Forbidden Planet (1956)

QFS No. 119 - This is going to be an interesting one in that Forbidden Planet is (A) adapted from William Shakespeare and (B) we’ll be forced to take Leslie Nielsen seriously, he of Airplane! (1980) and the Naked Gun franchise fame.

QFS No. 119 - The invitation for August 9, 2023

This is going to be an interesting selection for us at Quarantine Film Society. Forbidden Planet is (A) adapted from William Shakespeare and (B) we’ll be forced to take Leslie Nielsen seriously, he of Airplane! (1980) and the Naked Gun franchise fame.

I’ve wanted to see this film for a little bit and I thought it’s time to return to pure escapist fare from an era before the special effects were super special but definitely inventive.

Join me in seeing Forbidden Planet and we’ll discuss!

Reactions and Analyses:

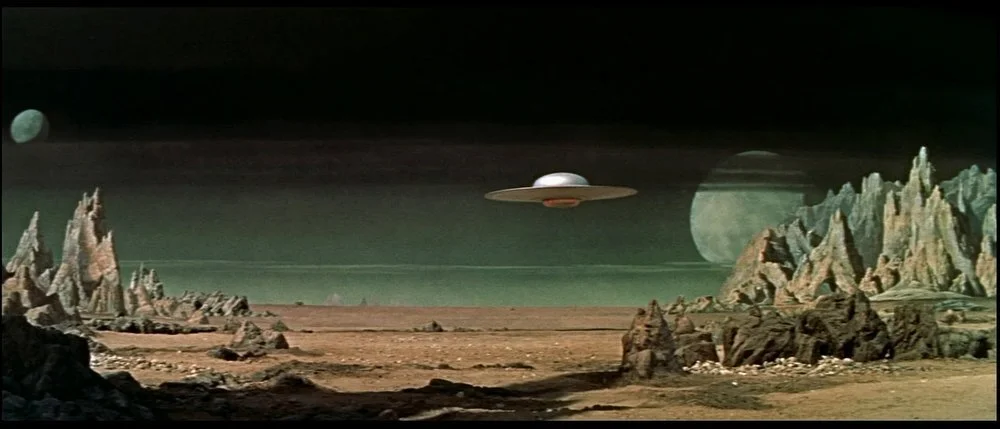

Watching Forbidden Planet with the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to see how influential it was to the next generation of filmmakers who expanded the possibilities of science fiction motion pictures. The entire film could be an episode of Star Trek, complete with the confident (and perhaps a touch pompous) captain and a mission by an Earth space agency in a time of great space exploration. As far as I can tell, this is the origin point of “hyperdrive” to propel a mission into space. Add a human-like docile Swiss-army-knife of a robot Robby and you get the serve as prototypes for hyperspeed, C-3PO and R2-D2 from the Star Wars universe all in Forbidden Planet.

The world created by Fred M. Wilcox in Forbidden Planet is vibrant and mysterious. He contrasts the drab greys and metallic colors of Commander Adams (Leslie Nielsen)’s crew with the pastels of the landscape and the lush tones of Dr. Morbius (Walter Pidgeon)’s home and interiors. Altaira (Anne Francis) prances in clothes that deliberately angelic and pure. The film, though science fiction, is a mystery set in a truly new world.

For all of the beauty in the world of Forbidden Planet – of which there is plenty – there lies at the center of the story a heady concept at its heart. Morbius was shipwrecked on this planet two decades earlier and is the only survivor, along with his daughter Altaira. In that time, they discovered remains of the Krell, a highly advanced species who became graceful geniuses and harnessed power in ways that dwarfs what humans have been able to do. Morbius, by using their machinery, has expanded his own mental power as well.

However, the Krell are gone. And the thing that killed them might be the very thing that wiped out Dr. Morbius’ fellow travelers two decades earlier – an unseen plague. That unseen plague steadily starts to eliminate members of Adams’ crew. So that’s the central mystery of the film. Who, or what, is the invisible monster on the island and can it be stopped?

At first, Morbius seems set up to be a mad genius villain. Yet, he’s perplexed by the monster on the island too. At first we’re led to believe it’s Morbius who is somehow responsible, that he’s cruelly eradicating all of his fellow Earthlings. And while it doesn’t lead us down that path too far, it does something surprising. The monster is Morbius. It’s his id – the part of his subconscious that is primal and instinctual, as described by Dr. Sigmond Freud. Fear, hunger, hate, shame – this creature is a manifestation of Morbius’ id.

And what brought about anger and fear from his id to create this creature? The visitors from Earth leering at his daughter. He fears her leaving, of becoming a woman, of choosing to go with Commander Adams and his crew and leaving him behind. And to be fair to Morbius, the men are very creepy. All of them are fawning over Altaira, with Adams going so far as saying that, well, what do you expect – you’re dressed like that and we’ve been trapped on a spaceship together for many months.

Ironically, it’s this aspect of the film that’s most dated and not the visual and special effects - it’s this obvious misogyny, tolerated or even accepted when the film. And moreover, she has never even seen a man who wasn’t her father, so how could she possibly know how to behave around them, even if Adams was right?

For their part, the visual and special effects hold up and are incredibly … effective … and at times spectacular. Perhaps except for Robby the Robot. Who everyone loves but definitely wouldn’t stand a chance against the likes of even the most simple of droids from the Star Wars Universe. (We mean no disrespect - Robby is a legend of filmand television.)

But the men do fall for Altaira and she for Commander Adams, hence justifying Morbius’ fears. As one QFSer put it in our discussion, it’s like a frat party just landed next to a house with a guy and his pretty daughter. Looking at it from this vantage point, I couldn’t help but feel like I understand Morbius – he’s acting out of primal need to protect his daughter from these creeps. So the film is heady and surprising in that way. There’s no traditional villain; Morbius is unaware of what he’s done to create the invisible creature from nightmares. However, the film doesn’t present Morbius in a sympathetic manner, focusing more on the hubris of a man who thinks he’s above it all since he unlocked higher intelligence. But all he’s done is push his baser instincts aside and created a monster.

This is quite difficult to follow and untangle at first since it’s all done in dialogue with one small twist: Robby is unable to shoot the creature. Because the creature is Morbius and Robby has been programmed never to harm a person. This is the one visual way Morbius - and the audience - finally understands that the creature is from Morbius’ psyche. Adams explains it all but it’s difficult to comprehend while the id monster is crushing doors and bearing down on them. In some ways, though, the scariest creature is one you can’t fully see - and this one, we only see once while it’s caught in the electric fence. That one time is terrifying enough and gets great mileage for the remainder of the film.

Despite some of these gaps and missteps, Forbidden Planet is incredibly enjoyable. Robby the robot is actually too great of a robot. Any robot who can both make a dress from scratch as if putting in A.I. prompts or can make 60 gallons of bourbon after “sampling” some of it (and burping), is a dream come true. He drives like race car driver and has gentlemanly manners to match. If anything, Altaira should be paired with Robby the Robot.

Ten years after Forbidden Planet Gene Roddenberry’s series Star Trek debuts on television, and eleven years later, Lucas makes Star Wars (1977). Going back to Forbidden Planet after seeing those two expansive successors feels like visiting an original text. Science Fiction has been around from before the invention of the motion picture. And once the motion picture was invented, science fiction became one of its primary genres. Yet, it’s easy to see how our two biggest tentpoles for Science Fiction began here, with Forbidden Planet, long ago on Altair IV in a galaxy far far away.

Honeyland (2019)

QFS No. 5 - In keeping with the randomness of the movie selection, it’s time to switch gears and watch a documentary feature film because who’s there to stop us? Though I’ve made a few of them, I’ve never selected a documentary to watch in any of the predecessor film societies before QFS. But Honeyland (2019) I’ve had on my watch list from last year so I figured why not.

QFS No. 5 - The invitation for May 27, 2020

In keeping with the randomness of the movie selection, it’s time to switch gears and watch a documentary feature film because who’s there to stop us? Though I’ve made a few of them, I’ve never selected a documentary to watch in any of the predecessor film societies before QFS. But Honeyland (2019) I’ve had on my watch list from last year so I figured why not.

I know very little about Honeyland other than the raving reviews I heard from trusted sources. I would’ve known even less but for the first time I permitted a guest selector to join me in choosing this week and I watched the trailer with her. Valarie found this trailer to be the most compelling of the five films I narrowed down for her.

So there you have it – a peek into the rigorous selection process that happens here at QFS Studios and Educational Institution for the Barely Stable. Also – not that this should be a sole reason you watch anything – this film won thirty four (34!) awards last year.

So this week we’ll watch this nonfiction film and apply our rigorous, unflinching, inebriated evaluation of its narrative as we would with any film. Join us if you can!

Reactions and Analyses:

Written in March 2024 - Honeyland (2019) was a perfect selection for our first documentary film selection for the nascent Quarantine Film Society back in 2020. To date, we’ve only selected three nonfiction films, and all three have crossed over from documentary into traditional narrative film in some way. Our most recent documentary selection, last week’s 20 Days in Mariupol (2023), won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature Film, just as Honeyland did four years ago. 20 Days in Mariupol is an action-driven film that could easily be a narrative fiction film if it wasn’t crafted as urgent reporting from the frontlines. Flee (2021), was also nominated for a Doc Feature Oscar and though it didn’t win it similarly crossed boundaries as both nonfiction and animated - a feat so rarely pulled off.

Both of those QFS selections are documentary films that are not pure docs in the way that nonfiction films had historically been considered. The deft hand of the filmmaker was evident in crafting the story, and it very much feels like a “movie” rather than a “documentary.”

And while the filmmakers have made themselves virtually invisible in Honeyland, the film too defies the conventions of nonfiction storytelling. The narrative storyline of the film feels deftly crafted as a scripted tale - a woman, using an ancient craft, struggles against nature and time to provide for her family as she attempts to survive the encroachment of a modern society. If you squint just hard enough, you could imagine this film told in black-and-white in the 1960s as a neo-realist classic.

Except that it is “real” and not “realist.” Hatidze Muratova is one of the last keepers of wild bees, selling honey to local markets. Newcomers, an itinerant family, settle next door and while it starts off well - havoc ensues. This setup is a time-honored narrative convention - a person’s sense of normalcy is disrupted, setting off the story and a chain of events that test the protagonist. This is why this film was perfect for a group of filmmakers who mostly in the world of fiction. Not to mention, the cinematography was stunning and evoked a certain movie-like quailty.

I didn’t take detailed notes of our discussions when the QFS first started, but I remember one aspect of our analysis, and that was the role of the filmmaker. Some questioned whether the filmmaker has a duty to intervene or assist the subject if that subject is in danger. In particular, the boy from the family nearly drowns in a river. Were the filmmakers supposed to help? Would that violate a code of ethics? Or is there a greater moral obligation and duty to save the child? The child survives but it brought up questions that you don’t get when you watch a scripted film. There are many skeptics who question how much is real and how much is staged - another dimension of nonfiction filmmaker that does not come up for those of use working in fiction.

When we watched the film, the world was a strange place. Everything was shut down. We though we had to scrub our groceries and local officials shut down walkways and public spaces even though they were outside and could offer respite from our homes. Social order and democracy itself seemed to be crumbling all around us. So perhaps it was some comfort to watch a film taking place in the glowing sun of Macedonia and to hear a woman say to her bees “half for you, half for me.” If only to transport us elsewhere, which is what the best films - fiction or nonfiction - can do.

Blood Simple (1984)

QFS No. 4 - I have some peculiar blank spots in my film knowledge, many of them shameful for a filmmaker. Here’s one: I admit it, I have never seen Blood Simple, first film of the Coen Brothers (Miller’s Crossing, Big Lebowski, The Man Who Wasn’t There, No Country for Old Men, Fargo, O Brother Where Art Thou, A Serious Man, True Grit.)

I listed all those other films in the parenthesis just to prove that yes, I do quite love their filmmaking and movies and yes I’ve seen all of those, you jerk. I just can’t explain it, but by chance I have never seen the film that put them on the map.

QFS No. 4 - The invitation for May 20, 2020

I have some peculiar blank spots in my film knowledge, many of them shameful for a filmmaker. Here’s one: I admit it, I have never seen Blood Simple, first film of the Coen Brothers (Miller’s Crossing, Big Lebowski, The Man Who Wasn’t There, No Country for Old Men, Fargo, O Brother Where Art Thou, A Serious Man, True Grit.)

I listed all those other films in the parenthesis just to prove that yes, I do quite love their filmmaking and movies and yes I’ve seen all of those, you jerk. I just can’t explain it, but by chance I have never seen the film that put them on the map.

BUT – and this should give me some snobby filmmaking cred to help repair my damaged reputation from revealing the above – I did see A Woman, a Gun and a Noodle Shop (2009) which is the MANDARIN LANGUAGE REMAKE with GERMAN SUBTITLES in a theater at the BERLIN FILM FESTIVAL. Take that, you judgmental fellow film snobs…

Regardless, I’m looking forward to watching what I assume and hope is an English language production. Because I can’t read German or follow Mandarin. And looking forward to finally watching the biggest part of the Coen Brothers’ origin story as filmmakers.

Reactions and Analyses:

After the opening preamble, the first scene shows Abby (Frances McDormand) driving with Ray (John Getz) in the rain. For maybe two minutes it’s a two-shot from behind the driver and passenger, the rain is pouring down the windshield and so pitch black that you can’t see anything outside the window and barely anything inside the car. When headlights from outside the window flash up, blinding the frame, there’s a moment to readjust your eyes to the scene - which remains the same two-shot.

There’s something about this beginning that is not only ingenious from a filmmaking standpoint but also provides a set up for the story. The two are talking about a having gun that was a gift from her husband, that she’s leaving her husband (who is not the driver), and the man who is driving works for the husband. The setup is classic - gives us an expository framework, explains some of the setup, sets a mood, and suggests something ahead. The two aren’t yet having an affair but they’re about to start one.

And while that’s all excellent storytelling, the ingenuity of the Coen Brothers’ opening here is in the filmmaking. The filmmakers didn’t have a lot of money - it’s their first film and this is a bare-bones independent production in which they had to virtually panhandle for to raise funding. This is a very inexpensive way to shoot this scene. The car is almost certainly not moving, water is probably being sprayed on the windshield while someone on the crew shakes it. Someone else is mimicking street lights. Add rain sounds, car noise and haunting music and you can pull this scene off. The remaining elements - a shot of the moving road that precedes this one, a shot of the bumper coming to a stop on the road - and you’ve got a low-budget, high-impact scene and the audience will feel as if they were in the car with these two characters, moving through a rainy Texas night.

Of course, in addition to production cleverness, you also need the artistry. The artistic filmmaking that follows is entirely contained within the first five minutes of the film and continues apace throughout. About halfway through the film, after Ray discovers that the husband Julian (Dan Hedaya) is dead and decides to hide the body - that sequence is entirely without dialogue for 18 minutes. And it is textbook suspense storytelling. Ray makes the discovery, then makes a decision, then has to prevent the other employees at the bar from discovering the body. He has to get it out, dump the bloody clothes in the incinerator, has to dispose of the body. But the body isn’t a body - it’s Julian, and he’s come back to life! He now has to kill a dead man, but a semi truck almost smashes into them! Then he finally gets the body into a hole but there’s enough life in Julian that he raises a gun but there are no bullets and Ray gently takes the gun from him. He makes the harrowing choice to bury Julian alive - a choice that haunts Ray throughout the remainder of the film.

It’s the meat of the film and it’s just on the border of believability (that Julian could have lasted that long), but that’s the one thing that requires a tiny suspension of disbelief. Everything else seems entirely plausible - the messiness, the panic, the confusion, the opportunity. If movies have taught us anything, it’s very difficult to dispose of a corpse. And especially difficult if that corpse isn’t yet a corpse.

The ambient sounds, the sparse use of music, the darkness and shadows, lit by headlights or neon signs in the bar or the light from the incinerator - all of this is textbook filmmaking. This 18-minute sequence should be required study for all filmmakers. The choice of shots, when to move the camera, when to be on a close-up, the framing relative to the horizon, the staging of the actors and action. The film is a neon-inflected film-noir, with cigarette smoke floating up in soft purples and blues, with a pace that keeps moving without feeling rushed. Blood Simple feels like the assured hand of an expert filmmaker, not first-timers as Joel and Ethan Coen were in 1984.

People, rightly so, talk about the final shot of the film of the dripping faucet as one of the enduring images of the film. I’d argue this opening sequence holds equal significance artistically and narratively.

One of the fun things about watching Blood Simple is knowing that this is the starting point of the Coen Brothers, their origin story. People who get in over their heads and try to navigate criminal behavior without any real ability to do so. Characters like Private Detective Loren Visser (M. Emmet Walsh) who totally lack self-awareness and usually morals. And some John Carpenter-esque camera angles - the super-wide angle lens fast-moving Steadicam shots or objective angles on a bloody finger or feet walking.

Blood Simple does make it difficult for you to root for any one in particular. Everyone is a sweaty, greedy, selfish maniac. Perhaps Abby - but she’s no saint either. She’s This is a hallmark of the Coens as well. They’re not in it for heroism or a clean ending, not in the way Hollywood has conditioned us to expect. They show people - at times overtly quirky folks but usually just ordinary people - in all their messiness, dealing with primal human emotions. Love, pain, hatred, fear, paranoia and, very occasionally, joy.

There’s something oddly pure about Blood Simple - and I don’t mean the plot of course. The craft is expert level but the story is simple despite the twists and complexities of the relationships. From the vantage point of forty years after this Coen Brothers origin story, there’s a parallel with Wes Anderson. Not stylistically, of course, but in how their films evolve. There’s a “Coen Brothers” film that becomes iconic, the way there are “Wes Anderson Films.” The characters behave in a way you expect them to behave in a style you expect - that’s what makes Anderson and the Coens have a similar feeling, career-wise, from how I look at it today.

For the Coeans, it’s goofy or quirky characters in bizarre situations that can range from realistic to overtly stylized. And at the root of it is money. People need money and are thrust into situations where ill-gotten money gets people in trouble and it spirals out of control. The Big Lebowski (1998), Fargo (1996), No Country for Old Men (2007), Raising Arizona (1987, but the money is kids), Burn After Reading (2008), The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001) - all have something to do with money and usually people who don’t have any but need some and do something they usually wouldn’t to get it.

I’m not saying this is a bad thing in any way. A generation earlier thoroughly enjoyed an Alfred Hitchcock film in much the same way - suspenseful, twists, ordinary people getting in over their heads. And now, there exists a Coen Brother Movie archetype. There wasn’t one in 1984. So I try to put myself in that time when watching Blood Simple, of seeing a Joel and Ethan Coen film for the first time without any additional knowledge of what are the expected beats and twists one might expect in one of their films. If you look at it that way - Blood Simple is nothing but a dark, thrilling, suspenseful, film - an explosion of film talent splayed across the screen that, hopefully, continues to endure well into the future.

The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1943)

QFS No. 3 - Preston Sturges is one of my favorite American filmmakers of the pre- and early post-war era. His Sullivan’s Travels (1941) and Hail The Conquering Hero (1944) are exceptional works of writing and subtle-to-overt social criticism through satire – especially during the studio system era.

QFS No. 3 - The invitation for May 13, 2020

Preston Sturges is one of my favorite American filmmakers of the pre- and early post-war era. His Sullivan’s Travels (1941) and Hail The Conquering Hero (1944) are exceptional works of writing and subtle-to-overt social criticism through satire – especially during the studio system era. A handful of us were fortunate to catch Hail The Conquering Hero in the theater here in LA for our predecessor Wednesday Night Film Society get together at the New Beverly Cinema several years ago.

The Miracle at Morgan’s Creek has been on my “to watch” list for some time, so I figured let me use this opportunity in quarantine to encourage everyone to embrace their primal love of black and white cinema. Also this is probably the exact opposite type of film than the previous week. (We’re going to swing back and forth a lot with these selections!)

Join us if you can – details to follow.

Reactions and Analyses:

The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1943) is a surprisingly subversive film. At the center of the story is Trudy (Betty Hutton) who is pregnant and doesn’t know who the father is. But she knows it’s a soldier because she was at a wild farewell party for a group of soldiers heading off to fight in World War II and had hit her head on a chandelier. She believes she married a soldier but doesn’t even know his last name for sure so they can’t find him.

Just stopping there - this is extraordinary. Think about 1943 and 1944 when this film is released by Paramount Pictures. How could a major movie studio release a film with this borderline blasphemous plot during the height of World War II when the nation was mobilized in unwavering support for the war effort and American soldiers conscripted to fight overseas? The premise suggests that a woman was so blackout drunk at a party with soldiers, enjoying the company of one or more of them, then got pregnant and has to figure out what to do now.

Throw in the hapless Norval (Eddie Bracken) who throws on a uniform as if to solve the problem as they fake a marriage, where things continue to go awry, and you take it from tragedy to comedy really quickly, with moral questions at its center.

The only filmmaker of that time - especially for a comedy - who could credibly pull this off is Preston Sturges. A true auteur before the word ever came into being even in France, Sturges was writing and directing his own films with his own unique voice. You can look no further than the terrific Hail the Conquering Hero (1944) from this same year (also starring Eddie Bracken) which skewers the idea of war heroism. There, Eddie Bracken’s “Woodrow” is discharged from the military after only a month, but a small lie - that he fought abroad - spirals out of control as everyone treats him as a returning hero. He’s suddenly the toast of his home town, rekindling an old love, even picked to run for mayor.

Here, in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, there’s a similar theme - this idea that soldiers are unassailable demigods and not fallible humans. That war and military service is the measure of greatness.

By the end of the film, Trudy gives birth to six boys in a truly wild delivery room sequence that features a harried Norval and a frantic doctor. The news makes it around the world - both the fact that someone gave birth to six children but also that they were all, miraculously, boys. This is portrayed as a sign of American virility and prowess, of American might and righteousness. It’s wacky, it’s nonsensical, and the time frame of it all makes no sense. But it’s the perfect conclusion to a Sturges film.

One QFSer brought up that this is all tongue-in-cheek. Sturges is saying that all of this American moral superiority is nonsense and deserving of ridicule. Or at the very least, deserving of at least a mirror to show ourselves how shallow and self-delusional it all really is. Sturges’ tone borders on sarcastic, but it’s not sarcasm exactly. It’s farce - social criticism covered up by farce. Whether it worked on that level for audiences at the time is perhaps unclear now, but it certainly clear upon watching in 2020. The brilliance of Sturges here, and in all his work, is how it endures even though it was meant to probe the cultural and social norms of the time.

Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985)

QFS No. 2 - As perhaps with you, “thunderdome” is my stand by phrase for anything that has no rules with chaos as its only governing principle and where destruction is the norm. It entered the zeitgeist after this film and entered our collective lexicon even if you haven’t seen the movie. Related point – if you come to our home you will see that we have our fenced-in children play area in our main room that we have dubbed “Baby Thunderdome.” No holds barred, very few rules and the only directive is “to survive.” So far, both children have. But for how long?

QFS No. 2 - The invitation for May 6, 2020

SR note: Since this was only the second time we had a virtual film chat, the invitation format had not been standardized as this was a novel concept for all of us. Enjoy!

Thank you to all of you who joined our first ever Quarantine Film Society get together last week. It featured filmmakers, filmmaker adjacents, and civilians. It was a lot of fun and technology only failed us (well just me) once.

But it was a success in that we talked about the movie, about filmmaking, and went off topic a reasonable amount of times. So wonderful to see you all who joined – we spanned three time zones!

So this week, let’s pick something perhaps totally opposite from the elegant, graceful, fantastical imperial China depicted in last week’s selection. Since we’re all living in the apocalypse or perhaps the early stages of it, let’s watch something informational and perhaps a little cautionary.

Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985). Yes.

Okay, two confessions: first – I truly love Road Warrior and Mad Max: Fury Road. Second – I have never seen Thunderdome save for a few glimpses on WGN while growing up in Chicago.

As perhaps with you, “thunderdome” is my stand by phrase for anything that has no rules with chaos as its only governing principle and where destruction is the norm. It entered the zeitgeist after this film and entered our collective lexicon even if you haven’t seen the movie.

Related point – if you come to our home you will see that we have our fenced-in children play area in our main room which we have dubbed “Baby Thunderdome.” No holds barred, very few rules and the only directive is “to survive.” So far, both children have. But for how long?

One of my crowning achievements as a parent is to make the term “thunderdome” part of our family’s daily vocabulary. Truly, nothing will top that. It has become canon.

Anyway, I really admire George Miller’s commitment to this kinetic and unflinching version of the apocalypse and I want an excuse to watch it – and to help prepare for our real-world version thereof. And also I’m looking for additional tips to make our baby version of thunderdome approach this on-screen version even more.

So here it is. Join us if this crazy departure is worth your time.

Reactions and Analyses:

Written in December 2023 - In hindsight, this seems like an odd choice for our second film. Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome is not exactly a work of art that has endured the test of time. (You could argue that The Road Warrior, 1981 and Mad Max: Fury Road, 2015 have.) But in May 2020, it definitely felt like we were on the brink of an apocalypse and, well, let’s prepare ourselves with the insights from a film that shows our possible near-to-distant future.

Why is this film so vastly inferior to its predecessor and its successor? It has the same basic set up and premise as those films do - a single man, in a post-apocalpytic wasteland, looking out only for himself, finds himself bound by his moral code to care about others and to guide them in their quest - despite his desire for solitary survival.

Not knowing anything about the film other than the word “thunderdome” becoming a part of the standard English lexicon and that “thunderdome” appears in the titles, it seemed as if Thunderdome would have a more definitive narrative role in film. The title prepares the viewer to imagine that that Thunderdome will perhaps represent a climactic or thematic aspect of the film. “Fury road” certainly does - a mad escape route, a main thoroughfare literally and figuratively for that Mad Max movie.

But here, Thunderdome happens almost at the beginning of the film. Very early on, Max (Mel Gibson) has to fight in this gladiatorial arena against Master Blaster (Angelo Rositto, Paul Larsson and Stephen Hayes - which is amazing that it took three people to portray this wild creation). Ultimately, Max survives, does not kill Master Blaster, but Aunty (Tina Turner) wins and exiles Max into the Wasteland.

Brief aside about Thunderdome - the set piece is a true stroke of George Miller genius. It’s perfectly conceived, and I mean that in a filmic sense. It’s entirely impractical as a way of adjudicating disputes and is almost illogical in how it could’ve come to be. Setting aside that, it’s a perfect terror-dome by which all other terror-domes are measured - the art design, the filmmaking, the novelty of it - this is all pure Miller.

The rest of the film doesn’t really follow suit, in part because when you showcase your most ingenious idea up front, it’s hard to go anywhere after that. There are exceptions, of course - you could argue that the battle on Hoth in The Empire Strikes Back (1981) puts its greatest set piece up front with the battle on the snow planet to start the film. Following that model, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome would have to have its emotional “set piece” at the end. It’s not a film that sets up an emotional set piece, and certainly not in the way The Empire Strikes Back does of course.

The chase sequence on the railroad tracks is also pretty spectacular so there is a companion action piece in the film. But our criticism of the film is certainly not in its action pieces, which remain top notch even when seeing the film thirty-five years after its release.

It’s entirely possible that this film is far too unusual compared to the others in the series. Road Warrior is straightforward in its concept, as is Fury Road, in its basic plot. But the plot in Beyond Thunderdome is convoluted. The film focuses far more on the world created than the plot. So then you’re forced to reckon with how unusual it all is. In that I mean - let’s start with Bartertown. It’s powered by literal pig shit. The Underworld is really a disgusting place that, even now, I’m wincing just picturing it. The interlude of the tribe of children and teenagers is long and trying to be overly sentimental but it’s odd and defies logic. They are descendants of a crashed 747 when the apocalypse began, which is a truly inventive creation - but thinking about it for a few seconds it doesn’t really make sense how they exist. I know that all of the Mad Max films stretch credulity, but there are aspects in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome where the stretch is either a bit too much or there are one too many. Throw in a weak plot, then you have a recipe for a film with astonishing visuals but very little else.

I don’t think we gathered valuable insights into what to expect or how to survive our own seemingly inevitable apocalypse by watching this film. Still - no one pictures a post-apocalyptic world as inventively as George Miller. This film reminded us just how difficult it is to create that world and how masterfully he has done it in the other iterations of the Mad Max saga.

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000)

QFS No. 1 - The invitation from April 29, 2020: SR Note: This email invitation contains the QFS origin story - our first ever email sent out to the group that would become Quarantine Film Society. The format became slightly more standardized as we went along. Enjoy.

QFS No. 1 - The invitation for April 29, 2020

SR Note: This email invitation contains the QFS origin story - our first ever email sent out to the group that would become Quarantine Film Society. The format became slightly more standardized as we went along. Enjoy.

If you are receiving this this email electronically that means (a) society has not fully collapsed and technology still exists and (b) you have been on the list of our “monthly” gathering in LA, Wednesday Night Film Society. Or (c) you have just now been added to WeNiFiS’ risk-averse cousin …

Quarantine Film Society!

The original premise of WeNiFiS was to get us out of the house to watch a movie in the theater and then talk about it afterwards. A way to see movies in the way they are meant to be seen and also an excuse to hang out in the capital of MovieTown. We watched one (1) film this way in 2020 (Parasite) before the plague stretched across the lands. So alas no more theater outings until the plague subsides. But we can still talk … at least until the virus further mutates and renders us speechless. UNTIL that happens, here’s what I’d like to try for QFS.

I’ll pick a film for you to watch at home or in you bunker. It will either be a film recently released or perhaps we’ll revisit an old classic. It may or may not be a film you have already seen. But that’s okay – revisiting a film is wonderful and I find myself doing that so rarely these days. It’s nice to cook comfort food sometimes while also trying to bake something new.

Anyway – after I’ve emailed the choice of film, you have essentially a week to watch it at your leisure on whatever streaming service you can find the film (or DVD/BluRay/VHS/16mm if you happen to own it). Then on, at the listed time and date, click on the provided Zoom link and we shall discuss it in a civilized manner at first followed by childish name calling and eventually direct threats.

So think of it as a book club for movie nerds. The Zoom get together will give you an excuse to wear a shirt that day, but depending on the framing of your device you could probably still not wear pants should you so choose. You could also remain intoxicated regardless of framing.

Speaking of – since we won’t be meeting at a bar or restaurant like we usually do after the movie, everyone is encouraged to drink at home and turn the music up a little too loud so you have to lean in to hear each other speak.

ENOUGH WHAT MOVIE ARE WE WATCHING?

Let’s escape the rapidly encroaching walls in the confines of our homes and disappear into - Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon (2000), directed by Ang Lee.

It’s hard to believe it’s been twenty (!) years since Crouching Tiger was in the theater. I saw it in the first few months after I moved to Los Angeles in 2000 at an IFP screening, and have seen it maybe one more time since. Thinking about it feels comforting and appropriately escapist, so I figured now is a good time to revisit it. I’ll say no more if you haven’t seen it so we can discuss then.

I’ll send a reminder and I guess a Zoom link next week some time. Though I’ve never hosted a Zoom meeting so bear with me. Also – this may or may not work but hell, it’s worth giving it a try. At worst, you’ll have put on a shirt that day.

Stay safe, be well, disinfect everything.

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) Directed by Ang Lee.

Reactions and Analyses:

I didn’t write extensive notes during this first discussion, but I’ll reflect on the time and the nature of the get together, as well as some details I remember from that conversation. As part chronicle of our times and part film analysis, this one will lean a bit more into a chronicle of our times.

Zoom was a relatively new tool for many of us. My wife had been using Zoom for a year at this point to communicate with her staff in other cities. I had been on it a few times after everything shut down in mid-March, but mostly to talk with friends about how their lives had changed and what their fears were a few weeks into the shutdown.

I invited people to watch Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon (2000) and to join me on Zoom to discuss. Our turnout was incredible. This was before I kept track of the numbers because I thought I was only going to do this once, but we had I believer more than two dozen filmmakers join the conversation. It’s not just because of the film or anything I did - everyone was yearning for human connection outside of their homes. It was still early and we hadn’t yet paced ourselves or gotten used to being isolated at home.

As for the film - it remains a stunning piece of filmmaking. I had not watched it in many years, but all of it showcases a filmmaker at the very apex of his powers - the cast, the filmmaking craft, the storytelling, the mythology created, it’s all riveting. It feels like a fable, like a tale from antiquity told anew on screen. The fight in the treetops is a masterpiece. Michelle Yeoh (as “Yu Shu Lien”) is as magnetic as ever on screen, as is Chow Yun-fat ("as “Li Mu Bai”), and Zhang Ziyi (as “Jen Yu”) is perfectly cast and her heartbreaking leap at the end is still wrenching to witness.

Ang Lee remains one of the filmmakers I most admire. After Life of Pi (2012), an essay he wrote went around about how he nearly left filmmaking early on to get his Masters in computer science or something like that, because he was failing to break through. His wife found his acceptance letter to the program and confronted him, imploring him not to give up on his dreams. He threw away the letter and did just that, to the good fortune of us all. It’s something I think about often that keeps me going as well.

His directing is what I call “invisible.” He tells the story the best way he can with the tools of a filmmaker. He doesn’t have a style that you can point to the way a David Fincher or a Wes Anderson does. For an Ang Lee film, the story comes first - what is the best way to tell this story - the style comes naturally from that.

In addition to that - here’s an Asian filmmaker who has made films that reflect his identity but also others that have nothing to do with being Asian. He directed The Ice Storm (1997) for crying out loud - a film with all white people fraying at the seams. And it’s excellent. He directed a film about two men who love each other in a time when they can’t in Brokeback Mountain (2005) and won an Oscar for directing it. What I mean to say - he’s a filmmaker who is treated as a filmmaker, not an “ethnic” filmmaker. This, to me, is the highest praise for someone like him - and like me. As a South Asian American filmmaker, I always strive to be recognized first and foremost for the quality of my work and not who I am or what I look like. I know that’s true for most all of us, and Ang Lee represents that ideal.

Anyway, we had a fruitful discussion that was a lot of fun and gave me the idea to keep doing it. I had no idea it would continue for years - both the group and COVID. Here’s hoping the group endures longer than the pandemic.