The Seed of the Sacred Fig (2024)

QFS No. 168 -The Seed of the Sacred Fig has been on my list since I saw a riveting trailer and have read a little bit about the film. Shot in secrecy in Tehran, this will be our second film from Iran, after the terrific A Separation (2011, QFS No. 49), directed by Asghar Farhadi.

QFS No. 168 - The invitation for March 5, 2025

The Seed of the Sacred Fig (2024) has been on my list since I saw a riveting trailer and have read a little bit about the film. Shot in secrecy in Tehran, this will be our second film from Iran, after the terrific A Separation (2011, QFS No. 49), directed by Asghar Farhadi. A Separation and his following one The Salesman (2016) both won the Academy Award for Best International Film, making Farhadi the only filmmaker from the Middle East to direct an Oscar-winning film in this category – and he did it twice.

The Seed of the Sacred Fig could’ve made Mohammad Rasoulof the second filmmaker to do so, but I’m Still Here (2024) took home the prize this year. Still, looking forward to seeing this our second selection from Iran (via Germany) - join the discussion!

Reactions and Analyses:

The idea of Chekov’s gun – that if you see a gun at the beginning of the story you need to see it be fired later on – is what appears to be the initial setup of The Seed of the Sacred Fig (2024). The very first shot are bullets being dropped onto the table and a gun handed to its new owner, Iman (Missagh Zareh). Moments later, it’s on the passenger seat as Iman drives away, the camera tilting down to reveal it, overtly drawing out attention to the weapon.

But for so much emphasis on the gun and the thriller-style opening of the film, the gun ends up being only a very small part of the film for the entire first half – so much so that it’s almost forgotten, the way Iman inadvertently forgets it in the bathroom until his wife Najmeh (the incredible Soheila Golsestani) discovers it one day. She’s already let him know that she’s not thrilled with having a gun around. But what we don’t yet realize is that this is all a long setup by filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof for a payoff later on. What we learn later is that the gun is more than a gun in this present-day Iran – it’s a symbol. It represents state power, and Iman will be a proxy for the people who wield that power.

To get there, the filmmaker focuses on the very real protests of 2022 unfolding in Iran with women standing up to the country’s misogynistic totalitarian regime, refusing to wear hijabs and standing up to the very real possibility of harm and death. In The Seed of the Sacred Fig set against this backdrop, Iman, an investigator trying to climb the ranks within the government, discovers in his new role that he’s supposed to rubber stamp death warrants without really looking into their veracity. He’s not thrilled about compromising his morals and is caught in a bind, and Najmeh talks him through his obligations. This, too, seems like a setup by the filmmakers about a man with a moral dilemma.

Their two young daughters, one a college student, Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and the other Sana (Setareh Maleki), a teenager, are firmly in the crosshairs of the forces of change roiling their city and country Najmeh tells her children that they must dress modestly and avoid any hint that they are anything other than rule abiding because her father’s promotion depends on it – though they don’t know exactly what their father does. And besides, they’ll get government housing if he’s a judge and they’ll each have their own rooms.

But the forces of the world can’t be kept out because of social media. And here, the filmmakers are very inventive (perhaps too much?) with their use of real-life footage posted online at the time. The government was able to control their people in darkness, but with the light of videos and media, it’s a different story. Sadaf (Niousha Akhshi), Rezvan’s friend, is injured at a protest, shot in the face with buckshot. Secretly brought into their home, bleeding, Najmeh – despite very vocally opposing the protests and the women involved – patiently removes each pellet from Sadaf’s face. It’s a wrenching, horror-filled scene told in two close ups with the music rising, tight shots of bullets being removed cut with the mother’s stricken face, holding back tears. This is textbook in visualizing a character’s turning point – we see it in Najmeh’s face: this could’ve been her daughter.

She’s not all the way convinced the protests are good, but she knows that even innocent women – children – are caught in the crossfire. Later, the girls find out that Sadaf is taken away after she returned to college but nobody knows where she is. And Najmeh tries to get information covertly from Iman, without betraying that it’s someone they know for fear of getting him into trouble. She seeks out a family friend, Fatemeh (Shiva Ordooie) for information through Fatemeh’s husband who also works for a secret faction of the police.

And throughout all this, Najmeh’s concern remains mostly domestic. Her husband works too much and she pleads with him that her daughters need their father, especially now. He reveals that the arrests have escalated so much that he’s up all day rubber stamping guilty confessions.

Finally, the family is able to sit down and have dinner, but it leads to an inevitable explosive fight. The girls know what’s happening through social media, through the injury to Sadaf, that the people who might be injured are innocent and their lives are being destroyed just because they don’t want to wear the veil. Iman says they are misled by people with ill intentions, by women - whores, he believes - who want to walk around naked on the streets. The fight is vicious and ends with Najmeh firing back at the girls we finally had a dinner together and you ruined it.

All this time – the gun is not even remotely a part of the story. In fact, the entire QFS discussion group forgot its existence by and large except as an accessory carried by Iman. So when the gun disappeared, it truly was a surprise as much as it was a mystery. Iman can’t find it and Najmeh scramble to locate it. The children never even knew the gun was in the house, but they become Iman’s the primary suspects.

And it’s at this point the film kicks into overdrive and leaves the outside world’s tumult and brings it inside. Consumed by paranoia and fear of being imprisoned for his negligence, it’s a riveting next hour or so – in part because we really have no idea who could have taken the gun. Several of us believed he must’ve just lost it, which is set up nicely by the filmmakers as mentioned earlier when the overworked Iman accidentally left it with his clothes on the laundry hamper.

Instead of accepting that he could’ve possibly made a mistake, Iman assumes his family must’ve taken the gun. It’s unfathomable that someone in his position could do something in error, so he turns his ire and focus on the family. He makes Najmeh search the children’s room, turning everything inside out. She thoroughly searches the home and cannot find it. Iman begins to unravel and follows his colleague’s suggestion to have his children professionally interrogated by their mutual friend Alireza (anonymous actor). When you have your children professionally interrogated, you may have gone past the point of no return.

And in many ways, he has. The interrogator is certain it’s Rezvan, the college student. But she vehemently denies it. Further escalating Iman’s paranoia is that protestors have been finding people who work for the regime in secret and posting their names and addresses online – which is what happens to Iman. His colleague suggests he leaves with his family for a few days, is given a backup gun, and decides to go to his ancestral home. But before that, he drives home in a terrific sequence that showcases Iman’s paranoia. Everywhere he looks he thinks people are following or watching him. He looks over at a young woman driving next to him without a hijab and notices her small neck tattoo – is she one of these loose women, one of his enemies? A motorcycle seems to be driving a little too close – is that someone following him or is it just normal traffic? He gets home and sees someone on a cellphone outside their apartment building – is that someone keeping tabs on him, or is he waiting for a friend?

Iman is forced to experience life the way people without power live under the totalitarian regime of the country. The filmmaker has cleverly set this up throughout the film with echoes of Brazil (1985, QFS No. 158) or George Orwell’s dystopian 1984 as unavoidable comparisons. The state can turn on one of its own; no one is safe from the state’s mindless cruelty. And all of this seems like it’s going in that direction– a story about a man who is part of the system becomes a victim of that very system, leading him to question the system itself and his place within it, to perhaps renounce or even move to transform it.

That is not what Rasoulof does. Iman still convinced that one of his family took the gun and the final portion of the film devolves into a chaotic madman, unable to love his own family any more, becomes the cruel embodiment of the country’s leadership, still convinced that one of the three women in his life have stolen the gun. And in fact, one has! The one no one suspected, the younger daughter Sana. But Iman doesn’t know that yet, which makes for more suspense. After running two people who have recognized him off the road, the family arrives at the abandoned, dusty desert homestead of his youth where he locks the family in a room until they come out and reveal who has the gun. It escalates with Iman locking all of them in the room – except Sana who has escaped with the gun.

And there it has returned, Chekov’s gun, waiting to be fired. The final chase, though perhaps longer than it ought to be and slightly illogical, is still suspense filled and in a great location that evokes the longevity of Iran and Persia – something older than the mores of the current Iranian regime. Sana has the gun and Iman, who has another gun, chases her with the two others scrambling. I found myself wondering what is the desired outcome here? I don’t want Iman to be shot and killed, but I don’t want the women to suffer either. But what then? It makes for great drama that ends with Sana unable to shoot Iman except into the ground at his feet, where her father then collapses under the ancient sand walkway and is swallowed by the land itself.

Though Rezvan and Sana are Iman’s flesh and blood, he has become unable to see them as such in this final sequence, only concerned about his own ambition and safety. He seems prepared to kill his daughter Sana, even taunting her that she doesn’t know how to shoot. The filmmakers have chosen to have Iman embody the state – he is modern Iran’s government, unmoved and unwilling to bend.

It's a choice that feels like perhaps more symbolism than rooted in reality. Would a father actually do that? Would he forsake all of his memories, his love for his wife, seeing his children grow, all of their history together, because he’s been blinded by power and control? The filmmakers seem to say, yes, this is what totalitarianism does to ordinary people. Iman is the state and the state can only be eliminated, not changed – that’s what the director seems to be saying

Rasoulof can’t be faulted for any of these choices. After all, he’s been a victim of the regime for what appears to be his entire adult life. Much has been made about the fact that he filmed this movie entirely in secret over a 70-day period, and had to escape the country to arrive at the Cannes Film Festival for the premiere. So when we criticize the excessive chase sequence at the end or the imperfections in the conclusion of the film – aren’t the women now in even more danger and will be heavily questioned about the whereabouts of their dead husband/father? – all of this might have to be taken with a grain of salt (sand?).

What an extraordinary feat of pure will to make this film under circumstances we, living in the West, couldn’t possibly imagine. Sure there are a handful of plot holes, including how did Sana know there was a gun in the house and where it was and how did she hide it during the search, but as a group most of us found ourselves easily forgiving much of this given the larger scope of the film and the extreme lengths Rasoulof went to make it.

His filmmaking is incredibly savvy, using real footage shared on social media with even a nod to YouTube as a way to learn about all things, including how to load and fire a gun. This element of the old Iranian overlords unable to contain the new information-laden world is a fascinating additional angle to both The Seed of the Sacred Fig and the true protests that swept the nation in 2022 and beyond. For Rasoulof to pull all of this off in a contained thriller, a family social drama, and a commentary on society, the film is an extraordinary piece of filmmaking – both creatively and production-wise. While everyone might not agree on the story and ideas contained within the film itself, it’s hard not to take inspiration from the execution and commitment to telling a story like this against all the unimaginable odds to do so.

The Brutalist (2024)

QFS No. 167 -The Brutalist will be our longest QFS film selection, a full three minutes longer than Ben-Hur (1959, QFS No. 35).

QFS No. 167 - The invitation for February 26, 2025

The Brutalist will be our longest QFS film selection, a full three minutes longer than Ben-Hur (1959, QFS No. 35). That’s right, this three-hour-and-thirty-five-minute nominee for Best Picture rivals last year’s Killers of the Flower Moon (2023, QFS No. 126) for length, coming at just nine minutes longer. I’m in for it! It’s time to separate the wheat from the chaff! Who of you will ride with me off this cinematic cliff into the great glorious unknown?!

And by that I mean – watch The Brutalist this week and discuss it with us in a civilized manner.

Reactions and Analyses:

We’ve seen countless films detailing the horrors of the Holocaust and mass genocide of the Jewish people enacted by the Nazi regime in Germany in the early 20th Century. From true first-hand accounts to artistic recreations, the depths of human cruelty and the bravery of those who were able to survive or help others survive have been portrayed in every genre over the previous 70 years or so. In fact, a couple decades ago, Adrian Brody, star of The Brutalist, previously played Wladyslaw Szpilman, the true story of a survival and heavily influenced on director Roman Polanski’s own escape from Poland in The Pianist (2002) a couple decades ago.

Rarely, however, do films portray what happens afterwards, how someone attempts to live after surviving such horrors. The messy reintroduction into society having lost everything but his or her own intelligence and wits. One of our QFS discussion group members brought this up in our conversation, that The Brutalist chronicles what comes after. And while the film isn’t any one thing, we discovered, the aftermath of trauma is perhaps the most predominant thread of a big epic film that lacks a clear single theme.

The film begins at this point, at the what-happens-afterwards moment. In one of the more extraordinarily beautiful shots from a film filled with them, the camera finds Brody’s Laszlo Toth in the dark, awaken in second sequence of the film. The shot is handheld, messy, with lots of people in darkness and scattering of light between him and the camera as a woman in voice over dictates a letter written to Toth. We follow him through the ambiguous space – is this a prison camp? – through the chaos and uncertainty, until he bursts through a door and light floods in as the brassy fanfare from the score explodes, and Laszlo, giddy with joy, grasps a friend and they celebrate in Hungarian, looking up. It’s an electrifying way to start a film.

Above the new immigrants, as if from their perspective, looms the Statue of Liberty, sideways. It’s an angle rarely scene, evoking the arrival of the Italian immigrants to America in The Godfather Part II (1974). But this is different – the iconic symbol of freedom is askew. Perhaps the filmmaker Brady Corbet suggests that this new home will be a complicated, contradictory place. Freedom, yes, but also hardship.

Throughout the film, there is a sense that immigrants and those on the margins built America, but what thanks do they get? They are Jews and are tolerated – a line overtly stated by Harry Lee (Joe Alwyn), the wealthy benefactor Harrison Lee Van Buren’s (Guy Pearce) son. Tolerated, but barely.

Laszlo and his cousin Attila (Alessandro Nivola), hired by Harry to secretly rebuild his father’s library, are thrown out when Harrison comes home to find this modernist, minimalist room Laszlo created. Harrison shouts at them, berating that he’s out front with his his mother who is sick and comes home to find the construction mess outside and, gasp, a black man is on the grounds as part of the working crew. Harrison tosses the Hungarians out. But later, a fancy design magazine deemed the new library an artistic masterpiece forcing Harrison track down Laszlo to apologies. The wealthy American hires the immigrant Hungarian to build a massive monument and center in honor of his later mother. (A woman who wasn’t fond of Blacks apparently. If only could’ve known that a Jew is building a sanctuary in her honor.)

But even then, Harrison has to hire a second designer – Jim Simpson (Michael Epp), a Protestant to appease the community – as a check against Toth’s expensive artistry and to make sure that a Christian is involved. The “consultant” second guesses the Hungarian immigrant throughout and in response, Toth belittles Jim’s work designing shopping malls.

This is only one thread of the film, the experience of immigrants in post-war America, and interwoven with it are the power dynamics between art and money, between Toth and Harrison. Harrison, mercurial but seemingly supportive of Toth, funds his massive project that Toth designs. He even introduces Toth to his personal lawyer Michael Hoffman (Peter Polycarpou), a fellow Jew who helps Toth bring his wife Erzsebet (Felicity Jones) and niece Zsofia (Raffey Cassidy) to immigrate to the US so they can be reunited.

Even there, power dynamics take lead – the powerful and connected can work the immigration system because they have access to lawyers and are valued for their creations. But the laborers who build these buildings will find no such help. Harrison trusts Toth, but also knows he can never be loved or as talented as immigrant artist. He says as much to Toth in what is probably one of the least graphic but most disturbing rape scenes. While at the stunning Carrara, a massive ancient marble excavation site in Italy, the two have been drinking and Toth has been using heroin to feed his addiction. They’ve wandered away from a party in the marble caves when Harrison rapes Toth in a wide shot, silhouetted, without seeing the expression of either and only hearing Harrision’s tauns. The scene serves as an overt metaphor of exploitation by the rich that wasn’t necessarily needed according to many in our group. The film clearly shows Harrison having power over Toth and the wealthy exploting the artist was crystal clear already. This extreme act drives it home in a way that was both over-the-top and perhaps unnecessary. Nevertheless, it's part of the story – Toth is raped by Harrison, just as the natural marble of Italian mountainside has raped by humans for centuries.

Toth is an imperfect protagonist, perhaps permanently scarred by surviving a genocide, quoted by Zsofia later in the film as having said, “No matter what the others try and sell you, it is the destination, not the journey.” Apt, for someone who experienced what we assume he experienced, as we encounter him in this what-comes-after phase of his life. We find him addicted to pain killers and eventually heroin, with which he nearly kills Erzsebet by giving her too much to help her with the pain that has rendered her unable to walk easily.

In one of the many beguiling aspects of the film, here’s another one - is this entire tale told through the eyes of his mute niece Zsofia? The opening scene is her being interrogated by unseen officers, a character we don’t yet know and are unsure of anything beyond the questions being asked of her that she doesn’t answer. And in the end, a retrospective of Toth’s work in 1980 is being narrated by an older Zsofia now speaking fluently at the Venice Biennale of Architecture. There are several aspects of The Brutalist that feel frustrating, but perhaps the end is the most glaring. Throughout, I was curious why - why was this style of art and architecture developed? The answer is given to us in this Venice lecture, not visually or through the narrative of the film. Grown Zsofia explains that Toth and others from the Brutalist movement took the grim, brutal reality of the Holocaust, of the unfeeling grey walls of concentration camps, and repurposed it, filling spaces with life and hope as opposed to death and horror. He does to Harrison earlier on in the film, this somewhat thesis:

“Nothing is of its own explanation. Is there a better description of a cube than that of its construction? There was a war on. And yet it is my understanding that many of the sites of my projects have survived. They remain there still in the city. When the terrible recollections of what happened in Europe cease to humiliate us, I expect for them to serve instead as a political stimulus, sparking the upheavals that so frequently occur in the cycles of peoplehood. I already anticipate a communal rhetoric of anger and fear. A whole river of such frivolities may flow undammed. But my buildings were devised to endure such erosion of the Danube's shoreline.”

Would’ve been nice to have Toth actually, you know, display that artistry in the film. His eloquent explanation about the enduring nature of physical buildings aside, we are only told of the reasoning behind the Brutalist style in an overt scene expository concluding seminar. For a visually stunning film this is a decidedly un-visual conclusion.

The Brutalist is not any one thing. Epic in scope – perhaps worth watching for the score and Lol Crawley’s VistaVision cinematography alone – it seemingly is an immigrant tale. Or maybe it’s a story of art versus commerce. Or maybe it’s about the building of America on the backs of the downtrodden. Or maybe it’s about the creation of Israel, which pops up from time to time. Or maybe it’s all of those or none of those. Is this a good thing or a bad thing? Films can be ambiguous, of course, and the filmmaker has made it clear in his public statements that he believes film should require you to think, to engage, to find meaning for yourself. And for that, The Brutalist definitely succeeds.

Nickel Boys (2024)

QFS No. 166 - Here’s what I know about the film – Nickel Boys is based on a Colson Whitehead book, who is an author I tell people I’ve read but actually I have only had his Underground Railroad on my list for nearly a decade. And that concludes my knowledge of Nickel Boys.

QFS No. 166 - The invitation for February 19, 2025

I know even less about Nickel Boys than perhaps any of the other nominees. Which is exactly why I want to see it.

Here’s what I know about the film – Nickel Boys is based on a Colson Whitehead book, who is an author I tell people I’ve read but actually I have only had his Underground Railroad on my list for nearly a decade. And that concludes my knowledge of Nickel Boys.

Join us to discuss this blank slate of a film (at least for me) as we continue to watch the Oscar Nominees for Best Picture this year!

Reactions and Analyses:

As a filmmaker, one of the most powerful tools you can use is the point-of-view shot. The POV allows the director to put the audience in the perspective of the main character or to experience the scene through one person versus the other. Whose scene is it was the most common question asked of us in film school.

At the American Film Institute, where several of us in the QFS discussion group attended graduate film school, they hammer home this idea, that the film is told through someone. Scenes, which may have more than one protagonist (or antagonist, for that matter), must still be told to someone. These rules can be broken, of course, but the POV shot is one of the important concepts that separates film from stage and other forms of visual art.

Nickel Boys (2024) takes this idea to the extreme. The film is told entirely through a character’s perspective, through POV shots, and never deviates. There are no shots, nothing we experience in the film that is not from the point of view of one of our main characters. Even the still cutaways or stock footage-like vignettes are the imaginations of Elwood (Ethan Herisse). If you wanted to split hairs about it, there are a few moments when we’re behind our main character, seeing the back of his head. But the effect is the same - we are living this story with him.

The “him” changes, though. What appears to be Elwood’s story becomes also Turner’s (Brandon Wilson) story. At first, this feels sudden and not exactly with any real purpose. The addition of Turner’s perspective begins when Elwood and Turner meet, now at the brutally abusive Nickel Academy reform school, in a pretty ordinary school lunchroom scene. After nearly half the movie as Elwood, we now experience the the film through two pairs of eyes, which gives us the additional benefit of seeing Elwood and Turner instead of only through reflections.

Later on in the film, the real reason to add Turner’s perspective is revealed - they become the same person. Turner, who survives and escapes Nickel Academy, runs to Elwood’s grandmother Hattie (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor) and informs her that her grandson Elwood was shot and killed in a field. Distraught, Turner and Hattie embrace which kicks off one of the most overwhelmingly emotional montages I’ve ever seen on screen. Intercut with black-and-white footage that feels like it’s from the slavery era, featuring White men on horseback hunting down “fugitive” Black people, we see old footage of a young Elwood, disappearing from each shot. One moment he’s on screen, the next, in the exact same frame, he’s gone. Blinking away, like a ghost, like he never existed. This all aligns with the terrible experience of Nickel Academy itself - kids would routinely just “disappear,” the administrators of the school claiming that the children ran away. When instead they were killed and buried and forgotten. I’m reminded of Ralph Ellison’s seminal work Invisible Man in which the Black first-person protagonist may as well be invisible by a cruel and indifferent society.

But wait - in Nickel Boys’ well-timed flash-forward sequences, aren’t we with a grown-up Elwood? Didn’t he survive? No, it turns out that Turner has assumed Elwood’s identity after escaping and surviving and traveling north to New York in the decades since his traumatic childhood at Nickel. It’s a remarkable and completely unexpected twist, but it also serves as a message about commonality and shared trauma. An absorbing of experiences between the two boys. Their unity after Elwood’s death is in a way making whole something that was severed and ripped away from these boys - a normal upbringing and childhood.

One person in our group brought up the unrelenting injustice of it all, and how it felt unfair and unjust - there was no way out. Especially for Elwood, who was hitchhiking and became an innocent passenger in what turned out to be a stolen car, ends up paying for something he didn’t do. Ultimately, paying with his life. While alive, he was the one attempting to expose the brutality of Nickel, only to have his life cut down by the very people running the place. It’s all incredibly unfair, and that’s the point the film illustrates. The injustice of growing up Black in America - specifically in the timeframe of the film, but also today. One scene in particular illustrated the filmmaker’s point of view on this, it seems to me. The kids are preparing for a sanctioned boxing match for the White kids of Nickel Academy and Griff (Luke Tennie) is their big fighter. Elwood and Turner overhear the head teacher Spencer (Hamish Linklater) tell Griff to throw the fight, to intentionally lose in the third round (turns out the White administrators put money on this fight). If Griff loses, the Black kids will be subjected to a year’s worth of ridicule until the next annual match. If he doesn’t, then perhaps Griff will suddenly disappear. He certainly will face truly brutal punishment, as was portrayed earlier in the film’s most truly horrifying sequence in which Elwood is tortured by his “teachers” in a sweaty room that feels like a slaughterhouse.

In the fight, there is no victory for Griff. He ultimately, accidentally, wins the match, and pleads with Spencer that he didn’t know what round it was, all while his classmates surround him in celebration. But in the center of their jubilation, he is remorseful and horrified. It’s heartbreaking, because we as an audience know what will happen to Griff - and it does. He’s “disappeared” and becomes one of the dozens who were killed an buried in unmarked graves, only to be uncovered a generation later with modern DNA testing and investigative journalism, including work done by (what turns out to be) grown “Curtis” Elwood (who was actually Turner).

The film devastated me, as I know it did for several in our group. Why, when other films have portrayed this era, was this even perhaps more heartbreaking? The answer lies in part due to the style of the film. From the very beginning, we see the world through someone’s eyes and only through their eyes. They (we, therefore) look up at an orange, dangling from the tree, in the first shot of the film. You soon realize that the film’s aspect ratio is 4.3, which is a square and not often used in modern cinema. But its affect is to make us feel as if we’re seeing something closer to natural human vision, not the cinematic widescreen movies to which we’ve become accustomed. This isn’t a movie but someone’s life and we are living within it. We’re actually seeing life through another’s eyes. And the initial images are the very details that stick in your mind as a child - close up on a glass, a glimpse of your mother as she leaves the room, the playing cards being shuffled, tinsel dropped down onto your face from the Christmas tree. Low angles, looking up at the world.

We stay in this perspective, never seeing “us” - the person through whom we’re experiencing the film - except in reflections, such as in his (our) grandmother’s iron as it travels back and forth on the ironing board, or a storefront window. This relentless commitment to pure POV, purely seeing the story through someone’s eyes, forces us to be in their shoes. Director RaMell Ross and cinematographer Jomo Fray keep us in this exhausting, taxing world with glimpes of beauty in between the darkness. And throughout, an extraordinary attention to the detail of life.

This is all to ask the question - is this the best way for us as a modern audience in the 21st Century to experience life in the Jim Crow segregation-era south, artistically? I argue that it is. Film is, if nothing else, the greatest empathy device every created. You live through someone’s experience in any film told well when using all the tools of cinema in a way to enhance the storytelling. In Nickel Boys, the filmmakers chose to mostly use only one tool - the POV - arguably the medium’s most powerful one to extraordinary affect. And the result is nothing short of an immersion, a disappearing into the life of one (two) boys who live through horror but throughout are able to find beauty, friendship, and ultimately, a measure of justice.

A Complete Unknown (2024)

QFS No. 165 - Mangold, of course, is no stranger to big name music icon biopics, having directed Walk the Line (2005), the solid film about the life of Johnny Cash. That film earned Reese Witherspoon an Oscar for portraying June Carter Cash and a nomination for Joaquin Phoenix in the title role. Fast forward twenty years later and Timothee Chalamet is nominated for Best Actor with Edward Norton and Monica Barbaro getting nominations in the supporting categories.

QFS No. 165 - The invitation for February 12, 2025

Is A Complete Unknown this year’s Elvis (2023)? No, of course not, because for one thing, it’s about Bob Dylan and not Elvis Presley. Also, this week’s film is directed by James Mangold, who is a very very different filmmaker than Baz Luhrmann is so many ways. First, they spell and pronounce their names differently, which is how you know they are different people. Second, Mangold is an American while Luhrmann is from Australia, two entirely different places. And third, Mangold is about as mainstream, down-the-line filmmaker as we get these days – which is something that you wouldn’t say about Luhrmann. When you want a film that hits all the marks but might not push the envelope too much, you hire Mangold. This generation’s Chris Columbus (the filmmaker, not the explorer), or, perhaps, Ron Howard.*

Mangold, of course, is no stranger to big name music icon biopics, having directed Walk the Line (2005), the solid film about the life of Johnny Cash. That film earned Reese Witherspoon an Oscar for portraying June Carter Cash and a nomination for Joaquin Phoenix in the title role. Fast forward twenty years later** and Timothee Chalamet is nominated for Best Actor with Edward Norton and Monica Barbaro getting nominations in the supporting categories.

So let’s continue our march to watching all the Best Picture nominees and discussing a few of them between now and the end of the month! Get out to the theater and see A Complete Unknown and join the discussion!

*No disrespect intended. Hit singles and doubles consistently and you’re in the Hall of Fame.

**What?! Twenty years since Walk the Line?

Reactions and Analyses:

Perhaps it only has to be about the music.

This was a sentiment shared by a few of us discussing A Complete Unknown (2024). James Mangold, a solid, steady filmmaker, didn’t fall into the standard clichés of the biopic – including the clichés to which he was susceptible in his Walk the Line (2004) musical biopic two decades ago. In that, the roots of Johnny Cash’s music are explained. His childhood, his loneliness and drug use, depression and ultimately redemption – all of it captured as a cause, a wellspring for his music. It’s the “Rosebud” effect, a childhood trauma that explains an adult’s life.

A Complete Unknown skips all of that. We know very little about Bob Dylan (Timothee Chalamet) as he arrives in the folk-rock scene of New York City in the early 1960s and right away he spins beautiful poetry as he sings to his hero, the bed-ridden Woody Guthrie (Scoot McNairy). We don’t see Dylan being directly inspired by the world around him except for one civil rights rally he attends and current events unfolding in the background - but he must be inspired by the world because his music speaks to the time and tumult of the era. We don’t see his writing process or how he develops his poetry, but it comes to him and he writes it without struggle. He is a conduit from on high, the filmmakers appear to be saying.

And yet, the movie is enjoyable, pleasant, and inoffensive throughout. Perhaps all you need is (a) legendary music by the only Nobel Prize-winning American songwriter in history and (b) utterly fantastic performances by great actors. Without exception, the cast is stunning and the fact that they play their own instruments and sing is even more astonishing.

Narratively though, there is no specific central tension of the film. Dylan doesn’t struggle with depression or doubt, though he does try the patience of those around him. Joan Baez (Monica Barbaro) and Sylvie Russo (Elle Fanning), both lovers, both find him to be kind of a jerk (to paraphrase them). He’s not a tortured artist, but he’s a selfish one - an enigma as you’d expect from a demigod. Dylan expresses the belief that music is music, it doesn’t need to be put into a category or sanctified, which is how he finds himself up against folk music establishment, including his early mentor Pete Seeger (Edward Norton).

It's that tension between innovation and tradition that is almost at the center of the film. “Almost” because it’s not overtly the driving central narrative of the film, but an undercurrent that culminates in the well-known Newport Folk Festival in which “Dylan Goes Electric.” And here, the filmmakers attempt to create a dramatic conclusion of the film, exaggerating history for dramatic effect. Which is fine – filmmakers often bend real events to fit the narrative of a biopic. But the culmination, the climax is somewhat affixed at the end as opposed to building towards it.

And they can’t be blamed. With all of Bob Dylan’s music at the fingertips of the filmmakers and all the artistry and poetry contained in Dylan’s words, a film about his life and ascent to the apex of American music and culture doesn’t have to be more than a celebration of the music and a nostalgic portrayal of a turbulent time in history. The film only spans four or five years of Dylan’s life and we know almost as much about him at the end as we did the beginning. A Complete Unknown is, therefore, an apt title – he remains an enigma and the film doesn’t strive to demystify him. Music comes to him as visions to an oracle, it seems. A telling line in the film, one of the most effective, is spoken by Dylan after getting punched in the face at a bar and arrives a his ex-girlfriend Sylvie’s home. He says, “Everyone asks where these songs come from, Sylvie. But then you watch their faces, and they're not asking where the songs come from. They're asking why the songs didn't come to them.”

This is the closest the film gets to an insight or reflection of Dylan. Is the answer it came to him because he is sent from the heavens? It’s as plausible an explanation in this narrative.

One other scene gives us an insight into Dylan as a person. It’s the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis when all of New York is panicking with nuclear war possibly looming. But Dylan, instead of preparing to flee as Joan Baez is, instead plays music in the basement of the folk bar, railing against the idiocy of global war. The world might end, but to him it’s only about the music. These two scenes are the closest Mangold gets to probing the soul of Dylan.

The scenes lack visual dynamism or real cinematographic artistry. Which is the polar opposite of last year’s celebrated biopic of another American groundbreaking legend of music and culture, Elvis (2023). In that film, Baz Luhrman uses frantic, manic, expressionistic mayhem to bring music and the Elvis Pressley experience to visual life. In that way, Elvis more about the filmmaking than it is about Elivs, you could argue. Contrast A Complete Unknown with this or something like Whiplash (2014), in which Damien Chazelle brings music and the experience of playing music to life visually. Or even 8 Mile (2002), where Curtis Hanson portrays the life of a young musician who finds inspiration for his music from the immediate world around him, and also a glimpse into how he crafts the music – writing, rewriting, testing.

Dylan, in Mangold’s hands, does none of that. He arrives in the film a phenomenon and remains one. Dylan inherits mantle of the folk masters and their tradition of speaking truth to power on behalf of the undercast, then removes folk music from the dustbowl into the mainstream and ultimately electrifies it. Is it all planned out by a god from on high? It feels that way in A Complete Unknown.

But perhaps that’s all it needs. Perhaps it just has to be about the music.

Conclave (2024)

QFS No. 164 - It’s that time again – time to cram in a bunch of Academy Award nominees! Personally, I’m going to attempt to watch all of the Best Picture nominees before the broadcast on March 1st.

QFS No. 164 - The invitation for February 5, 2025

It’s that time again – time to cram in a bunch of Academy Award nominees! Personally, I’m going to attempt to watch all of the Best Picture nominees before the broadcast on March 1st.

This selection was made by throwing a dart a dartboard, metaphorically. I haven’t seen a majority of this year’s Best Picture nominees so might as well start somewhere. Is Conclave the most interesting of the bunch? Who knows!

So join us in watching our first film from 2024 and discuss below!

Reactions and Analyses:

For a (literal) closed-room thriller, one moment in Conclave (2024) stands out as an outlier and punctures the closed box in which much of the movie is contained. The Dean of the College of Cardinals and man in charge of the vote for the new Pope, Lawrence (Ralph Finnes), finally follows his heart and casts a vote not for himself but for Benitez (Carlos Diehz) to become the leader of the Catholic faith. The moment Lawrence delivers his vote, an explosion rocks St. Peter’s Cathedral and light finally enters the building. The scene stands out in part because it’s incredibly dramatic – the most action in the entire film – but also because it conveys a message.

And that message from Conclave seems clear: spiritual faith does not happen in a box. Modern religion requires the leaders of that faith to be out in the world. The real world is out there and it will invade and burst through, so you might as well deal with it directly. It’s not an accident that turtles appear in the film, a creature that can put its head in its shell and insulate itself from the world.

Benitez’s stated mission is decidedly the opposite. We discover that his life as a priest has been in the trenches as a secret archbishop in Kabul and other hotspots around the world. He toiled with the people and gives a speech that states his personal thesis, which is also the film’s thesis:

No, my brother. The thing you’re fighting is here… inside each and every one of us, if we give in to hate now, if we speak of “sides” instead of speaking for every man and woman. Forgive me, but these last few days we have shown ourselves to be small petty men. We have seemed concerned only with ourselves, with Rome, with these elections, with power. But things are not the Church. The Church is not tradition. The Church is not the past. The Church is what we do next.

Conclave on its surface is about religion – and, yes, it is of course because it takes place in the highest realm of the Catholic church. But in essence, the film is about politics. Without squinting all that much, you can see the film is speaking to our time, right now, in this world. Petty men and power, feckless liberals trying to hold off a radical conservative takeover, someone who wants to make the church great again, when meanwhile the world is burning outside. Tedesco (Sergio Castellitto), the Italian cardinal, decries the liberal march the church has taken over the last 60 years. If the clergy were all still speaking Latin – which they were before the Vatican II reforms from 1962-65 – everyone would be united instead of going off to seek their own countrymen or language groups, as they do in the Vatican cafeteria, he points out. And also, for good measure, in the next breath he exposes his personal racism and bigotry by stating to Lawrence that he couldn’t possibly imagine the disgrace of having a brown or black Pope (though, one would argue, people in populations with mostly brown and black people are often the strongest Catholic countries so that is indeed the face of the faith…).

But even the middle-of-the-road cardinals can’t get their act together, unable to find a leader to satisfy all tastes. The moderate, Tremblay (John Lithgow) is proven corrupt, having bought votes which is a grave sin for a priest in the Catholic tradition. Ultimately, it’s Benitez, an outsider with a pure heart who convinces them that he’s the true voice of the people, in part by saying he doesn’t want to become Pope or the trappings of power. If anything, Conclave is a story about dysfunctional political systems.

It’s also a story the distance between lived faith and institutional faith. With few exceptions, there is very little discussion about religious doctrine. And the men, for the most part, don’t appear to be running to be the next Pope for any honorable or noble reasons, but a need for power or to prevent someone else from obtaining it. Lawrence himself states repeatedly and openly that he does not want to be Pope and very nearly left the clergy. But his homily in which he extolls the virtue of doubt just before the conclave begins inspires several cardinals to vote for him instead of Bellini (Stanley Tucci), which throws the plan of the liberal faction into disarray. As someone in our QFS group put it, these are not gods or special people, just ordinary people put in positions of power.

And what ordinary people do can sometimes be messy, which is in part why this film is so thrilling. Edward Berger, who directed the excellent All Quiet on the Western Front (2022) is an exacting filmmaker. His percussive score helps drive the suspense, but Berger’s visual framing that enhance the film. The compositions are stately and tightly composed, very little camera movement except when absolutely necessary. The rigidity of the framing reflects the rigidity of the Vatican, one of the world’s great seats of power. And with it, the lighting at times evokes the great Renaissance masters including Caravaggio. There’s lovely synergy between the visual references this film suggests and knowing that the Roman Catholic church was perhaps the greatest sponsor of art in Europe and likely throughout the world.

For all of the pomp and global interest in selecting a new Pope, the film feels small and therefore thrilling. Lawrence breaks into the deceased Pope’s quarters, breaking a wax seal, to investigate Tremblay’s possible malfeasance. The scene had me on the edge of my seat and really all the scene consists of is one man breaking a rule in order to weed out a larger problem. But even here, Bellini breates Lawrence and commands him not to reveal Tremblay’s problems because they need to vote for him, because this is war – and the conservative Tedesco will win if Tremblay is eliminated. Lawrence takes a principled stand and, with the help of Sister Agnes (Isabella Rossellini), prints out the documents for all the cardinals to see. And here again, the film is not about religion but about politics. About doing what is perhaps expedient but morally questionable versus doing what is noble and right but perhaps could lead to bad consequences.

In the end, it’s Benitez, the outsider who earns the most votes and becomes the new Pope. And the twist is he is neither man nor woman – someone who is as God made them. He’s the first Pope (as far as we know) to have female reproductive organs. Is this the way the Catholic church will finally have female clergy? And here is another statement by the filmmakers, and arguably this is the one that contains the most spirituality. Perhaps the best person to lead the faith is someone pure of heart, who knows true suffering and what humanity needs in organized religion. That faith is in the world – someone who is neither man nor woman, not from the old world but something new. That the church has to live, as he says in the film, in the future.

Godzilla Minus One (2023)

QFS No. 151 - This is the first kaiju film selected by Quarantine Film Society. Kaiju, of course, is the film subgenre in which giant monsters destroy things. I think it’s amazing that what seems like a very limited type of film has a named subgenre, but this is where I’m wrong. There are tons of these movies and television shows varying in quality in the 70 years since Godzilla (1954) came out from Japan. I’m certainly no expert on these films, but I do enjoy a good giant animal picture now and again.

QFS No. 151 - The invitation for September 4, 2024

Godzilla Minus One (2023) is the first kaiju film selected by Quarantine Film Society. Kaiju, of course, is the film subgenre in which giant monsters destroy things. I think it’s amazing that what seems like a very limited type of film has a named subgenre, but this is where I’m wrong. There are tons of these movies and television shows varying in quality in the 70 years since Godzilla (1954) came out from Japan. I’m certainly no expert on these films, but I do enjoy a good giant animal picture now and again.

Godzilla Minus One created quite a buzz last year and I really wanted to see it. I’ve heard good things about it from a filmmaking and storytelling perspective, but also in the visual and special effects. If I’m not mistaken, they had a very slim VFX team compared to say big studio movies. And yet, they took home the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, beating out a Marvel film, a Mission: Impossible film and Ridley Scott who is no stranger to Visual Effects. The first foreign language film to win the Visual Effects Oscar, which is cool.

Speaking of, this will be our fifth selection from Japan but our first Japanese film from this century. So curl with Godzilla Minus One and watch a giant lizard break things! (#spoiler) Join us next week for Godzilla Minus One.

Reactions and Analyses:

Is Godzilla’s destruction purposeful? Does he (it, she, they) know what he’s destroying? Is it intentional? Or is the destruction indiscriminate?

That was one of my main questions for the QFS discussion group and several were curious about this as well. And perhaps, for a mega-superfan of kaiju films, this is a question that’s very basic. But for someone like myself, it seemed an important question.

Perhaps the reason why I’m curious about this is that I’m not sure how to feel towards Godzilla. In some sense, if the destruction is unintentional, there’s a bit of sympathy one can feel towards the creature. It doesn’t know what it’s doing, it’s primal and a production of human tampering with nature – then it’s almost justified in its actions. A force of nature. After all, you can’t be angry with the actions of a hurricane or a volcano because it’s something unlocked by the Earth.

But if Godzilla is an avenging god, wreaking havoc on a populace already suffering from the toll of devastating global war – then, it gets a little complicated. Godzilla, portrayed for seventy years on the big and small screens, appears in Godzilla Minus One as being fueled - or at least “embiggened” - by human’s insatiable need for bigger, larger and more destructive weapons. A scene, almost a cutaway scene, depicts the US dropping experimental nuclear bombs on the Bikini Atoll – with an insert shot of an underwater monstrous eye opening and powering up. The implication is this is what humans hath wrought. Nuclear war and self-annihilation.

Or as metaphor, a giant uncontrollable lizard getting larger and larger as it destroys more and more. A stand-in for the arms race writ large.

All Godzilla films are metaphoric and perhaps cautionary, from the original 1954 version to this one in 2023, borne of post-war Japan where nuclear annihilation was not theoretical but actual. It’s astonishing to realize that only nine short years after World War II and on the heels of the nuclear bombs wiping out Nagasaki and Hiroshima, that Toho Studios would make a film about a creature that was destroying Japanese cities. I even had this feeling while watching the 2023 iteration, that these poor people had suffered enough from fire bombings and nuclear weapons – isn’t it a bit too much to also subject them to a giant destructive lizard?

Perhaps this is where cultural tastes and takes diverge between the US and Japan, which came up in our conversation. It’s easy to imagine that if the roles were reversed, that US filmmakers would very much make a film of giant monsters attacking Japan or Germany – their enemies in that war – as opposed to attaching its own populace on the shores of the Untied States . We found ourselves pondering what would’ve happened if Japanese filmmakers did indeed decide to make a 1954 film of Godzilla attacking the US, a revenge fantasy film in the way that would make the likes of a young Quentin Tarantino proud. Retribution through art is something we’ve seen before, but the Japanese have resisted that and instead turn inward with the Godzilla films.

And especially in Godzilla Minus One. Shikishima (Ryunosuke Kamiki) was a naval flyer in the war but when we discover him, he’s abandoned his duty as a kamikaze pilot honor bound to die in a suicide attack against the Allies. Although this is shameful, culturally, in 2024 looking back the filmmakers turn this around and seem to say – yes, that was your duty then, but now we need to live and build our nation. And by ejecting just before he flies into Godzilla’s mouth with his bomb-laden plane, Shikishima saves the day, lives honorably, and lives on – even rewarded by discovering that Noriko (Minami Hamabe) is still alive. So living is worth living for, you see.

The nationalistic pride in Godzilla Minus One evoked another recent film we’ve screened from another part of Asia - RRR (2022, QFS No. 86). In S.S. Rajamouli’s revisionist period piece, India is a place that had physical might and used violence and warfare to overthrow British rulers. Never mind the fact that this never happened and India is well known for its nonviolent moral and intellectual revolution that truly changed the world (as portrayed in Gandhi, 1982, QFS No. 100) – the India of 2022 is trying to assert a new world dominance. One that shows its military, technological and physical might as opposed to its intellectual and moral one from the past. RRR is a virulently nationalistic work of fiction that seeks to scrub that past and recast India as a mighty nation, ready to do battle. I, for one, found this appalling and will discuss further in the RRR QFS essay that remains TBW.

And yet, there’s a parallel we found in our discussion with Godzilla Minus One. Japan was demilitarized after World War II and there was a sentiment that they might prefer to live that way, to build their society and give up their imperialistic past. In 2024, the world is a vastly different place. With a resurgent and belligerent China at their doorstep, is Godzilla Minus One recasting Japan’s past, to show that they have might in numbers and a national pride? And that this means their love of the Japanese country fuels their current military force for good and will keep the Chinese at bay? The former soldiers in Godzilla Minus One fight not because it’s their duty as soldiers, but it is their collective duty to build a nation of people, assembling a “civilian” navy to fight an enemy at their shores. One can interpret that this is all proxy for regional domination and moral superiority over a foe, even if it’s not overt. (Though, to me and others in the group who brought this up, it feels overt.)

But while the film does have this national pride coursing through, there is ample criticism of the Japanese government. The former admiral Kenji Noda (Hidetaka Yoshioka) says:

Come to think of it this country has treated life far too cheaply. Poorly armored tanks. Poor supply chains resulting in half of all deaths from starvation and disease. Fighter planes built without ejection seats and finally, kamikaze and suicide attacks. That's why this time I'd take pride in a citizen led effort that sacrifices no lives at all! This next battle is not one waged to the death, but a battle to live for the future.

There you see this pride, but also damnation of nation’s leadership. It’s a fine line for the filmmakers to walk and they do so pretty well. Which got us to thinking – this is about as good as you can make this type of film, isn’t? The filmmakers balance politics, human drama, and action in a film about a giant lizard destroying everything in its path. There’s ample metaphor, there are emotional stakes – it all comes together in an science fiction film.

I does feel, however, of the scant Japanese Godzilla films I’ve seen, this one has taken some of the worst of American action film schlock and absorbed it, much the way Godzilla absorbs ammunition rounds. There’s the extremely cheesy lines, the overwrought emotions and overly convenient storytelling. Unfortunately, Noriko is saddled with several of these – Is your war finally over? As her first line to Shikishima when they reunite at the end feels straight out of the worst Jerry Bruckheimer/Michael Bay collaboration. Is that … Godzilla? Is one of the more useless expressions of dialogue you’ll find in a movie but it did make me laugh out loud (unintended comedy laughter is still laughter I guess). And of course, Noriko somehow survives Godzilla’s energy breath blast giving us the happy American-style (or Bollywood-style) ending we’ve come to expect with a massive film like this. Not to mention the somewhat predictable climax, where Shikishima ejects and survives as well.

Are these flaws or features? Any way you slice it, to make a film about an indiscriminate killing force that destroys on a large scale, is no small feat (pun intend… small feet… never mind). But to make it memorable, you have to make it about people, not about the lizard. And even if their emotions are not totally believable, they sure are more believable than a giant monster reigning terror across a nation. The bringing together of both make for what might just be the apex in kaiju – specifically Godzilla – movie making.

20 Days in Mariupol (2023)

QFS No. 135- Long time QFS members know that we rarely select documentary films due to a long-standing bias against them within the ranks of our QFS Council of Excellence. This is only our third documentary selection.

QFS No. 135 - The invitation for March 13, 2024

Long time QFS members know that we rarely select documentary films due to a long-standing bias against them within the ranks of our QFS Council of Excellence. This is only our third documentary selection. The other two – Honeyland (2019, QFS No. 5) and Flee (2021, QFS No. 69) were also both nominated for Best Documentary Feature at the Academy Awards, with Honeyland taking the prize in the 2020 Covid year Oscars. Flee did not win, but was the first film ever to be nominated for both Best Documentary Feature and Best Animated Feature – a feat which is still pretty astonishing. It remains one of my personal favorite films of the decade.

What both those films had in common were that although documentary films, they felt as if they were scripted narrative features. Honeyland followed an old lady in Macedonia harvesting honey the old-fashioned way as if it was a scripted movie, in a sense. Flee also had a scripted animated feature film feel – both because of the story of the protagonist’s life and the masterful manner in which it was told.

Which brings us to 20 Days in Mariupol (2023) – a documentary which will likely have a similar narrative action film feeling. The story was introduced to me last year by my brother who sent me this link to an Associated Press story by and about AP journalists trapped in Ukraine as the Russians invaded. They had been reporting from the battlefield and soon discovered that they were also being hunted. As most of you know, my brother is a journalist and he first learned of this incredible story while serving on a committee that selected these reporters for an award. Of course upon reading the story myself, I immediately knew this was a movie and started to look into whether the rights were available. Little did I know that the documentary was being finalized with footage from the frontlines by the journalists themselves. A movie, in some fashion, was already in the works.

The story is incredible and let me give you the lede right here: “The Russians were hunting us down. They had a list of names, including ours, and they were closing in.”

If that’s not the way to begin a great story – on screen or in print or otherwise – then I don’t know what is. The fact that it’s also a true story and one that we can watch, well I think we ought to do that.

Reactions and Analyses:

What can a documentary do that a scripted feature film cannot? This is one of the questions that went through my mind as I watched 20 Days in Mariupol (2023) and one of the first aspects of the film we discussed. In a narrative film, even a bleak film featuring war, desperation, doom and destruction all around – you would be hard pressed to find a movie that didn’t have some inkling of hope. Some path to escape, at least, if not victory outright for the protagonist.

In a documentary, however, there’s no expectation that you will receive that olive branch or lifeline from the filmmaker. The film can be as relentless as it needs to be because this is real. In a feature film, the filmmakers would (rightly?) be trashed for putting the audience through something relentlessly harrowing. In a documentary, you can turn that feeling into something like a duty to watch it. Because providing witness is what the filmmakers are hoping for in showcasing it for an audience.

One in our group put it that way – it felt like our duty to watch 20 Days in Mariupol. In part because the filmmaker-journalists made it their mission to make sure the world knew what was happening in Mariupol. Going into this film, I had some knowledge of what the filmmakers went through, having read the Associated Press reporting and also the story of the filmmakers being personally targeted by the Russian troops. I expected the filmmakers to include themselves in the storytelling, much in the way The Cove (2009) did – also an Oscar winner for Best Documentary Feature – as someone in the QFS group brought up that parallel.

Refreshingly, the filmmakers of 20 Days in Mariupol did not give in to making the film about themselves beyond what was necessary to tell the story. Although Mstyslav Chernov’s voice guides us in voiceover, the camera is never turned inward. He reflects on occasion about being Ukrainian and there are artistic vignettes of a hand covered in sand and images of his children playing in safety, for example. But they are, thankfully, very few and used at just the right times and just the right ways to break up the constant movement and bloodshed we witness on screen.

To that point, another in our group brought up the moments where the filmmaker sits down, camera still rolling, and we see a hallway sideways or the ground, not focused on anything in particular. The filmmaker catches his breath, taking in the horror and pausing from showing more if it. The moments are needed relief and are a fascinating way of involving the filmmaker in the story in a subtle way. An editor and director could have easily cut those parts out as they don’t advance the “story” or any narrative, but keeping those moments in both help to humanize our filmmaker guides through the film but also to emphasize that we are in this with them – experiencing this with them.

One member of the group mentioned that we never see the filmmaker’s face (until the very end). And yet, we are riveted – we want him to survive. He is us. In that extraordinary action sequence when they have to escape the occupied city with a Ukrainian special strike force, the filmmaking is as good as any you’ll see in a modern war film or a video game. We’re running, we see the soldier in front of us talking when paused around a corner, we dive when an airplane screams overhead. We’re on the edge of our seat, wondering how the filmmaker will survive. And yet – we’ve never seen his face.

That’s a pretty remarkable feat. Perhaps it’s because it is us. We are looking and experiencing the world with this filmmaker and exclusively through his eyes throughout – which is perhaps another thing documentary does that a feature film wouldn’t be able to get away with necessarily. Not seeing the protagonist at all and playing the film entirely through point of view is a hallmark of “documentary style” but often you see clever ways a narrative filmmaker will at least give us a glimpse of the person holding the fictitious camera. But in the documentary, we don’t see the person holding the camera, favoring instead the horror but not in a gratuitous way – it’s real, seen how a person would. At times directly, at times looking away, searching for something else but drawn back to the calamity. The blood, the babies dying or living, the people grieving the death of a child or other family member. We experience it in what feels like real time through the filmmaker’s eyes.

And finally – since this is such a recent war, one still going on, there are so many elements that make it feel truly “modern.” There’s the mission to get internet. Seeing the dozens of power strips so people can charge their phones just to use them as flashlights. The familiar buildings (e.g. Crossfit gym!) being used as shelters or bombed out malls. And then, the entire social media storyline in which the Russians accuse the reporters of faking the bombed out maternity ward and using crisis actors. “Fake news,” if you will. History isn’t just written by the victors, it’s being written in real time – as one of our QFSers put it.

In Chernov’s Academy Award just a few days ago, he said:

“But I can't change history, I can't change the past, but we are all together, you and I, we are among the most talented people in the world. We can make sure that history is corrected, that the truth prevails. And so that the people of Mariupol who died and those who gave their lives will never be forgotten. Because cinema shapes memories, and memories shape history."

Chernov’s use of footage he shot which then later appears as news footage in television programs around the world is incredibly effective in so many ways, but in one way in particular. It reminds us that one of the main driving narrative thrusts of the film is we need to get the story to the world. To prove it happened and so no one forgets. The fact that it was real, that it was a documentary, makes it more urgent for the filmmakers to share it and for the world’s eyes to see it. They got it out to the world and we’ve seen it. We were witness and it was, indeed, a duty to help shape memories and history.

Past Lives (2023)

QFS No. 134 - What I know about this film approaches zero. I do know it’s from South Korea and that it’s Celine Song’s first film after being a staff writer on a major Amazon series. So, you know – pretty amazing, that!

QFS No. 134 - The invitation for February 28, 2024

What I know about this film approaches zero. I do know it’s (partly) from South Korea and that it’s Celine Song’s first film after being a staff writer on a major Amazon series. So, you know – pretty amazing, that!

But I’ve deliberately kept myself away from knowledge of the plot and was looking forward to seeing the film. This is our second selection from South Korea, the other being Bong-Joon Ho’s Memories of Murder (2003, QFS No. 112), and many more remain on my to-watch list. The South Korean film industry just keeps blasting home runs all over the place.

Join us this week if you can!

Reactions and Analyses:

There’s a shot in Past Lives (2023) that essentially tells the premise of the film in one frame. It’s early on, Na Young says goodbye to Hae Sung because her family is immigrating from South Korea. The goodbye is curt and without over-wrought emotion because, well, they’re adolescents.

Then they each walk towards their own homes – Na Young upwards on the right of the frame and Hae Sung on the left, more or less straight, away from us. This image defines, in some ways, their trajectories. It’s simple and straightforward but clear. And it definitely sets a course for the split in their lives.

When I first selected Past Lives, knowing very little about the film besides its accolades and that it’s Oscar nominated for Best Picture, I assumed this was a South Korean film. And after having seen it, I can say that it’s very much an American film, an immigrant’s tale. This splitting or fracturing of a life in divergent storylines. It could’ve been told from my parents’ perspective leaving India in the 1970s.

I brought this up in our QFS discussion and the others pointed out that this is not just an immigrant’s tale – this is the story of anyone who is forced to split from their home at a young age and has that fondness, that nostalgic remembrance, and that powerlessness to stop that fracturing the familiar. The fact that this is also true and valid illustrates how universal and accessible the story is.

Past Lives makes an argument for the simple film told with tenderness but with just the right amount of layering. The Korean concept of “in-yun” – the layers of interaction between throughout past lives – feels deliberate beyond how it’s used to describe the relationship between Hae Sung (Teo Yoo) and Na Young/Nora (Greta Lee). Perhaps in-yun is also meant to convey that the film is not as simple as it seems, that it’s layered in unseen ways (which, I’m sure, is me misinterpreting the definition of in-yun but bear with me). That there’s depth between these two childhood friends (sweethearts?) and when they reconnect later in their lives, that connection has meaning beyond how it’s been set up in the film.

The QFS group was split on the strength of this connection. For some, the childhood connection between Na Young/Nora and Hae Sung didn’t suggest a deeper connection later in life. For example, Nora claims to not exactly remember the boys name while talking on the phone with her mother, but then discovers he’s been asking about her whereabouts for a little while now.

For others in our group, their connection in childhood was enough and felt familiar – this idea of two lives, connected through family, culture, and yes, love – two people diverging but when they reconnect, it’s fated they are to be together. Or, more specifically, in-yun. Case in point: your enjoyment of this film is directly related to whether or not you believe that their relationship at the beginning is strong enough that they could reconnect so quickly over such a long span of time.

Past Lives has the ease of a simple film well told but some of the trappings of a first-time filmmaker, several of us felt (including me). For example, there’s a scene where Nora’s (non-Korean) husband Arthur (John Magaro) talks about how they met and became a couple and moved in together and got married so she could get a green card, etc. What’s missing in his description is “love.” The kind of standard American relationship story devoid of cinematic spark or romance, but realistic and familiar. He continues to then say that in this version of the story, Hae Sun – the childhood lover – returns to her life and she realizes that this is who she should’ve been with her whole life. That he, Arthur, is the villain in this story. Hae Sun is more closely suited to her culturally but also very satisfying narratively. Both Nora and Arthur are writers so this aligns with their story-telling impulses.

Now, that’s all true but … we know that already as an audience. The filmmaker seemingly hasn’t trusted us to put that all together and she has a character explain it to us. This, to me, is a significant misstep in a story otherwise hewing close to cinematic realism. The scene, also, continues and Arthur says he started to learn Korean because Nora was talking in her sleep but in Korean. He says “You dream in a language I can’t understand. It’s like there’s this whole place inside you I can’t go.”

That is beautiful. It’s poetic, it speaks to the character himself, to their relationship, to the thrust and import of that scene. The scene could have very easily started here and it would have spoken volumes. But instead we get the needless explainer. And the ending as well – there’s a version of the film that ends as soon as Hae Sung leaves, wondering if this life is actually a past life and “we are already something else to each other in our next life? Who do you think we are then?”

Again – this is beautiful poetry. One member of the group suggested that ending of the film would be stronger if it ended right here, or right after this and he gets in his airport ride and goes. Instead of the long walk with Nora back to her husband where she cries. (And this is where I offered the additional criticism of staying in a wide shot instead of seeing her face here, for that felt like a payoff to me.) Even the opening shot - there’s an unseen bar patron watching the three in the bar. We push in slowly but instead of trusting the images of these three, with only their expressions and body language to inspire our curiosity, we’re hearing a bar patron who we will never see give us a setup that our eyes would have given us without the help.

Perhaps. These are all counterfactuals and there’s an argument in conducting film criticism that one needs to focus on the film in front of them and not the alternate version in our heads. Yes, valid – but still, the fact that these questions arise are less about how we would’ve done it differently and more about a few small weaknesses in an otherwise solid, simple film.

Despite some first-time filmmaker criticisms, there are a lot of beautiful uses of visual storytelling throughout - including the use of symmetry across eras between Na Young and Hae Sung.

And in defense of the simple film – I mean “simple” not that it lacks depth or intelligence. Quite the opposite. When the filmmaker has trusted us, we’ve filled in the blanks and walked in the shoes of two people different than ourselves and went on a journey with them. As one person in our group remarked – it’s refreshing to have a film that’s only about 90-minutes, has a simple but tender story, well-acted and executed, that brings up emotions in a natural way. Not overwrought or excessive or gratuitous. (Counterexamples from this award season include Oppenheimer, 2023 and Killer of the Flower Moon, 2023). I believed I added “inoffensive” as a way of describing Past Lives and, once again, I meant it as a compliment. There are no subplots, no side character, no stretching for meaning. It’s all there. Simple.

Whether that simplicity was effective or not, we all were in agreement, however, on this one thing – we are grateful that a movie like this is still being made, is receiving accolades, and that a lot of people have watched and enjoyed it. So consider this an endorsement of the simple film.

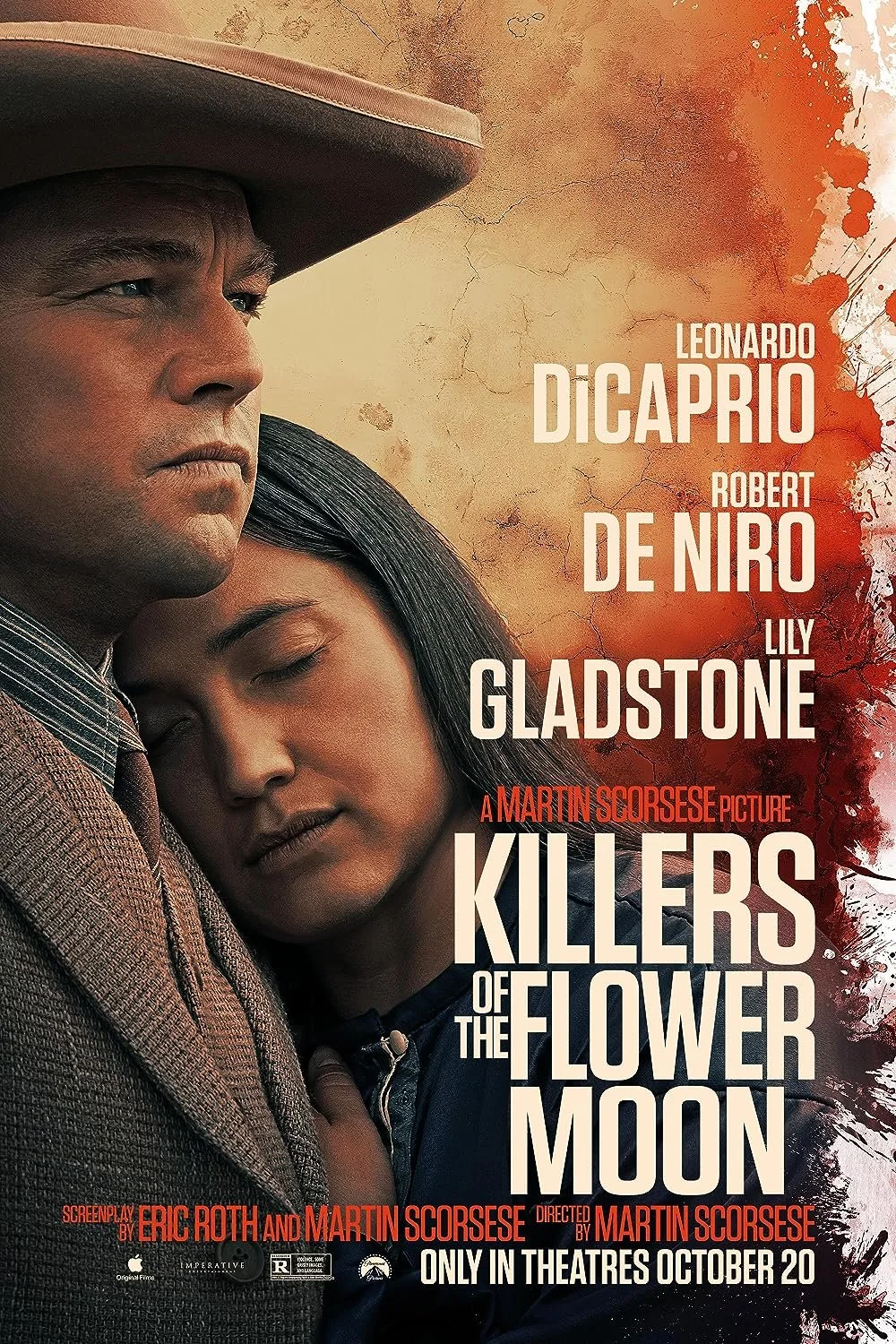

Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

QFS No. 126 - As you all know, this is the most recent film directed by Martin Scorsese, Patron Saint of QFS. It’s his 26th feature film and our second Scorsese selection after After Hours (1985, QFS No. 85) last year. And, crucially, the first of his films made during the QFS Pandemic Era. Scorsese is about to turn 81-years old in a couple of weeks and it is entirely possible that this is his final movie.

QFS No. 126 - The invitation for November 1, 2023

As you all know, this is the most recent film directed by Martin Scorsese, Patron Saint of QFS. It’s his 26th feature film and our second Scorsese selection after After Hours (1985, QFS No. 85) last year. And, crucially, the first of his films made during the QFS Pandemic Era. Scorsese is about to turn 81-years old in a couple of weeks and it is entirely possible that this is his final movie. For that reason alone, it’s worth seeing Killers of the Flower Moon in the theater – the way the master undoubtedly intended.

Since I’ve already seen the film and don’t want to spoil anything, we’ll keep this week’s missive short. But do go and see the film if you can. It is, I’m sure you’ve heard, on the long side and will come in just one minute short of our longest QFS selection, Ben-Hur (1959, QFS No. 35). So get all the snacks you can gather up and go see Killers of the Flower Moon if you haven’t already!

Reactions and Analyses

This feels like both a Scorsese film and unlike a Scorsese film. There are several Martin Scorsese hallmarks throughout and echoes of films past - The Departed (2006), Shutter Island (2010), Silence (2016), I’d say even Taxi Driver (1976) to name a few - the untidy storyline, the violence, a gloom that hangs over the protagonists, a main character who’s lost and difficult to root for. The complicated morality and dilemmas faced by the characters especially the protagonist (who, maybe, is also the antagonist?). But it’s unlike a Scorsese film in that it felt like his most political, at least since perhaps The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). Political in the following sense: taking something that has an established narrative and then exploring that narrative and telling it in a radical new way. By its very nature, that new telling becomes hotly contested or protested. In The Last Temptation of Christ, he portrays Jesus Christ’s thoughts as he’s on the cross and an imagining of his own humanity in an alternate reality. The public outcry and backlash against the film has been well documented.

For Killers of the Flower Moon, here we are watching a film that explores a part of American history - the interaction between descendants of Europeans in the Americas and the indigenous people of the Americas - but not in the way that Westerns of the past characterized it. A past that’s been told one way for so long but is told here by Scorsese in almost the inverse. A true story that has been buried about a wealthy tribe bled to death - literally, and of its wealth - by the White people who were thought to be their friends and allies. And Scorsese brings it to life in a way only he can. Not to raise awareness necessarily or to make a politcal statement, but his sheer act of humanizing the Osage and this particular story seems radical to me. The casual racism and nod to white supremacy feels both on point for the time and not gratutious but also extremely upsetting and provocative at the same time. (Perhaps a little more explanation/exposition about how money was doled out to the Osage only when someone had a White sponsor would’ve been useful, but I sort of got it from the subtle dialogue and a cursory knowledge of that history.)