'd take pride in a citizen led effort that sacrifices no lives at all! This next battle is not one waged to the death, but a battle to live for the future.

There you see this pride, but also damnation of nation’s leadership. It’s a fine line for the filmmakers to walk and they do so pretty well. Which got us to thinking – this is about as good as you can make this type of film, isn’t? The filmmakers balance politics, human drama, and action in a film about a giant lizard destroying everything in its path. There’s ample metaphor, there are emotional stakes – it all comes together in an science fiction film.

I does feel, however, of the scant Japanese Godzilla films I’ve seen, this one has taken some of the worst of American action film schlock and absorbed it, much the way Godzilla absorbs ammunition rounds. There’s the extremely cheesy lines, the overwrought emotions and overly convenient storytelling. Unfortunately, Noriko is saddled with several of these – Is your war finally over? As her first line to Shikishima when they reunite at the end feels straight out of the worst Jerry Bruckheimer/Michael Bay collaboration. Is that … Godzilla? Is one of the more useless expressions of dialogue you’ll find in a movie but it did make me laugh out loud (unintended comedy laughter is still laughter I guess). And of course, Noriko somehow survives Godzilla’s energy breath blast giving us the happy American-style (or Bollywood-style) ending we’ve come to expect with a massive film like this. Not to mention the somewhat predictable climax, where Shikishima ejects and survives as well.

Are these flaws or features? Any way you slice it, to make a film about an indiscriminate killing force that destroys on a large scale, is no small feat (pun intend… small feet… never mind). But to make it memorable, you have to make it about people, not about the lizard. And even if their emotions are not totally believable, they sure are more believable than a giant monster reigning terror across a nation. The bringing together of both make for what might just be the apex in kaiju – specifically Godzilla – movie making.

L.A. Confidential (1997)

QFS No. 150 - In 1931 and 1932, there were a few gangster pictures that helped established the genre – Little Cesar* (1931), The Public Enemy (1931) and this week’s selection Scarface (1932).

QFS No. 150 - The invitation for August 28, 2024

I’m fairly certain that everyone or nearly everyone reading this has seen L.A. Confidential, one of the great Los Angeles movies and truly a modern classic in so many ways. You’ve got a young Russell Crowe, not yet a household name, the steely-eyed Guy Pearce, Kim Basinger with probably her best performance, director Curtis Hanson’s exacting detail of the period and his fantastic adaptation of James Ellory’s period novel. And, well, okay, it does have Kevin Spacey but we don’t have to talk about that right now.

Aside from him, I’m partial to the overall excellence in the cast, which was put together by casting director Mali Finn. Mali cast L.A. Confidential and Titanic (1997), both of which came out the same year. Three years later, I moved to Los Angeles and was hired by Mali to be her assistant – my first job in the industry. To my additional great fortune, in the spring of 2001 we started work casting Curtis Hanson’s follow-up to L.A. Confidential, the Eminem-starred 8 Mile (2002). A cinephile who was closely involved with the UCLA Film & Television Archives, Curtis told us early on that he was approaching 8 Mile as a modern Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and hosted a screening of Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1978) for insight into the tone. What I’m saying is that Curtis would’ve enjoyed being a part of QFS or at least the idea of it.

Curtis, James Cameron, Joel Schumacher, Sharat Raju* and dozens of other directors loved having Mali as their casting director and she was known as a director’s casting director. She cast “real” seeming people and didn’t fall for beautiful faces, something I came to appreciate in my time working in her office alongside her. If you look at the films she worked on – and there were a lot of them – you would likely see a commonality in the actors who make up the fringes of the supporting cast. The ensemble for lack of a better term. I would argue (I mean, I have argued this point) that Titanic’s supporting cast are just as compelling as the main stars and possibly more so. That’s Mali’s fingerprints on Titanic, and you’ll be able to see that care in populating a cinematic world in this week’s selection as well.

L.A. Confidential is also part of what is truly an incredible film year, 1997. Check it out – joining this week’s film and Titanic, at the Academy Awards alone you’ve got As Good as it Gets, Good Will Hunting, Life is Beautiful and The Fully Monty hitting the big categories. Then throw in Boogie Nights, Contact, Princess Mononoke, the first Austin Powers, Jackie Brown, Men in Black, Liar Liar, Wag the Dog, The Fifth Element, Tomorrow Never Dies (the best of the Piece Brosnan Bond films?), Con Air, The Game (underrated Fincher film), Face/Off, Gattaca, I Know What You Did Last Summer, Donnie Brasco, Gross Pointe Blanke, My Best Friend’s Wedding (solid Julia Roberts romantic comedy), Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm – I mean good lord we could have a screening series just on 1997!

I remember watching L.A. Confidential in the theater before I had ever even visited Los Angeles, and loved it. I’ve rewatched the film numerous times since moving to and living in LA and there’s an additional level of enjoyment you get from seeing sites that still exist – which can be an oddity in LA – as well as areas that feel very much a part of the city's past. Curtis Hanson, a native Angeleno who was probably a child when the events of this film take place, is meticulous in his recreation of that time. The DVD (which I still proudly have on my shelf) has terrific featurettes that are basically Curtis giving a tour of shooting locations in LA and they’re bite-sized and lovely.

Our 150th selection just felt like an appropriate time to revisit this film and its cool, stylish take on 1950s Los Angeles that has the slightest of connections to yours truly. I’m looking forward to revisiting it with you all and raising a glass for crossing a new QFS milestone.

*Shameless, I know.

Reactions and Analyses:

Closer to the end of L.A. Confidential (1997), Captain Dudley Smith (James Cromwell) holds a conference with his Los Angeles Police Department officers announcing the details of the death of one of their own, Detective Jack Vincennes (Kevin Spacey) and instructs everyone to find the killer at all costs. This is all misleading, of course, since it’s Dudley himself who killed Vincennes. But only we, the audience, know that.

As the officers are filing out, he summons Detective Ed Exley (Guy Pearce) and mentions that Vincennes had a lead, and maybe it was in regards to his killer. The name, uttered in Vincennes final breath to Dudley, was “Rollo Tomasi.” The name is a fictional moniker Exley gave to the name of the man who killed his father and was never found – and only Vincennes knows about it.

It’s here that Exley now knows the truth – Dudley killed Vincennes. It’s the final piece of the puzzle that solves the Night Owl killings and answers a host of other questions for which Exley had been searching.

The shot has remained on the back of Exley’s head throughout this exchange. But once this name is mentioned, it cuts to his close up. And lingers on it – long enough for the audience to know, but we also want to know what is Exley going to do or say? It’s suspenseful, it’s tense and it’s simply a cut to a close up. Exley has to register it, decide, not betray any emotion, and come to a realization – all in a simple close up.

The next shot, it’s back to the back of his head, Dudley leaves, and Exley turns to camera, a close up again – and he’s shaken and something has changed.

It's an extraordinary moment in an extraordinary work of directing. It’s a bringing together of performance, cinematography, writing, and directing. It encapsulates what a great director does – bring together all the elements that make up a movie and synthesize them into something greater than their parts. Curtis Hanson does this masterfully throughout L.A. Confidential and re-watching the film for the seven hundredth time (give or take) gave us the opportunity to revel in the true excellence of his craft.

Perhaps it’s easy to forget that Guy Pearce and Russell Crowe (as Bud White) were total newcomers to American audiences in 1997. And take Crowe’s Bud White in Hanson’s hands as both director and writer. When I first saw the film in the theater 27 years ago, I remember loathing Bud White but also fearing him, which I think is the point. But this time, I picked up on something that might seem obvious but was new to me.

All the characters in the film are hiding something or angling for something. Dudley clearly is hiding his corruption. Exley is a climber – on the surface he’s a good cop, and truly he is. But he’s playing the angles, understanding how to get higher in the ranks. Lynn Bracken (Kim Basinger) is literally appearing to be Veronica Lake but is actually a girl from Bisbee, Arizona – and cheats on White with Exley to get Exley in trouble or killed. Pierce Patchett (David Strathairn) appears to be a businessman but he’s caught up in prostitution and drugs. The D.A. (Ron Rifkin) is a closeted homosexual. Vincennes appears slick but loathes what he does. And so on.

But the only one who is “pure,” who we can say is what you see is what you get – that’s Bud White. In a way, he’s the least corruptible. That’s not saying he’s a clean cop. On the contrary, he’s part of Dudley’s squad that beats up rival gangsters off the records. But he’s true to himself, the boy who watched his father beat his mother to death and has the physical and mental scars to prove it.

If there’s a thesis in L.A. Confidential it’s this – to have people protect us from the evils in the world, you can’t do it with just brawn and you can’t do it with just brains. You need both. So while Bud White is the brawn, he uses his brain to connect the dots and discover that his former partner Dick Stensland (Graham Beckel) lied to him and was part of a heroin racket.

And Exley, in what is probably the best glasses-wearing police officer portrayal in history, goes from what we believe is bookish, shrewd, and prestige-chasing to someone willing to plant evidence and shoot someone a fleeing suspect in the back. The very things he tells his superior, Dudley, he’s not going to do because that’s not the right way. And it’s Dudley who he shoots from behind after all is said and done.

This convergence of brain (Exley) and brawn (White), and how each transform into the other, culminates in the scene where the two nearly kill each other. Exley barges into Lynn’s home and they then have sex – but it’s all a setup with Sid Hutchins (Danny DeVito) taking blackmail photos “accidentally” given to White by Dudley so White then is driven to kill Exley. And he very nearly does until Exley reveals that he knows Dudley killed Vincennes. White, still enraged, ultimately burns off and does not go through with destroying Exley.