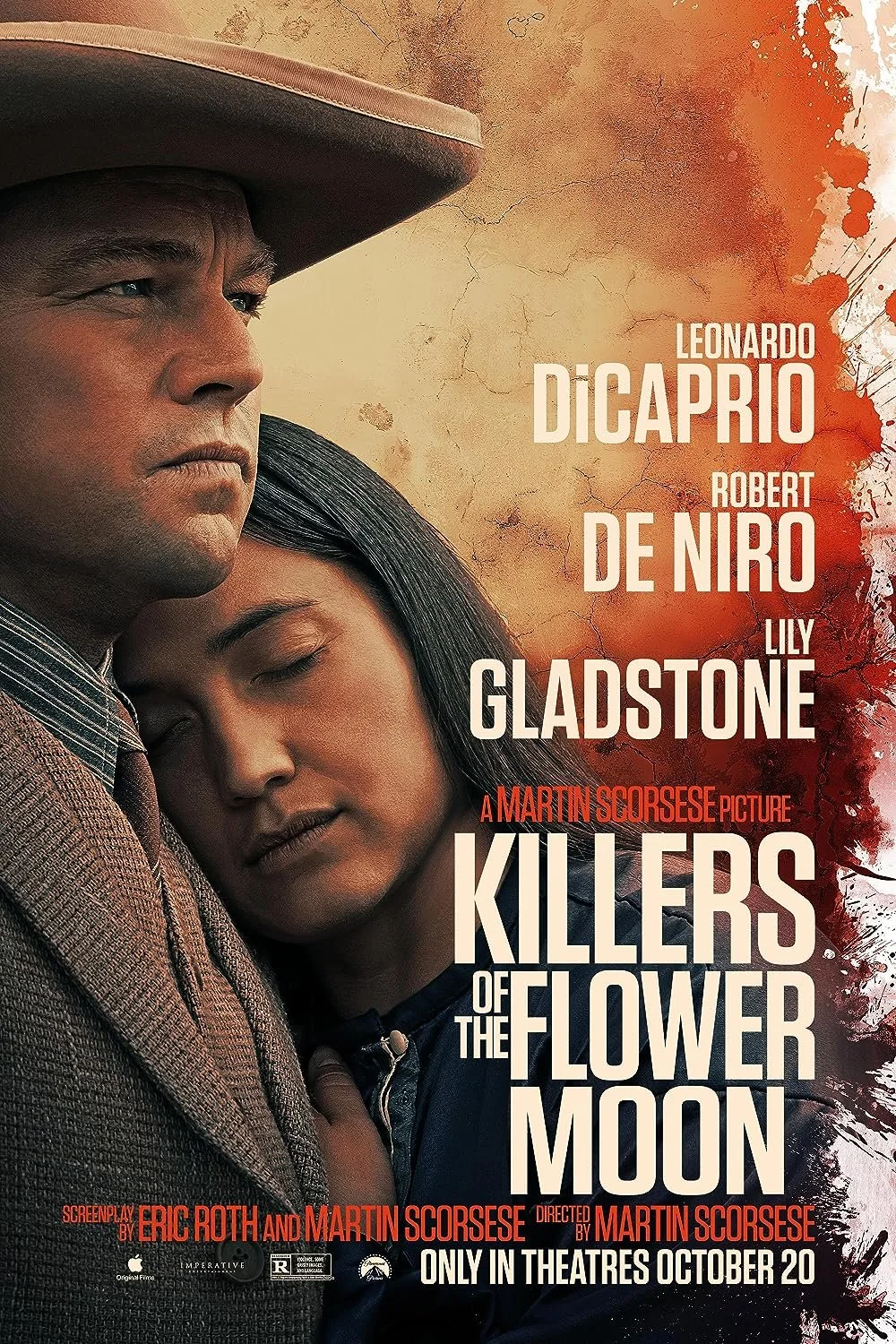

Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

QFS No. 126 - The invitation for November 1, 2023

As you all know, this is the most recent film directed by Martin Scorsese, Patron Saint of QFS. It’s his 26th feature film and our second Scorsese selection after After Hours (1985, QFS No. 85) last year. And, crucially, the first of his films made during the QFS Pandemic Era. Scorsese is about to turn 81-years old in a couple of weeks and it is entirely possible that this is his final movie. For that reason alone, it’s worth seeing Killers of the Flower Moon in the theater – the way the master undoubtedly intended.

Since I’ve already seen the film and don’t want to spoil anything, we’ll keep this week’s missive short. But do go and see the film if you can. It is, I’m sure you’ve heard, on the long side and will come in just one minute short of our longest QFS selection, Ben-Hur (1959, QFS No. 35). So get all the snacks you can gather up and go see Killers of the Flower Moon if you haven’t already!

Reactions and Analyses

This feels like both a Scorsese film and unlike a Scorsese film. There are several Martin Scorsese hallmarks throughout and echoes of films past - The Departed (2006), Shutter Island (2010), Silence (2016), I’d say even Taxi Driver (1976) to name a few - the untidy storyline, the violence, a gloom that hangs over the protagonists, a main character who’s lost and difficult to root for. The complicated morality and dilemmas faced by the characters especially the protagonist (who, maybe, is also the antagonist?). But it’s unlike a Scorsese film in that it felt like his most political, at least since perhaps The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). Political in the following sense: taking something that has an established narrative and then exploring that narrative and telling it in a radical new way. By its very nature, that new telling becomes hotly contested or protested. In The Last Temptation of Christ, he portrays Jesus Christ’s thoughts as he’s on the cross and an imagining of his own humanity in an alternate reality. The public outcry and backlash against the film has been well documented.

For Killers of the Flower Moon, here we are watching a film that explores a part of American history - the interaction between descendants of Europeans in the Americas and the indigenous people of the Americas - but not in the way that Westerns of the past characterized it. A past that’s been told one way for so long but is told here by Scorsese in almost the inverse. A true story that has been buried about a wealthy tribe bled to death - literally, and of its wealth - by the White people who were thought to be their friends and allies. And Scorsese brings it to life in a way only he can. Not to raise awareness necessarily or to make a politcal statement, but his sheer act of humanizing the Osage and this particular story seems radical to me. The casual racism and nod to white supremacy feels both on point for the time and not gratutious but also extremely upsetting and provocative at the same time. (Perhaps a little more explanation/exposition about how money was doled out to the Osage only when someone had a White sponsor would’ve been useful, but I sort of got it from the subtle dialogue and a cursory knowledge of that history.)

Initially, when the opening montage intercut with newsreels and expository title cards, I could not help but feeling struck by how little I knew about the murders of the Osage and that they were, per capita, the wealthiest people in the world at the time. It reminded me of the Tulsa race massacre in 1921 of “Black Wall Street” - a shockingly awful episode in American history I knew virutally nothing about, the horror and scope of which I didn’t fully comprehend until it was portrayed in HBO’s The Watchmen. (I’d like to point out that I believe myself to be highly educated and a student of history - and yet, here I was in the theater, my own ignorance very much exposed.) Scorsese has the Osage characters in the film worry about suffering the same fate after seeing a newsreel of the massacre. The Tulsa Massacre’s inclusion in the film by Scorsese and screenwriter Eric Roth is no accident, of course. And I know that there have been Indigenous critics who have complained about the portrayal once again of Native Americans as victims, which is a valid criticism of course. To me - these characters are portayed as humans with agency, with fears and hopes, with love and hatred. Mollie has a strong will and won’t back down (perhaps Scorsese’s strongest ever female character), heading to Washington, DC even when she can barely walk. She is the true hero of the film and acts with courage and determination even when she’s being steadily poisoned by the person who should be the closest to her - her husband. When Mollie wails after learning her child was killed in the home blast, it sent chills down my spine. Her ex-husband confesses that he’s lonely and afraid. These are primal human emotions and scenes that have been so few and far between for Native American characters in the long and troubled history of the Western in American cinema.

The group discussed the choice of storytelling. It’s been widely documented that the original screenplay focused on the nascent FBI and its investigation of the murders, with Leonardo DiCaprio playing the Tom White role. When Scorsese and Roth reconceived the script and made it into a more psychological drama by hitching it to the relationship between Mollie (Lily Gladstone) and Ernest Burkhart, DiCaprio switched roles to the more expanded one - and the most emotionally complex one, a true Scorsese protagonist.

Some brought up this alternative treatment of the story: remove the financial obstacles to making this film and the incentive to tell it through its white stars, what would’ve the story been like if it was entirely told from Mollie’s point of view? We’re with the Osage Nation and people are dying in mysterious ways. Then the FBI shows up - what would this story be like? Perhaps Scorsese isn’t the filmmaker to tell that story, or perhaps he would receive criticism for being an 80-year-old White man telling a story with Indigenous protagonists. It’s an interesting counterfactual to consider.

One of my main questions was - did Ernest love her? Some in the group speculated whether Ernest was smart enough to know what love is. Was he only in it for the money or did he develop an actual affection for Mollie? For me, I think he did love her. But he was easily manipulated. He gleefully professes his greed and love of money very early on in the film. He does terrible things and takes part in steadily killing off her family. He makes sure Mollie’s sister is buried with her jewelry just so they can rob the grave later on. And so on and so on. But when he’s on the stand and he’s torn up, his inner turmoil is apparent.

But he’s also consistently manipulated - primarily by William Hale (Robert DeNiro), later by the FBI who sweep him up and turn him into a witness without him really even seeming to understand what that means. And then even by Hale’s lawyers who almost convince him to do a total 180. Some in the QFS group argued - Ernest is not without agency. He is complict in poisoning Mollie but he could’ve chosen to not go through with it. I still think that he’s a simpleton who was conflicted but lacked courage and a backbone to do what is right. As one of the writers in our group pointed out, Scorsese doesn’t let him off the hook. Ernest doesn’t get a chance to confess, come clean, pay penance and be redeemed. That’s not Scorsese’s way - not here and not usually in any of his films. This White guy isn’t getting a pass for all the bad things he’s done because he finally does the right thing in helping send Hale to prison.

Hale is one of the more fascinating and complex antagonists portayed by DeNiro, even given DeNiro’s long career in portraying antagonists. He’s akin to the Sacklers of today - people who are on their surface philanthropists and have done good in the world, but at the same time were ruthless greed-driven psychopaths who either directly or indirectly kill people with impunity. Hale speaks the Osage language, he knows everybody in town, people love him - and yet, he’s their destroyer. It’s so good and so perfect for today and historically as well. If this is intended as a metaphor for America’s relationship with the native peoples of this continent, then it works - at least it did for me.

Lily Gladstone is unreal and should be simply handed the Oscar for Leading Actress right now. The entire cast - DiCaprio has taken on a persona I don’t think I’ve ever seen from him, with what must be a prosthetic mouthpiece for that sneer that goes along with the terrific slouch. So much conveyed in that body language, a Caliban-esque creature taking orders from DeNiro’s Propsero. DeNiro who manages to restrain his New York accent (with maybe a few times that it almost slipped out) but also restrains his performance, making it that much more powerful in portraying a White man in power who doesn’t need to raise his voice or even really do anything violent himself (other than paddle Ernest - which, I read, was an actual paddling).

The ensemble is so good it’s criminal - Jesse Plemons, John Lithgow, Brendan Fraser who just brings the heat from the moment you first see him, randomly Jason Isbell who is solid. The courtroom scenes feel almost like a second film but the tenstion and the performances are so wonderful that, for me at least, it folds right into the film as a new movement of the symphony. But special shoutout to Ty Mitchell, the dude with the cataracts in one eye (I believe that’s what he has). That guy just brings the house down - he’s so natural, so excellent, and such a lynchpin for all the bad deeds and then for all of them to come crashing down. He has loyalty to only himself but also he has blood on his hands from all he’s done, morally okay with killing if they’re “Indians.”

Lastly, we discussed, at length, that there may not be another filmmaker who, at the tail end of a long career and in old age, can still make a movie so vibrant, so new, and such a piece of film art. Who else is doing that in his 80s? Who else can make a 3-hour commercial film that’s also an artistic exploration of human greed and desire? Someone pointed out that Stanley Kurbrick — though not in his 80s when he died — chose to make Eyes Wide Shut (1999), his exploration into love, marriage, relationship, lust, desire. So vastly different than his previous work, and though imperfect, has many of the hallmarks of Kubrick’s lifetime of creation. The parallels between that and Scorsese’s work here are spot on, in my opinion.

Late career artistic magic - who else? Perhaps Ingmar Bergman? Steven Spielberg? Akira Kurosawa? Scorsese’s last few films are as follows: The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), Silence, The Irishman (2019) and now Killers of the Flower Moon. Those four films would be considered masterpieces in a lot of other careers. For Scorsese, those may not crack the top ten of his best films - though I would argue that his latest does. He’s truly a national treasure and this film was more than worthy of inclusion in the legacy he’ll leave behind as a filmmaker. A legacy still unfinished, I hope. I’m not yet prepared to have seen the final Scorsese film.