Brazil (1985)

QFS No. 158 - Is now the right time to watch a film about trying to life under the gaze of a dystopic government with a crippling and heartless bureaucracy on the eve of what could be the downfall of representative democracy in this country?

QFS No. 158 - The invitation for November 27, 2024

Brazil is directed by Terry Gilliam, the mad-genius behind (and part of) Monty Python’s Flying Circus, the still-quotable Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), Time Bandits (1981), Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), The Fisher King (1991) in which Mercedes Ruehl* won an Oscar, the terrific 12 Monkeys (1995) and other films that are all a little ... askew. What a fascinating career Gilliam has had as a comedian, animator, actor and filmmaker. This is our first of his movies we’ve selected for Quarantine Film Society.

And this one is a favorite of mine – darkly funny, unpredictable and visually captivating, stunningly so at times. I first saw Brazil after someone recommended it to me while a student (…fellow…) at the American Film Institute and the movie stuck with me immediately. The story of how Brazil was made and released has become something of a dark tale itself. There are three versions of the movie that exist in the world – the original European release that’s 142-minutes long, the American version that’s 132-minutes long (probably the one you’ll find out there on streaming), and the so-called Sheinberg edit also known as the “Love Conquers All” version that’s only 90-minutes long. I’ve seen some aspects of each of these, and whatever you do, do not watch the Love Conquers All version because it’s an abomination.

Is now the right time to watch a film about trying to live under the gaze of a dystopic government with a crippling and heartless bureaucracy on the eve of what could be the downfall of representative democracy in this country? Sure why not. Good to know what’s in store for us! Eh.

Anyway, join watch and and discuss below!

*Not only was she later to be directed by yours truly in an episode of television, she also has the distinction of her first and last name sounding like a complete declarative sentence.

Reactions and Analyses:

There’s a sequence in Brazil (1985) that captures so much of what the film attempts to say about society, progress, perception versus reality and also captures director Terry Gilliam’s unique vision, all in one 20-second (or less) moment and series of shots.

Sam (Jonathan Pryce) is driving in his ludicrously tiny car, dwarfed by the wheels of a huge construction vehicle driving next to it. Then, the shot cuts from Sam’s face to what we presume is a POV shot of him driving through the city which we haven’t yet seen. This sort of cut is a conventional type of edit where we as the audience sees what he’s seeing.

It’s a driving point-of-view through a sleek, futuristic world with what appear to be cooling towers above uniform, efficient-looking buildings. But then, as the shot keeps moving (again, as though we are in the car looking out the domed windows as Sam is doing), suddenly a giant head of a disheveled-looking man holding a beer bottle appears above the buildings.

The moment is long enough to give us a sense of what is going on? Is this some sort of giant? But then it cuts to a wide shot of the actual city – this was just a model in a glass case of what the city was proposed to look like, with this drunken fellow now peering into it and Sam’s car driving past the model in the background through what the city actually turned out to be.

This sequence is illustrative of Gilliam’s work generally and themes of Brazil specifically in the following ways. First, it toys with filmic convention – we have an expectation of what we should be seeing (a POV) but the gag is a misdirect, played for laughs. But it’s also a commentary. People (government or businesses) promising one thing but the reality ends up being something totally different – both the shot and the subject in the shot (the cityscape). The wide shot shows the same towers as the model, but run down, graffiti covered. It’s no mistake that these buildings are named “Shangri-La Towers,” an elevated name for a dilapidated place.

Hidden in this is a third aspect: who is to blame for these promises not being kept? And are we simply powerless to hold anyone accountable?

We are victims of indifference to our circumstances in an uncaring world, Brazil tells us. Bureaucracy (paperwork!) is dehumanizing – no one takes responsibility because in a world where authority is both decentralized and opaque, there’s no one person to blame. Everyone is at fault therefore no one is. As perfectly described in this exchange:

Sam Lowry: I only know you got the wrong man.

Jack Lint: Information Transit got the wrong man. I got the right man. The wrong one was delivered to me as the right man, I accepted him on good faith as the right man. Was I wrong?

That wrong man was poor Archibald Buttle (Brian Miller) who later died after being taken away in a case of mistaken identity – in that, they have the wrong name entirely and are looking for Archibald “Harry” Tuttle (Robert DeNiro). Jill Leighton (Kim Greist) attempts to find out what happened to her neighbor Mr. Buttle but since he’s considered a criminal, she’s only met with institutional indifference, given the ol’ run-around.

Sam, however, is in the system. So surely he can fight it – that’s where we think the film is going. Someone who is of the system but doesn’t really care for it will use his knowledge of the system against it to take it down and make the world a better place.

Gilliam, however, isn’t one for the Hollywood convention of a happy ending (as is thoroughly documented in his fight with Universal Studios and Sid Sheinberg to get Brazil released back in 1985). Instead, Sam, who has apparent privilege as a worker drone in the Ministry of Information and as the son of a prominent member of the government, in the end can’t defeat the system nor can he prevent himself from being a victim of it either.

One of our QFS group members brought up this phrase that I’ll try to remember when talking about Brazil in the future – it’s Kafka meets Capra. Comparisons to George Orwell and his 1984 are of course impossible to miss, but it’s not entirely accurate. The seminal book paints a bleak and ultimately joyless world living under a totalitarian state. Brazil’s world isn’t quite as bleak – in fact, the rich among them are very happy. They can endure routine terrorist attacks as “poor sportsmanship” and can continue to eat brunch so long as a barrier blocks them off from the horrors unfolding behind them. Or they can completely change their appearance with the right cosmetic surgeon. And Sam’s inner mind is full of fantasy and light - he’s actually fighting the system in his dreams, as opposed to being swallowed by it in reality.

Although the less wealthy and poor are victims of an uncaring world – the Buttles, for instance – Gilliam plays all of this for absurdist laughs as opposed to bleak sadness. The film is satire, not a post-apocalyptic look back at a world lost as we inhabit a brave new world. Gilliam has said that Brazil does not take place in the future and even the title card says “somewhere in the 20th Century” (which now of course puts this film firmly in the past). So it’s about our present day where consumerism is most important, a world where a child asks Santa for a credit card, a procession marches by with people holding up “Consumers for Christ” banners, and the guard implores Sam to confess quickly otherwise his credit score will suffer. Twentieth century “satire” here comes dangerously close to full on 21st Century reality.

And, I dare say, the film does find a way to have something resembling hope. Well maybe not as far as hope, but one can interpret that, in the end, Sam has found a place unreachable by the overbearing State – his innermost mind. The ending – the very ending, not what appears to be ending with Sam being rescued by the very terrorists he’s accused of being a part of – but the final moment of Sam in the chair humming the tune that’s the film’s namesake. He has gone off into the sunset with a woman he loves, free from paperwork and the dirty city.

Or, maybe they’ve already performed the lobotomy and it’s as bleak as saying – whatever you do, the State wins in the end (as does Big Brother in Orwell’s work). It’s unclear here in Brazil, but what’s clear is that the filmmaker shows a man in a chair surrounded by darkness, only to have that darkness dissolve into clouds and the world of his dreams. To me and to several of us in the discussion group, that is a glimmer of something brighter from the outside world.

Much has been written about the groundbreaking production design and imagery in the film and what’s striking about seeing it now, in the 21st Century, is that this film was made at all. In our current movie landscape, only a two or maybe three directors are able to create an entire world something as big, bold and maniacal as this – perhaps only Christopher Nolan, Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese and maybe Denis Villeneuve – without relying upon pre-existing source material. “I.P.” to use the language or our times. And Brazil is a lot for a first-time viewer, we discovered – it’s full of visual gags and stimulation, extraordinary camera work, clever dialogue with that Monty Python-esque British humor inflected throughout. You could watch the film all the way through just for the propaganda signs throughout (“Suspicion breeds confidence.”) And it’s just a utter stroke of genius that this whole thing is set off by a bug falling into the printing machine. A system so confident in its infallibility but yet the tiniest of creatures can cause it to fail.

Brazil is full of big ideas packed into a madhouse of a film. If there’s one thing we’re missing, one sadness at revisiting a work as innovative and inventive as Brazil, is that there are so few of its kind since then. So few original films on that scale that are about ideas. Perhaps Nolan is the only one making inventive big world creation films about ideas. There’s a bleak homogenization in our movies, one big action or comic-book based film looking almost exactly like the next. It’s our version of being surrounded by gray walls.

Are we living in Gilliam’s Brazil or some version of that now? I don’t think it’s as bleak as all that. After all, we’ve all but gotten rid of paperwork.

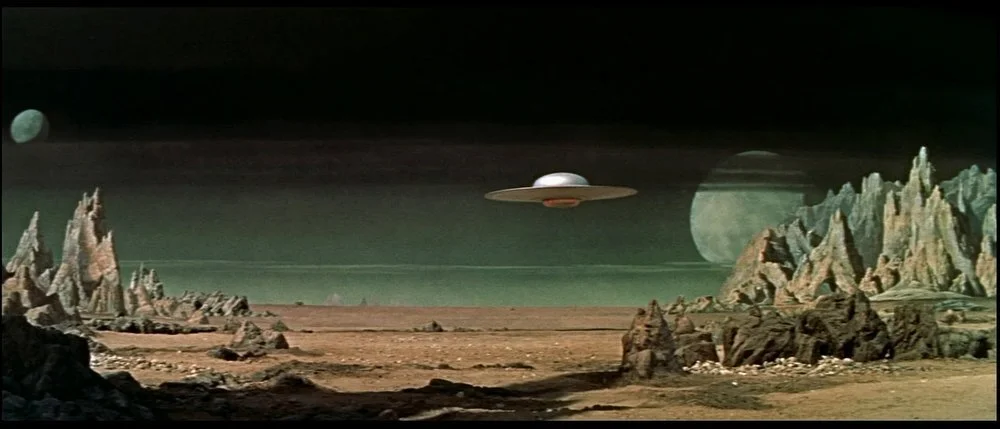

Forbidden Planet (1956)

QFS No. 119 - This is going to be an interesting one in that Forbidden Planet is (A) adapted from William Shakespeare and (B) we’ll be forced to take Leslie Nielsen seriously, he of Airplane! (1980) and the Naked Gun franchise fame.

QFS No. 119 - The invitation for August 9, 2023

This is going to be an interesting selection for us at Quarantine Film Society. Forbidden Planet is (A) adapted from William Shakespeare and (B) we’ll be forced to take Leslie Nielsen seriously, he of Airplane! (1980) and the Naked Gun franchise fame.

I’ve wanted to see this film for a little bit and I thought it’s time to return to pure escapist fare from an era before the special effects were super special but definitely inventive.

Join me in seeing Forbidden Planet and we’ll discuss!

Reactions and Analyses:

Watching Forbidden Planet with the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to see how influential it was to the next generation of filmmakers who expanded the possibilities of science fiction motion pictures. The entire film could be an episode of Star Trek, complete with the confident (and perhaps a touch pompous) captain and a mission by an Earth space agency in a time of great space exploration. As far as I can tell, this is the origin point of “hyperdrive” to propel a mission into space. Add a human-like docile Swiss-army-knife of a robot Robby and you get the serve as prototypes for hyperspeed, C-3PO and R2-D2 from the Star Wars universe all in Forbidden Planet.

The world created by Fred M. Wilcox in Forbidden Planet is vibrant and mysterious. He contrasts the drab greys and metallic colors of Commander Adams (Leslie Nielsen)’s crew with the pastels of the landscape and the lush tones of Dr. Morbius (Walter Pidgeon)’s home and interiors. Altaira (Anne Francis) prances in clothes that deliberately angelic and pure. The film, though science fiction, is a mystery set in a truly new world.

For all of the beauty in the world of Forbidden Planet – of which there is plenty – there lies at the center of the story a heady concept at its heart. Morbius was shipwrecked on this planet two decades earlier and is the only survivor, along with his daughter Altaira. In that time, they discovered remains of the Krell, a highly advanced species who became graceful geniuses and harnessed power in ways that dwarfs what humans have been able to do. Morbius, by using their machinery, has expanded his own mental power as well.

However, the Krell are gone. And the thing that killed them might be the very thing that wiped out Dr. Morbius’ fellow travelers two decades earlier – an unseen plague. That unseen plague steadily starts to eliminate members of Adams’ crew. So that’s the central mystery of the film. Who, or what, is the invisible monster on the island and can it be stopped?

At first, Morbius seems set up to be a mad genius villain. Yet, he’s perplexed by the monster on the island too. At first we’re led to believe it’s Morbius who is somehow responsible, that he’s cruelly eradicating all of his fellow Earthlings. And while it doesn’t lead us down that path too far, it does something surprising. The monster is Morbius. It’s his id – the part of his subconscious that is primal and instinctual, as described by Dr. Sigmond Freud. Fear, hunger, hate, shame – this creature is a manifestation of Morbius’ id.

And what brought about anger and fear from his id to create this creature? The visitors from Earth leering at his daughter. He fears her leaving, of becoming a woman, of choosing to go with Commander Adams and his crew and leaving him behind. And to be fair to Morbius, the men are very creepy. All of them are fawning over Altaira, with Adams going so far as saying that, well, what do you expect – you’re dressed like that and we’ve been trapped on a spaceship together for many months.

Ironically, it’s this aspect of the film that’s most dated and not the visual and special effects - it’s this obvious misogyny, tolerated or even accepted when the film. And moreover, she has never even seen a man who wasn’t her father, so how could she possibly know how to behave around them, even if Adams was right?

For their part, the visual and special effects hold up and are incredibly … effective … and at times spectacular. Perhaps except for Robby the Robot. Who everyone loves but definitely wouldn’t stand a chance against the likes of even the most simple of droids from the Star Wars Universe. (We mean no disrespect - Robby is a legend of filmand television.)

But the men do fall for Altaira and she for Commander Adams, hence justifying Morbius’ fears. As one QFSer put it in our discussion, it’s like a frat party just landed next to a house with a guy and his pretty daughter. Looking at it from this vantage point, I couldn’t help but feel like I understand Morbius – he’s acting out of primal need to protect his daughter from these creeps. So the film is heady and surprising in that way. There’s no traditional villain; Morbius is unaware of what he’s done to create the invisible creature from nightmares. However, the film doesn’t present Morbius in a sympathetic manner, focusing more on the hubris of a man who thinks he’s above it all since he unlocked higher intelligence. But all he’s done is push his baser instincts aside and created a monster.

This is quite difficult to follow and untangle at first since it’s all done in dialogue with one small twist: Robby is unable to shoot the creature. Because the creature is Morbius and Robby has been programmed never to harm a person. This is the one visual way Morbius - and the audience - finally understands that the creature is from Morbius’ psyche. Adams explains it all but it’s difficult to comprehend while the id monster is crushing doors and bearing down on them. In some ways, though, the scariest creature is one you can’t fully see - and this one, we only see once while it’s caught in the electric fence. That one time is terrifying enough and gets great mileage for the remainder of the film.

Despite some of these gaps and missteps, Forbidden Planet is incredibly enjoyable. Robby the robot is actually too great of a robot. Any robot who can both make a dress from scratch as if putting in A.I. prompts or can make 60 gallons of bourbon after “sampling” some of it (and burping), is a dream come true. He drives like race car driver and has gentlemanly manners to match. If anything, Altaira should be paired with Robby the Robot.

Ten years after Forbidden Planet Gene Roddenberry’s series Star Trek debuts on television, and eleven years later, Lucas makes Star Wars (1977). Going back to Forbidden Planet after seeing those two expansive successors feels like visiting an original text. Science Fiction has been around from before the invention of the motion picture. And once the motion picture was invented, science fiction became one of its primary genres. Yet, it’s easy to see how our two biggest tentpoles for Science Fiction began here, with Forbidden Planet, long ago on Altair IV in a galaxy far far away.