Imitation of Life (1959)

QFS No. 152 - Director Douglas Sirk’s name is synonymous with melodrama. As someone who studies film and works in entertainment, this is one of those givens you know about even if you don’t know his movies.

QFS No. 152 - The invitation for September 25, 2024

Director Douglas Sirk’s name is synonymous with melodrama. As someone who studies film and works in entertainment, this is one of those givens you know about even if you don’t know his movies. I first learned about Sirk when Todd Haynes’ Far From Heaven (2002) hit the theaters. When it came out, Haynes made it clear it was an homage to Douglas Sirk films, in the story, the time period, and the style of the filmmaking.

Sirk, a Danish-German filmmaker was one of the many artists forced to flee persecution from the Nazis in the 1930s, just as Fritz Lang and Billy Wilder had to in the same era. Sirk made several German films before leaving the country and even directed short films into the late 1970s long after retiring from Hollywood filmmaking. I’ve been eager to see one of the classic Sirk melodramas – All that Heaven Allows (1955), Written on the Wind (1956), and this week’s film Imitation of Life – for some time. And this one stars Lana Turner who has a fun connection to our QFS No. 150 screening of L.A. Confidential (1997).

So envelop yourself in lush color tones, sweeping music, and likely overwrought emotion for our next film, the Douglas Sirk classic Imitation of Life (1959).

Reactions and Analyses:

A girl struggling with her racial identity, trying to find acceptance and ashamed of her mother. Her mother trying to convince her that she has nothing to be ashamed of, that she is enough. Another mother striving to achieve in her profession and follow her ambitions in a competitive, ruthless industry – the cost is time with her daughter, who feels a sense of neglect when she’s older despite all the comforts the mother has provided.

These all sound like story elements for a film in 2024, and yet Imitation of Life (1959) takes on all of this. The word our QFS discussion group kept returning to was “modern.” For a film that’s 65-years old set in a very specific time, this was surprising to all of us given Douglas Sirk’s approach to filmmaking.

While the narratives within the film are modern, Imitation of Life wouldn’t be mistaken for modern in its style. The film isn’t a gritty realistic portrayal of American life in the 1950s nor does it feature Method performances that were on the rise at this time (this film is only a few years after On the Waterfront, 1954) that mirrors today’s style of acting. Instead, in Imitation of Life we quickly find the popping color of the costumes, sweeping orchestral music, theatrical lighting with brightness punctuating the darkness, Lora (Lana Turner) emerging from shadows at the exact right moment.

These are all hallmarks of melodrama, production elements intended to enhance the emotions of the scenes, to create something that’s just slightly more elevated than reality. Take just the opening sequence – it’s set on a beach in New York City. It’s clearly a stage, a clever rear projection or painted backdrop juxtaposed with the live foreground of a beach.

But we forgive this detachment from realism quickly. One member of our discussion pointed out that it’s this lack of adhering to pure realism which allows us to accept the melodrama, to allow us to be swept along with it because we don’t question as much as we would something that’s more realistic. If you’re taken up by it, you can easily forgive the somewhat flimsy setup of a woman who meets a stranger at the beach and invites her and her young child to stay the night and eventually move in. For some reason, this didn’t bother me but perhaps in a film that commits to a broader cinematic realism, I would’ve been lost right away.

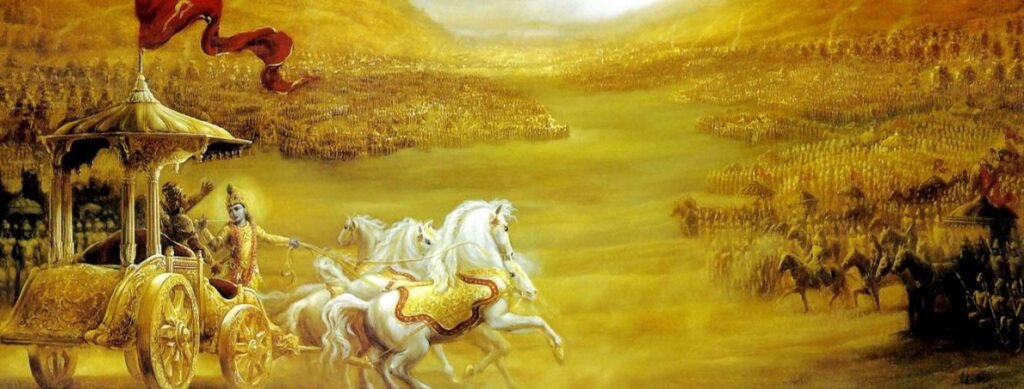

This elevated reality is what serves musicals very well, and I thought immediately of Hindi cinema a.k.a. Bollywood. In Hindi films, we are keenly aware of the theatricality because, of course, people don’t break out into song in real life, strictly speaking. So the melodrama inherent in Bollywood is forgiven because the cinematic language sets up this deviation from reality.

I was also reminded of another country’s master filmmaker, Spain’s Pedro Almodovar. At QFS we watched his All About My Mother (1999, QFS No. 109) and what struck me then is that the film felt like a telenovela with its plot twists and turns. Almodovar’s mastery of balancing melodrama and realism is one of a kind and is perhaps the only filmmaker I know who’s been able to pull off authentic emotion with twisting and turning plots that defy reality.

Somewhere in the spectrum between Bollywood and Almodovar lies Douglas Sirk. More than half a century ago, Sirk uses melodrama in Imitation of Life to probe the problematic racial dynamics in his adopted country, the United States. Originally from Germany, the filmmaker fled Nazi persecution and made a career in the American movie industry. I’ve noticed that often it takes a foreign-born director to keenly see some of the divisions of America and render them into art on the screen. In college, I had a terrific course that explored America through the lens of foreign-born directors. Though Sirk wasn’t in the course, he very well could have been where he would’ve joined the ranks of Milos Forman (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 1975, QFS No. 75), fellow German émigré Fritz Lang (Fury, 1936, QFS No. 37), and Wim Wenders (Paris, Texas, 1984), among others.

One of the commonalities those directors displayed was a foreigner’s ability to both admire their new homeland and also criticize it, warts and all. Which is also a way of expressing love of their adopted country. In Imitation of Life, Sirk sees that a white person can flourish, reach their heights, seemingly on their own. But in the background, working in the kitchen unseen, is their black counterpart toiling away. Lora ascends to the top of her career while Annie (Juanita Moore) supports her faithfully.

But at what cost? Annie is unable to convince her daughter Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner) – a girl who can pass as white – that being black is nothing to be ashamed of. Perhaps the love and care she spent supporting Lora and her daughter Susie (Sandra Dee) is the cost for Annie. While Sarah Jane’s struggles are deep, existential, and wrenching, Susie’s amount to feeling as if her mother wasn’t around to spend time with her. Not to trivialize Susie’s angst, but Sirk feels like he’s making a sly commentary here. A black girl’s struggle in America is very deep and profound while a rich white girl can have the luxury of not worrying about her personal identity but instead can worry about the usual things children worry about.

What struck me throughout the film is that the characters don’t live in a time where they have language to address or understand race relations. Lora doesn’t offer meaningful support other than to suggest that things will get better. And Annie is unable to talk to her daughter about race in a nuanced or meaningful way. Of course, they are living in a time where divisions are very real between white and black families – the decision that struck down legal segregation, Brown v. The Board of Education, only happened five years before Imitation of Life was released – so it’s understandable that they don’t know how to talk about race in a constructive way. We’re still struggling with it now, but we have more language and tools. What I’m saying is: everyone in this movie would’ve benefitted from being in therapy.

For me, the entire film is worth it for this one particular payoff: the scene where Annie in essence says goodbye to Sarah Jane. Annie has discovered that Sarah Jane has moved across the country to Hollywood with a new name, working in a chorus line as an object of desire (or as lascivious a job as could be permitted to portray in 1959). Annie goes to her and is done fighting with her daughter, but instead only wants to hold her. As a final act of motherly love, she does what Sarah Jane asks – to leave her alone and pretend they aren’t related.

The hold each other and both cry in each other’s arms. The roommate enters and as Annie leaves, she tells the roommate she used to raise “Miss Linda” – Sarah Jane’s new name, tacitly acknowledging her daughter is someone else now. After Sarah Jane closes the door, she cries sans says she was raised by a “mammie” “all my life.”

It’s devastating, and I did my best to keep from crying as much as they did. Throughout the film, Annie attempts to relentlessly be a mother. And in the end, what’s the most motherly thing she could do? Set her daughter free and assure her she could come back any time and her mother would be there to love her.

The melodrama builds and crescendos to this and somehow, even though the film doesn’t adhere to strict realism in anyway, I felt like I knew these people, these characters. As an American-raised child immigrants, I too have felt in many ways the way Sarah Jane felt in the film. I didn’t want to be seen as different than the other kids at school and at times not want my parents around where my classmates could see them. Sarah Jane is mortified when her mother comes to school to bring her an umbrella, revealing to the others that she’s actually black. I can’t say that I had experiences exactly like that, but I completely understood the character’s struggle in those scenes in a deep way.

Douglas Sirk gives the heft of the narrative to this story of identity, of race, in a way that’s uniquely American, and puts the burden on Juanita Moore in a titanic performance as Annie. In a meta way, Annie, the black character, has the bigger character arc, the bigger struggle, than Lora, played by one of Hollywood’s biggest stars Lana Turner. But it’s Turner that gets top billing, gets the posters and the recognition and, of course, the money. This too is a commentary, though unintended, about America, about life, and about Hollywood. In that way, Imitation of Life penetrates on more layers than maybe it even intended.

Halfway through the film, Annie deeply knows Sarah Jane’s struggle and says to Lora, “How do you tell a child that she was born to be hurt?” To utter this in a mainstream film in 1959 is no small feat. The fact that it’s probably still relevant is the real tragedy of Imitation of Life. Yet another aspect of what a modern 21st Century film this 1959 melodrama truly is.

Godzilla Minus One (2023)

QFS No. 151 - This is the first kaiju film selected by Quarantine Film Society. Kaiju, of course, is the film subgenre in which giant monsters destroy things. I think it’s amazing that what seems like a very limited type of film has a named subgenre, but this is where I’m wrong. There are tons of these movies and television shows varying in quality in the 70 years since Godzilla (1954) came out from Japan. I’m certainly no expert on these films, but I do enjoy a good giant animal picture now and again.

QFS No. 151 - The invitation for September 4, 2024

Godzilla Minus One (2023) is the first kaiju film selected by Quarantine Film Society. Kaiju, of course, is the film subgenre in which giant monsters destroy things. I think it’s amazing that what seems like a very limited type of film has a named subgenre, but this is where I’m wrong. There are tons of these movies and television shows varying in quality in the 70 years since Godzilla (1954) came out from Japan. I’m certainly no expert on these films, but I do enjoy a good giant animal picture now and again.

Godzilla Minus One created quite a buzz last year and I really wanted to see it. I’ve heard good things about it from a filmmaking and storytelling perspective, but also in the visual and special effects. If I’m not mistaken, they had a very slim VFX team compared to say big studio movies. And yet, they took home the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, beating out a Marvel film, a Mission: Impossible film and Ridley Scott who is no stranger to Visual Effects. The first foreign language film to win the Visual Effects Oscar, which is cool.

Speaking of, this will be our fifth selection from Japan but our first Japanese film from this century. So curl with Godzilla Minus One and watch a giant lizard break things! (#spoiler) Join us next week for Godzilla Minus One.

Reactions and Analyses:

Is Godzilla’s destruction purposeful? Does he (it, she, they) know what he’s destroying? Is it intentional? Or is the destruction indiscriminate?

That was one of my main questions for the QFS discussion group and several were curious about this as well. And perhaps, for a mega-superfan of kaiju films, this is a question that’s very basic. But for someone like myself, it seemed an important question.

Perhaps the reason why I’m curious about this is that I’m not sure how to feel towards Godzilla. In some sense, if the destruction is unintentional, there’s a bit of sympathy one can feel towards the creature. It doesn’t know what it’s doing, it’s primal and a production of human tampering with nature – then it’s almost justified in its actions. A force of nature. After all, you can’t be angry with the actions of a hurricane or a volcano because it’s something unlocked by the Earth.

But if Godzilla is an avenging god, wreaking havoc on a populace already suffering from the toll of devastating global war – then, it gets a little complicated. Godzilla, portrayed for seventy years on the big and small screens, appears in Godzilla Minus One as being fueled - or at least “embiggened” - by human’s insatiable need for bigger, larger and more destructive weapons. A scene, almost a cutaway scene, depicts the US dropping experimental nuclear bombs on the Bikini Atoll – with an insert shot of an underwater monstrous eye opening and powering up. The implication is this is what humans hath wrought. Nuclear war and self-annihilation.

Or as metaphor, a giant uncontrollable lizard getting larger and larger as it destroys more and more. A stand-in for the arms race writ large.

All Godzilla films are metaphoric and perhaps cautionary, from the original 1954 version to this one in 2023, borne of post-war Japan where nuclear annihilation was not theoretical but actual. It’s astonishing to realize that only nine short years after World War II and on the heels of the nuclear bombs wiping out Nagasaki and Hiroshima, that Toho Studios would make a film about a creature that was destroying Japanese cities. I even had this feeling while watching the 2023 iteration, that these poor people had suffered enough from fire bombings and nuclear weapons – isn’t it a bit too much to also subject them to a giant destructive lizard?

Perhaps this is where cultural tastes and takes diverge between the US and Japan, which came up in our conversation. It’s easy to imagine that if the roles were reversed, that US filmmakers would very much make a film of giant monsters attacking Japan or Germany – their enemies in that war – as opposed to attaching its own populace on the shores of the Untied States . We found ourselves pondering what would’ve happened if Japanese filmmakers did indeed decide to make a 1954 film of Godzilla attacking the US, a revenge fantasy film in the way that would make the likes of a young Quentin Tarantino proud. Retribution through art is something we’ve seen before, but the Japanese have resisted that and instead turn inward with the Godzilla films.

And especially in Godzilla Minus One. Shikishima (Ryunosuke Kamiki) was a naval flyer in the war but when we discover him, he’s abandoned his duty as a kamikaze pilot honor bound to die in a suicide attack against the Allies. Although this is shameful, culturally, in 2024 looking back the filmmakers turn this around and seem to say – yes, that was your duty then, but now we need to live and build our nation. And by ejecting just before he flies into Godzilla’s mouth with his bomb-laden plane, Shikishima saves the day, lives honorably, and lives on – even rewarded by discovering that Noriko (Minami Hamabe) is still alive. So living is worth living for, you see.

The nationalistic pride in Godzilla Minus One evoked another recent film we’ve screened from another part of Asia - RRR (2022, QFS No. 86). In S.S. Rajamouli’s revisionist period piece, India is a place that had physical might and used violence and warfare to overthrow British rulers. Never mind the fact that this never happened and India is well known for its nonviolent moral and intellectual revolution that truly changed the world (as portrayed in Gandhi, 1982, QFS No. 100) – the India of 2022 is trying to assert a new world dominance. One that shows its military, technological and physical might as opposed to its intellectual and moral one from the past. RRR is a virulently nationalistic work of fiction that seeks to scrub that past and recast India as a mighty nation, ready to do battle. I, for one, found this appalling and will discuss further in the RRR QFS essay that remains TBW.

And yet, there’s a parallel we found in our discussion with Godzilla Minus One. Japan was demilitarized after World War II and there was a sentiment that they might prefer to live that way, to build their society and give up their imperialistic past. In 2024, the world is a vastly different place. With a resurgent and belligerent China at their doorstep, is Godzilla Minus One recasting Japan’s past, to show that they have might in numbers and a national pride? And that this means their love of the Japanese country fuels their current military force for good and will keep the Chinese at bay? The former soldiers in Godzilla Minus One fight not because it’s their duty as soldiers, but it is their collective duty to build a nation of people, assembling a “civilian” navy to fight an enemy at their shores. One can interpret that this is all proxy for regional domination and moral superiority over a foe, even if it’s not overt. (Though, to me and others in the group who brought this up, it feels overt.)

But while the film does have this national pride coursing through, there is ample criticism of the Japanese government. The former admiral Kenji Noda (Hidetaka Yoshioka) says:

Come to think of it this country has treated life far too cheaply. Poorly armored tanks. Poor supply chains resulting in half of all deaths from starvation and disease. Fighter planes built without ejection seats and finally, kamikaze and suicide attacks. That's why this time I'd take pride in a citizen led effort that sacrifices no lives at all! This next battle is not one waged to the death, but a battle to live for the future.

There you see this pride, but also damnation of nation’s leadership. It’s a fine line for the filmmakers to walk and they do so pretty well. Which got us to thinking – this is about as good as you can make this type of film, isn’t? The filmmakers balance politics, human drama, and action in a film about a giant lizard destroying everything in its path. There’s ample metaphor, there are emotional stakes – it all comes together in an science fiction film.

I does feel, however, of the scant Japanese Godzilla films I’ve seen, this one has taken some of the worst of American action film schlock and absorbed it, much the way Godzilla absorbs ammunition rounds. There’s the extremely cheesy lines, the overwrought emotions and overly convenient storytelling. Unfortunately, Noriko is saddled with several of these – Is your war finally over? As her first line to Shikishima when they reunite at the end feels straight out of the worst Jerry Bruckheimer/Michael Bay collaboration. Is that … Godzilla? Is one of the more useless expressions of dialogue you’ll find in a movie but it did make me laugh out loud (unintended comedy laughter is still laughter I guess). And of course, Noriko somehow survives Godzilla’s energy breath blast giving us the happy American-style (or Bollywood-style) ending we’ve come to expect with a massive film like this. Not to mention the somewhat predictable climax, where Shikishima ejects and survives as well.

Are these flaws or features? Any way you slice it, to make a film about an indiscriminate killing force that destroys on a large scale, is no small feat (pun intend… small feet… never mind). But to make it memorable, you have to make it about people, not about the lizard. And even if their emotions are not totally believable, they sure are more believable than a giant monster reigning terror across a nation. The bringing together of both make for what might just be the apex in kaiju – specifically Godzilla – movie making.

L.A. Confidential (1997)

QFS No. 150 - In 1931 and 1932, there were a few gangster pictures that helped established the genre – Little Cesar* (1931), The Public Enemy (1931) and this week’s selection Scarface (1932).

QFS No. 150 - The invitation for August 28, 2024

I’m fairly certain that everyone or nearly everyone reading this has seen L.A. Confidential, one of the great Los Angeles movies and truly a modern classic in so many ways. You’ve got a young Russell Crowe, not yet a household name, the steely-eyed Guy Pearce, Kim Basinger with probably her best performance, director Curtis Hanson’s exacting detail of the period and his fantastic adaptation of James Ellory’s period novel. And, well, okay, it does have Kevin Spacey but we don’t have to talk about that right now.

Aside from him, I’m partial to the overall excellence in the cast, which was put together by casting director Mali Finn. Mali cast L.A. Confidential and Titanic (1997), both of which came out the same year. Three years later, I moved to Los Angeles and was hired by Mali to be her assistant – my first job in the industry. To my additional great fortune, in the spring of 2001 we started work casting Curtis Hanson’s follow-up to L.A. Confidential, the Eminem-starred 8 Mile (2002). A cinephile who was closely involved with the UCLA Film & Television Archives, Curtis told us early on that he was approaching 8 Mile as a modern Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and hosted a screening of Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1978) for insight into the tone. What I’m saying is that Curtis would’ve enjoyed being a part of QFS or at least the idea of it.

Curtis, James Cameron, Joel Schumacher, Sharat Raju* and dozens of other directors loved having Mali as their casting director and she was known as a director’s casting director. She cast “real” seeming people and didn’t fall for beautiful faces, something I came to appreciate in my time working in her office alongside her. If you look at the films she worked on – and there were a lot of them – you would likely see a commonality in the actors who make up the fringes of the supporting cast. The ensemble for lack of a better term. I would argue (I mean, I have argued this point) that Titanic’s supporting cast are just as compelling as the main stars and possibly more so. That’s Mali’s fingerprints on Titanic, and you’ll be able to see that care in populating a cinematic world in this week’s selection as well.

L.A. Confidential is also part of what is truly an incredible film year, 1997. Check it out – joining this week’s film and Titanic, at the Academy Awards alone you’ve got As Good as it Gets, Good Will Hunting, Life is Beautiful and The Fully Monty hitting the big categories. Then throw in Boogie Nights, Contact, Princess Mononoke, the first Austin Powers, Jackie Brown, Men in Black, Liar Liar, Wag the Dog, The Fifth Element, Tomorrow Never Dies (the best of the Piece Brosnan Bond films?), Con Air, The Game (underrated Fincher film), Face/Off, Gattaca, I Know What You Did Last Summer, Donnie Brasco, Gross Pointe Blanke, My Best Friend’s Wedding (solid Julia Roberts romantic comedy), Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm – I mean good lord we could have a screening series just on 1997!

I remember watching L.A. Confidential in the theater before I had ever even visited Los Angeles, and loved it. I’ve rewatched the film numerous times since moving to and living in LA and there’s an additional level of enjoyment you get from seeing sites that still exist – which can be an oddity in LA – as well as areas that feel very much a part of the city's past. Curtis Hanson, a native Angeleno who was probably a child when the events of this film take place, is meticulous in his recreation of that time. The DVD (which I still proudly have on my shelf) has terrific featurettes that are basically Curtis giving a tour of shooting locations in LA and they’re bite-sized and lovely.

Our 150th selection just felt like an appropriate time to revisit this film and its cool, stylish take on 1950s Los Angeles that has the slightest of connections to yours truly. I’m looking forward to revisiting it with you all and raising a glass for crossing a new QFS milestone.

*Shameless, I know.

Reactions and Analyses:

Closer to the end of L.A. Confidential (1997), Captain Dudley Smith (James Cromwell) holds a conference with his Los Angeles Police Department officers announcing the details of the death of one of their own, Detective Jack Vincennes (Kevin Spacey) and instructs everyone to find the killer at all costs. This is all misleading, of course, since it’s Dudley himself who killed Vincennes. But only we, the audience, know that.

As the officers are filing out, he summons Detective Ed Exley (Guy Pearce) and mentions that Vincennes had a lead, and maybe it was in regards to his killer. The name, uttered in Vincennes final breath to Dudley, was “Rollo Tomasi.” The name is a fictional moniker Exley gave to the name of the man who killed his father and was never found – and only Vincennes knows about it.

It’s here that Exley now knows the truth – Dudley killed Vincennes. It’s the final piece of the puzzle that solves the Night Owl killings and answers a host of other questions for which Exley had been searching.

The shot has remained on the back of Exley’s head throughout this exchange. But once this name is mentioned, it cuts to his close up. And lingers on it – long enough for the audience to know, but we also want to know what is Exley going to do or say? It’s suspenseful, it’s tense and it’s simply a cut to a close up. Exley has to register it, decide, not betray any emotion, and come to a realization – all in a simple close up.

The next shot, it’s back to the back of his head, Dudley leaves, and Exley turns to camera, a close up again – and he’s shaken and something has changed.

It's an extraordinary moment in an extraordinary work of directing. It’s a bringing together of performance, cinematography, writing, and directing. It encapsulates what a great director does – bring together all the elements that make up a movie and synthesize them into something greater than their parts. Curtis Hanson does this masterfully throughout L.A. Confidential and re-watching the film for the seven hundredth time (give or take) gave us the opportunity to revel in the true excellence of his craft.

Perhaps it’s easy to forget that Guy Pearce and Russell Crowe (as Bud White) were total newcomers to American audiences in 1997. And take Crowe’s Bud White in Hanson’s hands as both director and writer. When I first saw the film in the theater 27 years ago, I remember loathing Bud White but also fearing him, which I think is the point. But this time, I picked up on something that might seem obvious but was new to me.

All the characters in the film are hiding something or angling for something. Dudley clearly is hiding his corruption. Exley is a climber – on the surface he’s a good cop, and truly he is. But he’s playing the angles, understanding how to get higher in the ranks. Lynn Bracken (Kim Basinger) is literally appearing to be Veronica Lake but is actually a girl from Bisbee, Arizona – and cheats on White with Exley to get Exley in trouble or killed. Pierce Patchett (David Strathairn) appears to be a businessman but he’s caught up in prostitution and drugs. The D.A. (Ron Rifkin) is a closeted homosexual. Vincennes appears slick but loathes what he does. And so on.

But the only one who is “pure,” who we can say is what you see is what you get – that’s Bud White. In a way, he’s the least corruptible. That’s not saying he’s a clean cop. On the contrary, he’s part of Dudley’s squad that beats up rival gangsters off the records. But he’s true to himself, the boy who watched his father beat his mother to death and has the physical and mental scars to prove it.

If there’s a thesis in L.A. Confidential it’s this – to have people protect us from the evils in the world, you can’t do it with just brawn and you can’t do it with just brains. You need both. So while Bud White is the brawn, he uses his brain to connect the dots and discover that his former partner Dick Stensland (Graham Beckel) lied to him and was part of a heroin racket.

And Exley, in what is probably the best glasses-wearing police officer portrayal in history, goes from what we believe is bookish, shrewd, and prestige-chasing to someone willing to plant evidence and shoot someone a fleeing suspect in the back. The very things he tells his superior, Dudley, he’s not going to do because that’s not the right way. And it’s Dudley who he shoots from behind after all is said and done.

This convergence of brain (Exley) and brawn (White), and how each transform into the other, culminates in the scene where the two nearly kill each other. Exley barges into Lynn’s home and they then have sex – but it’s all a setup with Sid Hutchins (Danny DeVito) taking blackmail photos “accidentally” given to White by Dudley so White then is driven to kill Exley. And he very nearly does until Exley reveals that he knows Dudley killed Vincennes. White, still enraged, ultimately burns off and does not go through with destroying Exley.

It's this turn, this moment where brawn gives way to brains, this moment that saves both of them and sets them on a path to ending Dudley’s secret reign of terror. Brain without brawn is feckless and powerless. Brawn without brains is primitive and intractable. Both are needed to balance each other, a yin and yang.

L.A. Confidential succeeds in being rooted in reality, and while it starts with the cast – every single one of them is a full three-dimensional human, fleshed out and realistic – the world created by Hanson makes the film feel as if it was something that actually happened in Los Angeles in 1953. Of course, though some storylines are based on a handful of real stories in James Ellory’s original novel, Hanson’s visually recreates 1950s Los Angeles with exacting detail. But he doesn’t do it for show or make a big deal of it – it’s all in the background. The pushing back of the details gives the film a verisimilitude that brings it to life.

There’s one example in particular that is detailed in a terrific museum piece at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles. Production designer Jeannine Oppewall and set decorator Jay Hart talk about Lynn Brackett’s home – it’s filled with flowing, silky, “lounge-y” fabrics in a home with archways and layers. But in the back of the home sits Lynn’s bedroom, hidden away and small. It’s simple and the camera pans over to a little pillow that’s clearly homemade of Arizona, with the town of Bisbee highlighted.

That’s the real Lynn Bracken – a girl from Bisbee with layers of glamour on the surface, hiding the true person inside. It’s a symbol of the film, the story, and frankly of Los Angeles. And it provides an example of the attention to details that are in the background and though you might not notice them, they do their work on you, the viewer, to root it in a reality. And with that in the background, the performers have a chance to in the foreground of the film.

This is also another example of what it means to be a director, to pull in those elements and create a world what is this richly layered and detailed.

One of those elements that routinely shines is Dante Spinotti’s immaculate cinematography. In particular, how he and Hanson use close ups in the film. As described above, closeups are used as punctuation – of Ed Exley realizing that Dudley is Vincennes’ killer. But one close up in particular stands out and it’s the moment that White discovers Lynn at the liquor store. At first he can’t see her face – she’s in a black clock with white trim. But then, she turns to him – to us, the camera – into a stunning close up, Kim Basinger/Veronica Lake/Lynn Bracken in all her glamorous beauty.

It’s evocative of the glamour headshots of the era, of the stunning shallow focus, frame-filling shots of the time. And it’s a powerful character introduction. This is a person of consequence to the story. Throughout the film, Spinotti and Hanson push the limits of the close up, cutting off top of heads in the 2.35 aspect ratio, to bring us very close to the subject. For a film with so many main characters, it’s never confusing whose perspective we’re in at any given time. We always know whose eyes we’re seeing a scene through. Whether it’s looking up to see a Santa Claus decoration on a roof that’s about to come down or looking at two suspects in an interrogation room, we always know whose story we’re following and when – that’s the work of a director, a cinematographer, and an editor telling the story visually.

L.A. Confidential is one of those rare films in which every single person involved in it is at the top of their game. Everyone is hitting home runs. It’s a powerhouse of collaboration which means it’s a powerhouse of directing. A textbook film to watch if you’re interested in production design, period costumes and props, locations, history, cinematography, editing, music, performance, writing – therefore a textbook of filmmaking. Let’s hope we’re still studying now and for years to come.

Scarface (1932)

QFS No. 149 - In 1931 and 1932, there were a few gangster pictures that helped established the genre – Little Cesar* (1931), The Public Enemy (1931) and this week’s selection Scarface (1932).

QFS No. 149 - The invitation for August 21, 2024

In 1931 and 1932, there were a few gangster pictures that helped established the genre – Little Cesar* (1931), The Public Enemy (1931) and this week’s selection Scarface. Any of those would’ve been fun to watch, especially with stars like Edward G Robinson and James Cagney (who you may remember as being wonderfully bonkers in White Heat, 1949, QFS No. 74). So perhaps we’ll visit one of these other Pre-Code gangster films in the future.

“Pre-Code” of course refers to a film that predates the Production Code Administration censorship era that befell Hollywood starting in 1934. In 1932, the year Scarface was released, the film industry’s distribution oversight commission – called the Hays Code – had no real authority to mandate the removal of controversial elements from a film. Their notes were suggestions which were adhered to or not adhered to depending on the filmmaker’s or the studio executive’s muscle. This self-policing model gave rise to conservative vanguards of moral decency who threatened widespread boycotts of films with content they deemed immoral. The PCA was established and its stamp of approval began in 1934 and aimed to quell the discontent from these voices. That system continued for the next 36 years, finally replaced by a rating system that’s a precursor to our letter-based one we use today.

So there was a window of time from about 1922-1934 where many films pushed the boundaries of content, tone, style, and story. Scarface fell in that realm and faced real opposition with heavy censorship efforts from the studio. The PCA code intended to make sure that films didn’t glorify gangsters and other evil-doers, and instead they should receive comeuppance. Crime doesn’t pay, is the acceptable moral takeaway. To be somewhat fair to these censors, the 1930s was still rife with mafia-driven crime in major cities. Al Capone – upon whom Scarface is apparently based – was still very much alive and influential in Chicago in the ’30s.

Speaking of Capone – though loosely based on a novel, the Scarface script is co-credited to the legendary Ben Hecht who is almost certainly the most prolific writer in movie history (though he was one of five writers on this script – five!). Hecht apparently had once met Capone and based the main character on him, so much so that Capone had two men “visit” Hecht in Hollywood to make sure it wasn’t … too much based on Capone. (We’ve watched a Hecht penned film before, Alfred Hitchcock’s masterpiece Notorious (1946, QFS No. 117)

All of this is compelling enough to want to see Scarface, and that’s before mentioning that it was produced by the most famous wealthy future recluse of all time, Howard Hughes. With Hawks at the helm, you’ve got a double Howard film. The Full Howard, as it’s known by no one.

Watch the 1932 Scarface (not the 1983 one!) and let’s discuss!

*Not to be confused with the pizza, though both are made out of celluloid (ZING!).

Reactions and Analyses:

“The World Is Yours.” This is the advertisement Tony Camonte (Paul Muni) – the titular “Scarface” – sees when he looks out the window of his gaudy new apartment, financed from moving up in the ranks as the strongman to Johnny Lovo (Osgood Perkins). There it is, a literal big, bright, shining sign, illuminating his vision forward.

If there’s a thesis statement for Scarface (1932, and by extension the 1983 version), it would be that exact statement. The ambition of a man low on the totem pole, seeking more power, more money, more women, more of whatever it is he desires. You can take it – after all, it’s yours. “Do it first, do it fast, and keep doing it,” Tony says early on in the film.

And throughout, Tony appears to be angling, smiling, grifting, posturing. His charm and charisma are obvious and as officially the muscle of Lovo’s operation, it’s clear that this is a problematic staff hire Lovo has made. Tony’s proving that he’s not really someone who follows orders and we see the two different dynamics of gangsters – a dynamic that plays out in gangster films for decades to come. The shrewd, calculating and often cautious puppet-master/chess player on the one hand and the violent, unpredictable, hot-headed reactionary who’s not afraid to dive headlong into battle. This is the Michael Corleone/Sonny Corleone dichotomy that’s at center of The Godfather more than 40 years later, for example.

Scarface, along with the other Pre-Code gangster classics Public Enemy (1931) and Little Cesar (1931), all released within a few years of each other, form an origin triumvirate of the gangster genre that continues all the way through today. Throughout the film there are familiar faces, ideas and themes – but in 1930s, they were likely novel. You’ve got the second-in-command Rinaldo (George Raft) with his coin-flip as a signature tic, the woman who is attracted to criminals and bad boys, the clownish sidekick Angelo (Vince Barnett), the attempt to go out in a blaze of glory, the relentless gunfire, the psychopathic and heartless killer, and so on. It’s actually sort of thrilling to watch this genre in its infancy.

About the psychopathic and heartless killers, Hawks and screenwriter Ben Hecht likely had portray antihero Tony as someone who would inevitably have no chance of ending up on top. This is a contrast of course to Michael in The Godfather who does succeed by vanquishing his foes, killing his sister’s traitorous husband, consolidating his power and earning the respect of his underlings. The Pre-Code censors in 1932, however, would not permit a positive portrayal of a ruthless gangster. He has to have his comeuppance, and Hawks concedes to the censors and places a plea for help in the opening title card:

This picture is an indictment of gang rule in America and of the callous indifference of the government to this constantly increasing menace to our safety and our liberty. Every incident in this picture is the reproduction of an actual occurrence, and the purpose of this picture is to demand of the government: 'What are you going to do about it?' The government is your government. What are YOU going to do about it?

There’s also this aspect of Tony that he isn’t just cruel, but that he must also have a psychosis in the way that James Cagney has in White Heat (1949, QFS No. 74). At the time, Hawks likely couldn’t portray Tony as simply an ambitious Shakespearean tragic figure, about one man’s pursuit of power because that would in a way be an indictment about the American dream. Fifty years later, Brian DePalma and Oliver Stone have nothing in their way to prevent them from reimagining this tale as a saga of an immigrant coming up from nothing and earning his place in a twisted version of the American dream. The World Is Yours, after all. Both go down in a blaze of glory, but Tony Montana in 1983 goes down, guns blazing, crashing into a pool. Tony Camonte in 1932 goes down sniveling, afraid of being alone and distraught at what will happen to him. A “hero’s” end in 1983 but a coward’s end in 1932. This is perhaps the biggest distinction between the films and between the eras. We sort of admire Tony Montana, ruthless as he is; it’s hard to say that same about Tony Comonte.

In 1932, Tony Comante dies sniveling and begging.

In 1983, Tony Montana (Al Pacino) goes out in a more "heroic" or honorable blaze of glory in Brian De Palma's Scarface.

In the 1932’s Scarface, Tony gets his hands on a new weapon of mass destruction – the Tommy Gun, ubiquitous in gangster films from here on out. And he’s filled with murderous glee, looking to turn the North Side into Swiss cheese. He lashes out furiously at his sister Cesca (Karen Morley) for dancing with men at a club and strikes her. Later, he kills his best friend Rinaldo in a rage later on when he finds Rinaldo and Cesca together not knowing that they secretly were married while Tony was away. Perhaps a way to show that this is not a man to admire is to show that all of this behavior is aberrant. In a way, it ends up being an anti-gangster film. A member of our group pointed out that for about two-thirds of the way into most gangster films, the lifestyle seems pretty great. It’s the downfall that’s brutal.

Look how similar these two images are! And the joy in Tony Comante's face.

Both the 1932 and 1983 version feature weapons capable of doing maximum harm and serve no appropriate civilian purpose - more explicitly addressed in Howard Hawks' film than in De Palma's. And here, in this photo, Tony Montana (Al Pacino) has a little friend. You must say hello to it.

Members in the discussion group pointed out one particularly unfortunate and dispiriting aspect of Scarface, but not in a story sense. Mid-way through the film, a publisher and a politician who appear in essentially only this one scene, lament that these automatic weapons gangsters are now using have no purpose except for mass murder – and that they’re powerless against them unless the government does something about it. We’re still having this problem now, in 2024! It was actually a very depressing scene – and overtly racist unfortunately, arguing that half of these Italians aren’t even American citizens and thus should be rounded up and deported. We’re still having people argue this now, in 2024! The scene goes on to have one of the characters enumerate other ills of society in a list that almost exactly mirrors the text in the Hays Code of 1932 and the Production Code in 1934 – a scene clearly meant to appease the censors. The scene also features the publisher of the Chicago paper defending their work, saying that they have to report on the news while the government takes the position that the newspapers are simply glorifies gangsters and violence. We’re still having this discussion now, in 2024!

Gun control debates, racist tirades and media complicity aside, Scarface is surprisingly advanced for 1932 and artistic in the seasoned hands of Hawks. The car stunts are exciting and clearly dangerous. The gunfire is realistic because, well, we learned they had to use real bullets firing around the actors to create bullet hits since this film predates the use of squibs. Nearly every single picture window gets utterly demolished, which leads one to question why any gangster would openly sit near a window at all during a drug war. They are liberally spraying bullets all over the place in the film and it’s quite thrilling, I have say. Hawks is an underrated artist in the grand arc of American cinema history, but this film showcases his artistry as a director – the use of the letter “X” somewhere in the frame whenever someone is about to die might be the first ever Easter Egg in a movie? But his use of action is very effective and it’s clear that he’s mastered the use of early special effects to simulate cinematic reality – all only a handful of years after the end of the Silent Era, which is amazing.

In so many ways, gangster films have come a long way. But in a lot of aspects, the fundamentals of the genre can be traced to this film and others from this time before American censors really crack down on portrayals of criminals as heroes. One commonality is the idea that if you are ruthlessly committed to the pursuit of power, then glory awaits. The world, after all, is yours.

Blow Out (1981)

QFS No. 148 - Brian Da Palma is one of the great polarizing filmmakers of our time, I think I can safely say. He has made some of classic films – Carrie (1976), Obsession (1976), Scarface (1983), The Untouchables (1987), the first Mission: Impossible (1996) – but has also made several bombs. Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) was a legendary box-office disaster and Mission to Mars (2000) is a truly terrible film and I dare you to convince me otherwise. But it’s not the financial failures of some of this films that have made him polarizing.

QFS No. 148 - The invitation for August 14, 2024

Brian Da Palma is one of the great polarizing filmmakers of our time, I think I can safely say. He has made some of classic films – Carrie (1976), Obsession (1976), Scarface (1983), The Untouchables (1987), the first Mission: Impossible (1996) – but has also made several bombs. Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) was a legendary box-office disaster and Mission to Mars (2000) is a truly terrible film and I dare you to convince me otherwise. But it’s not the financial failures that have made him polarizing.

His thrillers are dark psychological affairs with often erotic storylines, disturbing imagery, and bloody violence. Dressed to Kill (1980) ignited protests over the portrayal of a transgendered person as a deviant psychopathic murderer. Body Double (1984) upset his studio so much that they ended his multi-picture deal. Scarface (1983) was criticized for its brutal violence and glorification of drug use. His admirers are legion, but his critics point to misogynistic tendencies in his films, in particular his thrillers. (Speaking of misogyny, he's been accused – or praised, depending on your perspective – of ripping off Alfred Hitchcock a little too liberally.)

But De Palma never made the same film twice and his filmography is impossible to characterize or really fathom. His work includes: a Stephen King-horror film, a violent immigrant gangster opus, a slick Chicago-set period piece with an homage to a Russian silent film, the launching of a major movie franchise, a war film, science fiction, musical, comedy, thrillers. It’s really astonishing the breadth of films De Palma made, especially for an auteur. The sheer fact that the studio system rewarded De Palma in the 1980s is fascinating, and a sign of the times perhaps. It’s harder to imagine a De Palma-type succeeding now.

Still, you could make the argument that Quentin Tarantino – who is De Palma Fan #1 – did do just that in the 1990s. Tarantino and De Palma are two filmmakers who have a committed and deep following, in almost a cult-like manner. It’s safe to say that many of his films are indeed being rediscovered as cult classics these days.

This week’s Blow Out is a film that has endured, at least for many cinephiles. Perhaps in part for John Travolta, as he was near the apex of the first half of his career and this is another early star turn for him. Whatever the case may be, this has been on my list of films to see for some time now, so I’m looking forward to finally adding a De Palma film to the QFS List.

Reactions and Analyses:

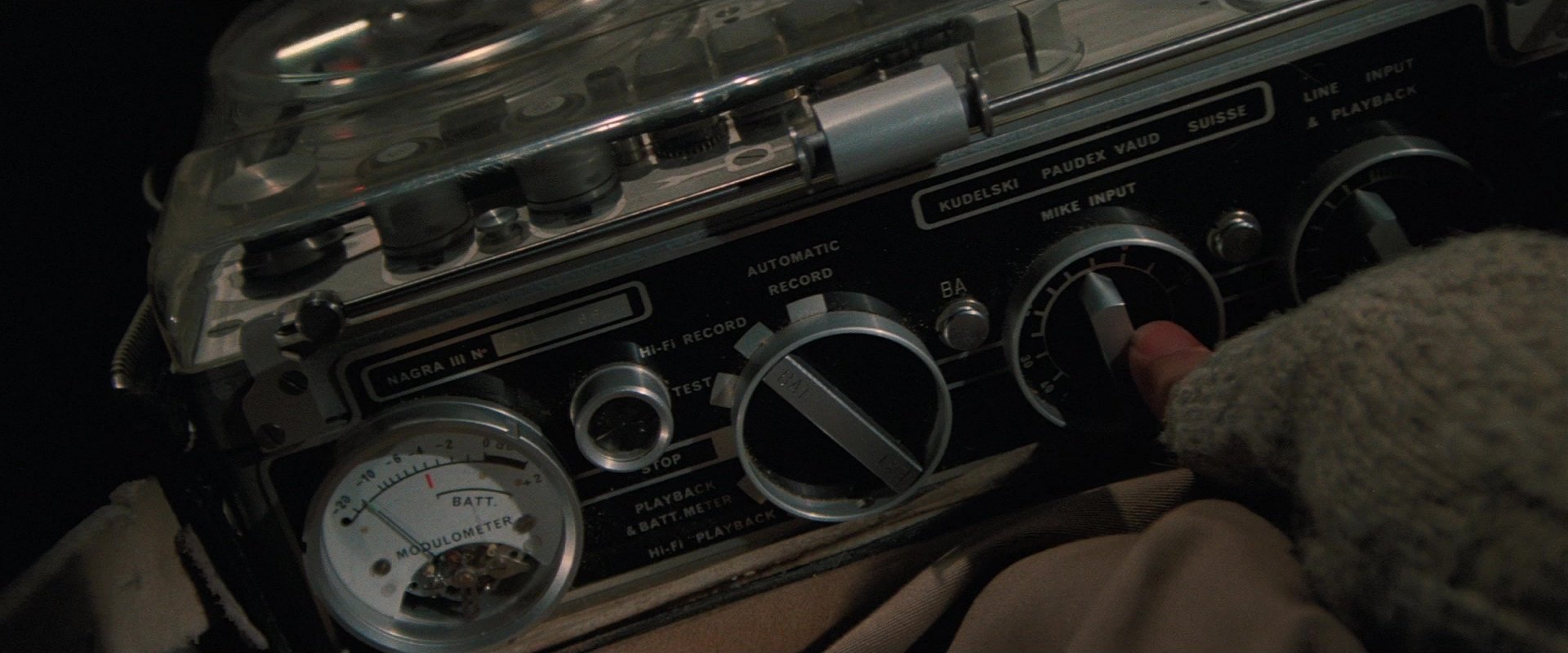

Early in Blow Out (1981), Jack (John Travolta) is on a bridge recording sounds as part of his work as a sound engineer for a movie production company. It’s a scene that becomes the inciting incident of the film, but at first it simply shows the character’s particular skill and expertise as Jack scans with his shotgun microphone through the night over the river. The scene also serves to show Brian De Palma at his best, putting his directing genius on display. If there’s one sequence I’d show someone from this (or any) film on what it means to tell a story visually, this might be it.

We first hear a couple talking near a bridge, in a wide shot while Jack is in the distance who’s listening in. The sound then trails to something mysterious, only to be revealed as a frog croaking. We hear some sort of clicking but don’t yet know what it is, but it leads to the owl hooting. The owl turns its attention, as we the viewer does and Jack does, to the sound of an approaching car. A pop – was it a gunshot or just a blow out?! – and the car spins out of control and goes over the bridge, which sparks the entire narrative journey of the film.

What De Palma does, and what Alfred Hitchcock also did so well, was to bring out attention to whatever the director wanted us to see. He puts the owl in close up, with Jack small in the frame behind him. We see the frog in foreground, but small and little, almost invisible the way it was to Jack but for hearing it. When we need to pay attention to something, De Palma puts it front and center.

Then, when the “accident” happens, we’re far away and don’t have all the details – which is exactly how Jack is experiencing it. This is textbook filmmaking, a sequence that should be mandatory for directors to show how to accurately direct the audience’s attention and to show first-person perspective in filmmaking.

De Palma, however, tops this by returning to the sequence and scene of the accident when Jack finally has a moment in a motel room with Sally (Nancy Allen) passed out on the bed after returning from the hospital. Jack listens to his recording and we return to the scene, hearing it and seeing it through Jack’s eyes. But now, we’re in different points of view, a fleshing out of the scene. The couple on the bridge is now seen from Jack’s perspective. The frog is clearly visible, now from a new angle. The owl, in close up, looks right at us and turns to the car approaching – but a new angle.

Then, the terrific shot of a flash in the bushes, the tire exploding – all with Jack and his headphones superimposed on the action, as if we’re in his head seeing and hearing it happen. It’s extraordinary – the stakes of this scene are high, this is what is setting up the central tension of the film. Jack has proof it wasn’t an accident, but an assassination attempt. Will anyone believe him?

Throughout Blow Out, De Palma’s work with cinematographer Vilmos Zigmond brings an elevated artistry to a suspense thriller, much as Hitchcock did a generation earlier. De Palma and Zigmond seem to know always where to put the camera to tell the story in the most compelling way possible. Take the opening sequence. In what feels like it could very well be the actual opening sequence of the film – a tawdry Halloween-esque opening that explores into a sorority house – is actually the film-within-the-film that Jack is working on. The scene goes on past what we expect for such a misdirect and it goes on for quite some time, finally revealed after a woman is about to be stabbed in the shower where her scream defies credulity and the images freezes. We’re now in the sound mixing room with Jack and his co-workers.

The sequence is itself a work of technical mastery – as much De Palma’s and Zigmond’s fine construction as it is Garrett Brown, inventor of the Steadicam, who executes the vision with his new device with perfection. Without having seen Blow Out before, I truly thought this was the beginning of the story. And what is serves to do (other than perhaps a comment on De Palma’s overt misogynistic tendencies, which we’ll get to) is to introduce us to Jack, his area of expertise, and also that he’s living in a sort of trashy B-movie world. The scream is a bit that will be returned to again and pays off at the end.

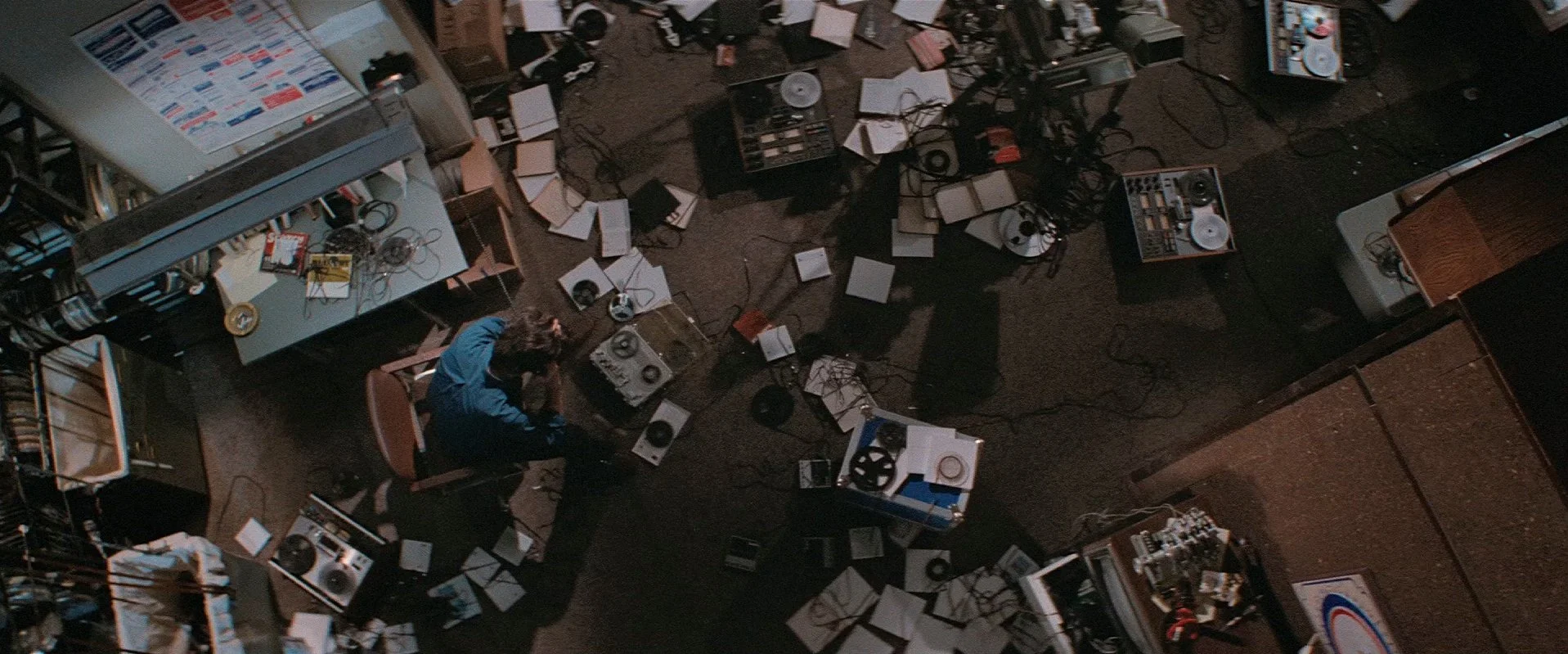

But before Blow Out ends, we’re treated to De Palma’s masterful attention to detail. For three quarters of the movie, roughly, De Palma’s attention to extreme detail is exacting, the way it is for Jack. We see close ups of the photos of the crash, frame by frame, as an editor would have to do. We watch all the practical and technical manipulation of the esoteric machines that shoot animation cells or string audio tape through a splicer, with chalk marks on the frames for reference. It’s tactile, the way filmmaking was, with physical levers and tapes that can be demagnetized. For a filmmaker who is part of what is likely the last generation to be trained in both analog and digital formats, all of this warmed my heart to see and that of several of us in the QFS discussion group.

Speaking of old-time filmmaking – Travolta portrays a sound engineer with utmost accuracy. Having known and worked with several, I can say that Travolta doesn’t feel like an actor playing a sound engineer, he somehow brings an authenticity to the role with his clear love of careful listening and focus. He fits perfectly into the role of Jack and I would’ve bought all the Travolta stock I could after this film – which is only funny in retrospect considering the following nosedive his career suffered until his resurgence in 1994 with Pulp Fiction (directed by De Palma Fan #1 Quentin Tarantino). But here in Blow Out, Jack is compelled to do something, anything he can, with the knowledge he has. He can’t believe how no one belives him and encounters forces out there, unseen, that are dangerous and are trying to manipulate our world.

This post-Watergate paranoia remains a fascination of mine. It was in the air - something or someone is manipulating you; you are being watched; no one can be trusted - and maybe not even your own eyes. Not too long ago we selected Klute (1971, QFS No. 128), one of Alan J Pakula’s paranoia films of the era or even Francis Ford Coppola’s masterful The Conversation (1974). Blow Out fits right in. But the conspirators here are almost comically incompetent. They hire a … hitman? Or maybe just a psychopath in Burke (John Lithgow). Looking at the entire picture, Burke reveals himself to be utterly terrible at his job. He’s supposed to disable the car with the presidential candidate, but instead he kills him. (The plan, of course, was pretty faulty from the start.) Then he kills the wrong woman who he thinks is Sally. And then – he does kill Sally but gets killed in the end too. That’s not to mention that Burke, for no apparent reason, kills a prostitute in the train station just for fun! This is not the “professional” you should hire when attempting to commit political violence.

In the end, the unseen forces win. Not only did they eliminate the candidate from the contest, but they’ve essentially eliminated all trace back to the conspiracy. Only Jack knows, but he has no proof and is haunted by the burden of being the only one with the truth.

The QFS group mostly agreed that the film would be an unqualified masterpiece had De Palma was able to stick the landing. The final quarter of the film is something of a disaster, which lead us to speculate whether De Palma felt the need to amp up the action given the larger budget he received when casting Travolta in the lead role. For some reason, Jack drives directly through the Liberty Day parade to get to the subway exit to where Burke is heading with the captured Sally. In an attempt to save one person, Jack nearly kills hundreds before crashing into a wall, getting knocked out, an ambulance comes (off screen) and when he comes to, he escapes the ambulance and gets to Sally too late. It’s preposterous and in many ways doesn’t fit the tight thriller that De Palma crafted leading up to it.

The film showed Jack as an intelligent artistic type with a “superpower,” for lack of a better term – to be able to discern specific sounds. The story is setting up for him using this skill to solve the puzzle or to save the day – perhaps by hearing the clicking sound of Burke’s watch garrote, or by being able to hear Sally’s whereabouts more readily. Instead, De Palma focuses on Jack having to overcome past demons by wiring Sally – something he did in the past before he got one of his undercover informants killed. That haunts Jack, and so the story focuses on overcoming that part of his past. He fails with Sally, just as he did before, which led one of us in the group to conclude that the moral of the story is: don’t let Travolta put a wire on you because you’ll end up dead.

It's one of a number of plot and logic holes, including loose ends that never are addressed. The news guy (Curt May), is he on the up-and-up? How did he know all that about Jack? We’ll never know because that doesn’t pay off. How could Jack possibly be left unguarded in the ambulance after nearly running over people in his Jeep and crashing into a department store display? Why would it matter about the dead man’s reputation now that he’s dead? Just to protect his family? And why didn’t the people who were trying to embarrass the candidate simply just go with the usual plan Sally and Manny (Dennis Franz) do all the time – burst through a room and take pictures of the candidate in bed with Sally? Did Sally kill Manny or just knock him out? And so on.

Despite all of the above – including the questionable third act of the story – the film remains an essential piece of filmmaking. The sequence on the bridge alone is worth the price of admission. When Jack discovers all his tape has been demagnetized, De Palma has the camera spinning steadily on its access, panning around the room as Jack gets into a panic, heightening the anxiety. It’s incredibly effective and I found myself feeling the same thing the character felt - which is exactly the goal of a director in telling a story cinematically and I don’t think I’ve ever seen it done quite as well as it’s done here. In the hands of a lesser filmmaker, it would be gimmicky. But here, it’s perfect.

But I would be remiss if I didn’t bring up one particular aspect of Blow Up that’s dogged De Palma in much of his work, and that is his misogynistic tendencies. First of all, Sally is portrayed as an utterly clueless ditz, incapable of fighting for herself and seemingly out of it the entire time. She is so thinly portrayed and not even given a moment on screen for her to grasp that she almost died if it wasn’t for Jack saving her. In the only scene in which Sally shows any depth comes as she’s sharing with Jack her dreams of being a makeup artist in the film business. To which Jack blows her off as unserious and childish. The opening itself, the salacious POV through the women’s dorm ending in the shower, is fun for teenage boys and of course is evocative of those types of slasher pics De Palma may be lampooning, but is definitely on the gratuitous side.

But if you look more closely at this opening section – the final shot is of a naked woman in the shower, as mentioned above. The actress’ scream is inadequate and it’s Jack’s job to fix it. And he does in the final scene of the film – he uses Sally’s final moments of her life that he recorded and puts in the film. The only worth this woman, Sally, brings to the filmmakers is her sound, her primal cry out to the world. And it will live on as coming from the mouth of a naked woman in a shower. For someone like De Palma who delved into the deep psyche of humans and often has darkly sexual storylines, this feels like it’s no accident.

A charitable way of looking at the ending is that this final sound of Sally will haunt Jack him, and will be his torment, and only he will know how she exists forever in this film. The less chartable way of looking at this is that all a woman is worth is to be seen on the screen as sex objects, to be used even in their final moments for entertainment and as a commodity. Perhaps there’s something in between, but it’s bleak nevertheless.

How do we square De Palma? I have trouble with him, to be honest. I love much of his work, but he revels in the profane, the salacious, and seems to be able to only make male characters fully human. (People level this latter critique against Hitchcock, too.) Yet, there is true artistry in his best films. He creates iconic images and uses the language of past filmmakers to his advantage, creating something new and indelible. Hitchcock’s legacy appears in most of his films, but there’s also of course Michelangelo Antonioni (Blow-Up, 1966 for Blow Out), Sergei Eisenstein (from Battleship Potemkin, 1925, for The Untouchables, 1987) and others along the way. Tarantino, for his part, takes inspiration from De Palma and thus the circle of filmmaking continues.

It's hard to place De Palma in the pantheon of great American directors, but he must be among them. And it’s easy to argue that Blow Out is his finest work, warts and all. Perhaps like the filmmaker who crafted it.

Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959)

QFS No. 147 - Kaagaz Ke Phool – which translates to “Paper Flowers” – is known as one of the great films from the Golden Age of Hindi Cinema.

QFS No. 147 - The invitation for July 17, 2024

Let’s complete another chapter in our on-going Introduction to Indian Cinema 101!

Guru Dutt is one of the unheralded filmmakers from India. “Unheralded” is in quotes because he’s quite ... heralded? ... in India. Though recognized as a great in his own country, he never achieved international acclaim in his lifetime the way that Satyajit Ray did, for example. For me, I was first introduced to Dutt’s work about twenty years ago when Time magazine’s legendary film critic Richard Schickel listed Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa (1957) as one of the 100 greatest films ever made. Pyaasa is a classic that’s moving and also has the unofficial Hindi film mandated musical numbers. But the musical numbers in Pyaasa are not superfluous – they serve the story, bringing poetry to life and enhancing the story. His follow-up Kaagaz Ke Phool – which translates to “Paper Flowers” – is known as one of the great films from the Golden Age of Hindi Cinema.

Now is a good time to recap our course materials for Introduction to Indian Cinema. Here are the films the QFS has selected (in chronological order):

1. Apur Sansar (World of Apu, 1959, QFS No. 16) – part of Ray’s “Apu Trilogy” and the origin point of Indian independent and art cinema.

2. Sholay (1975, QFS No. 62) – a glimpse of a big mainstream Indian movie during an era when such films were uninfluenced by global cinema. Also, our first viewing of Amitabh Bachchan, the most famous movie star in the world.

3. Dil Se.. (1998, QFS No. 32) – where we could see the influence of MTV’s arrival into South Asia, in which a movie produced standalone music numbers that felt separate from the main film. Also showcasing the ascension of Shah Rukh Khan as global heartthrob and second most famous movie star in the world.

4. 3 Idiots (2006, QFS No. 118) – closer to present-day Hindi filmmaking ripe with broad humor, earnestness, and adapted from a popular contemporary novel.

5. RRR (2022, QFS No. 86) – example of a regional language film (Telugu) that exploded into the world consciousness, showcasing modern filmmaking India style.

That’s not bad for a four-year, unstructured and barely planned course into the filmmaking of the largest movie producing country on earth!

You’ll notice in the above list that Apur Sansar and this week’s film are both from 1959. But they represent completely different branches of Indian cinema. Apur Sansar is from Bengal and not considered part of the national films of India (which we now call “Bollywood” but is really known as “Hindi Films” you may recall from our previous lessons). Ray’s Apu Trilogy was more popular abroad than in his own country, where he produced and directed from outside of the national movie industry. He is the first known filmmaker to make a successful film outside the traditional Indian movie studio. The independent scene in India remained very thin for the next 50 years, but the Apu Trilogy is where it begins.

Whereas Guru Dutt was already a Hindi film star known all over India by 1959. While Ray toiled as what we would now call an independent filmmaker, Dutt was a studio filmmaker. He operated within the Hindi film ecosystem, casting stars (including himself) but told deeply personal stories in between the songs and the dances. Kaagaz Ke Phool represents our QFS selection from the Golden Age of Hindi Cinema.

And while Dutt made commercially viable films, his personal life was marred by strife. Perhaps the melancholic storytelling he showcased on the screen came from his world at home. Tragically, he died before he turned 40 possibly from an accidental overdose or possibly, he committed suicide. This is his final film as a director (he acted in eight or so more after this) and though his life was short, he left behind an incredibly impressive body of work as a filmmaker. Dutt remains a revered artistic luminary in India and in film circles – both Pyaasa and Kaagaz Ke Phool appear on “Greatest” lists in India and internationally, including the latter once appearing on the BFI/Sight and Sound Greatest Films of All Time list in 2002. I believe India also issued a stamp in his honor as well.

So join us in watching Kaagaz Ke Phool – the first Indian film in Cinemascope! – and we’ll discuss in about two weeks.

Reactions and Analyses:

In Guru Dutt’s Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959), there are a few scenes that concern horses and take place at a horse racing track. For a movie set primarily in the world of the 1950s Hindi cinema industry and very little to do with horses, this feels superfluous. And, for the most part it is superfluous – it doesn’t have much to do with the main storyline. But it pays off in a way later on thematically.

Rocky (Johnny Walker), who owns and bets on horses, reveals late in the film that one of his prized horses had to be shot and killed because it broke its leg and couldn’t race any more. Not much good now, but the horse had made me millions before, Rocky says. So we had to shoot the horse, he reveals, almost as an afterthought.

At the same point in the film, the protagonist Suresh Sinha (played by Dutt himself), a director who was successful and made many hits for his studio, has hit rock bottom. Drinking, depression, and abject loneliness left him a shell of a man – unemployable and forgotten. Not much good now, but this director made them all millions before. Suresh is not being put out of his misery in the manner of a horse, but perhaps he should be?

The metaphor is clear, and it’s brutal. Fame is fleeting and also no matter what you’ve done before or how successful you once were, you end up dead and alone. Which is what happens to Suresh, who, in what is the most savage scene of the film, dies quietly on the soundstage in which he had once flourished. The morning crew comes and finds him dead in a director’s chair, but the producer doesn’t care. He just wants the body moved (“what, you’ve never seen a dead body before?” he shouts) because the show must go on. The camera rises up to the heavens in a wide shot as light pours into the stage from the outside as Suresh’s lifeless body, small in the frame, is carried off.

It’s an incredibly cynical portrayal (and likely accurate from Dutt’s experience) of a ruthless world, specifically the movie industry. The fact that this is in a 1959 Hindi film – a film industry very well known for cheery, elevated and escapist fare – makes it even more surprising. What’s less surprising, perhaps, is that audiences at the time weren’t too keen on seeing Kaagaz Ke Phool, a notorious flop, only to be rediscovered and cherished now. Perhaps that says more about the times we currently live in than the quality of the film itself.

And to that quality – Kaagaz Ke Phool is a stunning masterwork of directing. Someone in our QFS group pointed out that not only do the shot selections evoke Orson Welles – deep focus, wide frames, low angles utilizing Cinemascope lenses for the first time in India – but Guru Dutt himself looks a lot like a young Welles himself. Both were prodigy actor-directors, both fought inner demons. And while Welles lived with his for a long lifetime in which he fought to regain the fame and power he had when Citizen Kane (1941) reached its ascendancy, Dutt’s demons proved too much for him, and instead died before he was 40. Dutt left behind a legacy of classics and a the tragic feeling that we were deprived of more great and meaningful films to fortify the Indian film industry.

It's easy to find parallels between Suresh in Kaagaz Ke Phool to Dutt’s own life. But beyond that, the film is a masterclass in portraying loneliness. Dutt with VK Murthy – one of India’s legendary cinematographers – has Suresh move between shadows and silhouettes, throwing the focus on the background and trusting the audience with extracting meaning from his imagery and juxtaposition of characters in the frame.

Perhaps the most evocative scene comes about halfway through the film. Suresh has discovered and clearly has fallen in love with the luminous Shanthi (Waheeda Rehman), a non-actor who reluctantly becomes a star in his movies. He’s still technically married to Veena (Veena Kumari) but has fallen in love with Shanthi, and Shanthi, has definitely fallen for him. But they can never be together. To portray this visually, Dutt has music playing between the two characters on a darkened soundstage, featuring the now-legendary Mohammed Rafi song “Waqt Ne Kiya Haseen Sitam” which roughly means “What a beautiful injustice time has done (to us).” There are only shafts of light in an otherwise dark space with each going in and out of shadows and light. It begins with his wife Veena in the scene (possibly imagined), looking distraught as the camera pushes in to a close up, cut with a similar closeup of Suresh as well.

Next, in a wide profile angle, Veena and Suresh are on opposite sides of the frame, the light is shining down in a shaft between them. Then, ghost-like, their translucent “spirit” selves separate from their bodies and move towards each other. The spirits come together in the center of the frame, a special effect shot dispatched for emotional utility. Then, Veena walks into a shadow, but when the figure emerges - it’s now Shanthi, the lover he cannot be with, smiling at him as the music swells.

It’s beautiful, it’s magical realism, and it feels as a definitive example of this is the Golden Age of Hindi Cinema. What characterizes the Golden Age of Hindi Cinema? My admittedly scant knowledge is that the Golden Age is this: all the hallmarks of Hindi film as we know now – melodrama, plot contrivances, depths of extreme emotion, goofy comic relief, evocative musical numbers – but told with a level of cinematic artistry and a trust in the audience’s ability to make meaning from the visual language made by the filmmakers. In the decades to follow, it’s clear that many of those hallmarks continue but two aspects don’t as often – the artistry and trust in the audience.

Not to say that Hindi films today aren’t awash with art and color and life – they surely are. But where Dutt uses all the language of cinema through camera, movement, performance, blocking, light, shadow, and nuanced performance (relatively speaking), modern Indian filmmakers tend to rely on spectacle and over-wrought performance and emotion. This is, of course, broad and my own observation as an Indian American filmmaker born and raised outside of that country’s film industry. But to me, it’s clear why so many Indian film goers who are old enough to remember the Golden Age lament the state of modern Hindi cinema. It simply was better in its basic storytelling, if not the technology and craft. Also, note the musical numbers. They express emotion and flow into the story, as opposed to the standalone numbers that follow and become the standard as Indian cinema progresses in the 20th Century.

One thing that was surprising for all of us in the QFS discussion group was how “modern” Kaagaz Ke Phool felt – a movie about movies and movie makers. The opening shots, if you weren’t paying attention, could’ve been out of Welles or John Ford or Michael Curtiz, reminiscent of American cinema of the 1940s. The film, though indigenously India and about India’s own cinema industry, could’ve been very easily the Hollywood of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950) or All About Eve (1950). There’s a timeless elegance to it – and perhaps that, too, is a hallmark of Hindi cinema’s Golden Age.

Dutt suffered from depression and addiction, as is now well known and was perhaps known then, too. He attempted suicide at least twice before his actual death, in which he may have killed himself (or perhaps accidentally overdosed – it’s not known for sure). This internal melancholy may have led to the abundant and drawn-out final quarter of the film where we watch Suresh’s deep and inexorable decline. This underlying melancholy is a feature of what is considered his preeminent classic, Pyassa (1957) which came out before Kaagaz Ke Phool.

Towards the end of the movie, Suresh, now at true rock bottom – an alcoholic shell of himself – has been cast as an extra in a film where Shanthi is the star. When she realizes who he is, she desperately runs after him but can’t catch him, cut off by adoring fans – an echo of a scene with Suresh from the beginning of the film. The song that plays is “Ud Ja Ud Ja Pyaase Bhaware” and in it, the lyrics say “Fly, fly away thirsty bee. There is no nectar here, where paper flowers bloom in this garden.”

Perhaps Dutt is saying here, as one QFSer pointed out, that there is no glory here in this world where things appear beautiful, like paper flowers, but it’s all an illusion. Paper flowers and fame are not real, will not give you nectar. If you want true meaning, true love, true fulfillment, then you need to seek it somewhere else.

If that’s truly what the filmmaker intended, then this sequence, this final sequence in this master filmmaker’s final film, is a cry for help, placed in a beautifully downcast work of true art. Not all films from the Golden Age of Hindi Film have endured in this way, and perhaps it’s because Dutt placed his finger squarely on something universal, deep, tragic, and true.

Death Race 2000 (1975)

QFS No. 146 - The late great Roger Corman produced this film about a dystopic, mayhem-ridden future. And I, for one, have been keen on seeing it. It takes place in the distant future, the year 2000! What will life be like then? Who knows! Well, the late great Roger Corman will tell you!

QFS No. 146 - The invitation for June 26, 2024

The late great Roger Corman produced Death Race 2000 set in a dystopic, mayhem-ridden future. And I, for one, have been keen on seeing it for some time. It takes place in the distant future, the year 2000! What will life be like then? Who knows! Well, the late great Roger Corman will tell you!

In Death Race 2000 you’ve got the red-hot stardom of David Carradine to contend with alongside upstart nobody Sylvester Stallone. Made on a Corman-style budget, this feels like an even more appropriate Corman selection than our previous one, X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (1963, QFS No. 89). Corman directed that masterpiece himself. This one, he produced it on his B-movie assembly line and is one of the films that actually (sorta?) penetrated into the broader mainstream.

And this is our first return to a Corman film since the legend passed away last month. Let’s honor him by easing back on our critical thinking skills a touch and watch one of his classics. Kick back, relax, and watch the soothing tale that I’m sure is at the heart of Death Race 2000.

Reactions and Analyses:

There was something in the air in the mid-1970s. Part of our QFS discussion about Death Race 2000 (1975) debated what could be the reason for the glut of post-apocalyptic films in the 1970s and into the early 1980s.

The filmmakers of this era grew up as children with memories of the horrors and heroism of World War II and came of age in the Cold War, a time fraught with the very real possibility of global extinction from nuclear weapons. In the 1970s, The studio system no longer had a stranglehold on filmmakers and a parallel film track from auteurs was starting to penetrate the mainstream.

So given some of these conditions, we see films like A Clockwork Orange (1970), Logan’s Run (1976), Soylent Green (1973), Mad Max (1979) and its sequels, Omega Man (1971), Rollerball (1975), Planet of the Apes (though from 1968, the film franchise continues in the ’70s), and perhaps you could argue THX 1138 (1971) and Stalker (1979, QFS No. 25) as well. And of course, Death Race 2000.

Many of those films are attempting to make a commentary about something – overpopulation (Soylent Green), reliance on fossil fuels (Mad Max), nuclear war (Planet of the Apes, presumably and maybe Stalker), totalitarianism (THX 1138).

And then you have commentary on violence in society and our fascination with it (A Clockwork Orange), how we’re inured to it and, in the case of Rollerball and Death Race 2000, how that fascination is literally turned to sport.

How much social commentary Roger Corman and director Paul Bartel are actually interested in is probably very little. The film is perhaps best summarized as one QFS called: the perfect hangover movie to watch after waking up at noon after a night of drinking. This is, of course, high praise.

The premise of the eponymous “death race” is … simple? Simple, but convoluted. Annually, as a way to appease the masses, racers speed across the continent racing from New York to Los Angeles while trying to kill as many people as possible with their vehicles. Killing the elderly or children will give racers the highest number of points. But also – whoever finishes first wins? It’s not entirely clear.