Witness for the Prosecution (1957)

QFS No. 169 - Billy Wilder, one of the American greats, now can add another posthumous feather in his cap – three-time QFS selectee. There can be no greater honor. We previously selected The Lost Weekend (1947, QFS No. 84) and Ace in the Hole (1951, QFS 136), and this week’s selection Witness for the Prosecution has been on my to-see list for a while now.

QFS No. 169 - The invitation for March 12, 2025

Billy Wilder, one of the American greats, now can add another posthumous feather in his cap – three-time QFS selectee. There can be no greater honor. We previously selected The Lost Weekend (1947, QFS No. 84) and Ace in the Hole (1951, QFS 136), and this week’s selection Witness for the Prosecution has been on my to-see list for a while now.

It’s a classic that’s been overlooked by me for far too long, and it gives us a chance to once again see Marlene Dietrich, who we briefly saw recently in Touch of Evil (1958, QFS No. 160) and will watch her at length in here. And also a treat to see the great Charles Laughton, all in Wilder’s capable hands. Very much looking forward to watching and discussing with you.

Watch Witness for the Prosecution and join us to discuss

Reactions and Analyses:

A somewhat standard question came up in our QFS discussion about Witness for the Prosecution (1957) that revealed a surprising result – had anyone seen this before? Only one person had, and that person is not a filmmaker and happens to be the only one in our group who is old enough to have seen it in the theater about the time it was released.

For a group of filmmakers who have a wide variety of cinema watching history from all parts of the world, many of whom went to some of the greatest film schools around – nobody had seen this Billy Wilder classic before. This would be understandable if this wasn’t a good film, lost in the dustbin of time.

But Witness for the Prosecution is quite the opposite. Wilder executes a nearly flawless whodunnit with his typical firm direction with a cast delivering stellar performances. So why is this film not remembered and revisited in the way Some Like it Hot (1959) or Double Indemnity (1944) or Sunset Boulevard (1950) or The Apartment (1960) or even Ace in the Hole (1951) or The Lost Weekend (1945) are? The film is not outdated, not in a way that would render it quaint or old-fashioned. In fact, in that same year there’s another courtroom drama that continues to be regarded as one of the great films that has withstood the test of time, and that’s Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men (1957, QFS No. 81).

Witness for the Prosecution is worthy of that stature as well, in many ways. Lumet’s film is a classic, real-time, single-room masterpiece so it’s understandable that it continues to be studied by film students and storytellers today, so it’s no wonder that legal drama has endured. Wilder’s film, adapted from an Agatha Christie play, is a masterclass in setups, payoffs, and twists.

Sir Wilfrid Robarts (Charles Laughton), infirm and told to no longer take complicated criminal cases, takes one he can’t resist – a man accused of murdering an older woman with whom he had become friendly. Leonard Vole (Tyrone Power), the accused, of course maintains his innocent and the case is thin with mostly circumstantial evidence pointing a finger at him. But why would he kill a woman who was giving him money and attention Robarts speculates, so the case seems pretty open and shut.

That is, until the newspaper shows up and it’s revealed that the murdered woman, Emily Jane French (Norma Varden) had changed her will to leave a huge amount of cash to Leonard. Well now the case is too much to resist and Sir Wilfrid must take it, despite the protestations of his nurse Miss Plimsoll (Elsa Lanchester). The police arrive at the law offices and take Leonard into custody.

Further complicating manners – and here is another great setup – is Leonard’s wife, the seemingly steely cold Christine (Marlene Dietrich). Christine, a German émigré, appears unphased by her husband’s arrested and accusation of murder, not wailing and sobbing as Sir Wilfrid said he expected. In fact, it’s not entirely clear whether Christine’s testimony on behalf of their defense will actually be useful in any way.

All of this is a perfect mystery setup and it’s no wonder that enough people over the years assumed this was an Afred Hitchcock film that they would go up to him and tell him how much they loved Witness for the Prosecution. You’ve got a money-based motive from a man who vociferously proclaims his innocence. Throw in a mysterious femme fatale. Toss in some question marks about crime timeline and the couple’s history. Add an ornery lawyer willing to step into the fray, and there it is – the making of enough compelling elements and twists to keep us guessing.

So we, the audience, are led to believe – with some uncertainty – that Leonard was in a “relationship” with Mrs. French, much to the disappointment of his wife Christine. And maybe Leonard was playing the long game to get at her money to fund his flimsy inventions. And it’s revealed that Mrs. French spotted Leonard with a younger woman visiting a travel agency. All of this is circumstantial, though, as Christine had provided an alibi that Leonard had come home that evening of the murder.

The case seems on track with some wobbly uncertainty but Leonard hasn’t been pinned down with any hard evidence. But then a bomb is thrown into the case. Christine is called as a witness for the prosecution, not the defense. Sir Wilfrid voices his objection because a wife cannot be legally compelled testify against a husband.

But wait! She is not his wife! Not legally. She was still married to her German husband and had misled Leonard. Or so we think! On the stand, she says that Leonard did it, that he came home with blood on his sleeve and confessed to her. Threatened with perjury, she stands by her story and says she used Leonard to come to England and leave post-war Germany behind. The testimony is devastating and crushes both Leonard and Sir Wilfrid’s case.

But wait! A mysterious Cockney woman summons Sir Wilfrid to a bar and provides letters that say this mysterious woman’s husband Max and Christine were having an affair and they intended to frame Leonard in order to send him away to prison so Christine and Max can be together. The letters, proven to be authentic in court, provides enough evidence for Sir Wilfrid to sway the jury to acquit Leonard.

But wait! After the verdict, Christine reveals that she was the mysterious woman in a fake Cockney accent and stage makeup with the letters that were … fake! It was all a ploy because she really did love Leonard and though it’s true he murdered Mrs. French for the money, he can’t be tried again. Leonard, free, comes and embraces Christine for her perfect execution of the plan. Sir Wilfrid is actually bested.

But wait! A young woman, seen earlier as an audience member next to Miss Plimsoll, turns out to be indeed the woman at the travel agency with Leonard and they did indeed intend to take Mrs. French’s inheritance and sail away somewhere. This twist is incredible – it even shocks Christine who went through all the trouble to save Leonard from the gallows. And Leonard is matter-of-fact and transactional about it – you used me to leave Germany, so what’s the difference if I use you? Even Steven, as they say.

But wait! Christine, devastated, grabs the murder weapon, still (oddly) on the evidence table, and plunges it into Leonard, killing him in the court. As Christine is taken away, Sir Wilfrid says – cancel my trip to Bermuda, I’m taking this case.

All of this in a tight less-than-two-hours runtime. And this is Wilder’s genius and perhaps also why he may not always get his due on the all-time greats – his directing does not draw attention to itself. His characters are terrific, his performances are legendary, and his camera work is subtle and usually enough to tell the story with the frame. His side characters here are terrific, as they are in Some Like it Hot for example – the suspicious Scottish maid Janet MacKenzie (Una O’Connor, reprising her role in the original stage production), is a scene stealer, for one. And the exquisite married-couple bickering between Sir Wilfred and Miss Plimsoll is even more delightful once you discover that Laughton and Lanchester were an actual married couple – a wink to the contemporary audience who would’ve enjoyed seeing the two on screen as “adversaries.”

Although it might not be remembered as immediately as other films of the era, several of us in the QFS group quickly found a modern comparison in Primal Fear (1996) in which Edward Norton’s character in the end reveals he was actually the guilty “Roy” the whole time, not the innocent “Aaron,” which leaves Vail (Richard Gere) alone, stunned, and defeated.

Wilder in Witness for the Prosecution could have ended the film that way, with Sir Wilfrid losing in the end. This would’ve aligned with his bleak ending of Ace in the Hole. But instead, the story concludes with Wilfrid not giving up, not retiring, and taking on a case that’s seemingly a lost cause. (Which got us wondering – does that case seem winnable? Answer: argue Christine suffered from temporary insanity.)

Witness for the Prosecution may also have suffered from the advent of television. This type of story, though still told on the big screen, becomes a staple of procedural episodic TV – everything from Law & Order to Criminal Minds to Perry Mason – for the next half century. Is that the reason people tend to forget or not revere Witness for the Prosecution?

Whatever the reason may be, it’s clear that Wilder’s unassuming style was ideal of a seemingly simple film with complexity lurking beneath. It’s also clear that Witness for the Prosecution should be remembered and studied for its writing, characterizations, and the simplicity with which Wilder tells a story on screen.

Ace in the Hole (1951)

QFS No. 136 - I’ve managed to see a great deal of Wilder’s films but he made so many that there are a lot left for me to watch. He’s another one, like John Ford, with a very high batting percentage of great hits. I went with Ace in the Hole because, well, don’t we all want to bask in the glow of Kirk Douglas’ chin for nearly two hours?

QFS No. 136 - The invitation for March 27, 2024

This is our second Quarantine Film Society selection by the great Billy Wilder, after having seen one of his earlier films The Lost Weekend (1947, QFS No. 84) a couple years ago. Ace in the Hole (1951) has been on my to-see list for some time, so I’m very much looking forward to it.

I was tempted to select a Wilder film I’ve already seen because they are so rewatchable. And I’ve managed to see a great deal of Wilder’s films - Some Like it Hot (1959), Sunset Boulevard (1950), The Apartment (1960), Double Indemnity (1944) are such terrific classics - but he made so many that there are a lot left for me to watch. He’s another one, like John Ford, with a very high batting percentage of great hits. I went with Ace in the Hole because, well, don’t we all want to bask in the glow of Kirk Douglas’ chin for nearly two hours?

Reactions and Analyses:

One of the most surprising aspects of Ace in the Hole (1951) is that it’s from 1951 and not 1971. There’s an expectation for many of the post-World War II American films, that they have a Capra-esque quality. A happy ending or at least one that’s, at best, ambiguous or a qualified victory for the protagonist.

A happy ending Ace in the Hole certainly does not have. One of our group members highlighted a shot at the end of the movie, where the crowds have recently left and all that remains is Leo’s father near a sign that reads “Proceeds go to Leo Minosa Rescue Fund.”

It’s a shot that speaks to the fickle nature of the crowd, the spectacle over, and all that remains is the detritus of the carnival and a family in ruin. Leo (Richard Benedict) has died. His wife Lorraine (Jan Sterling) has departed with the masses, just as she intended to early on before Tatum (Kirk Douglas) convinces her that her fortunes will change soon. And Tatum, having used Leo and keeping him trapped longer than necessary in order for him to reap the benefits of the sensational story going viral before “going viral” was a term, also dies. But not before a final act of almost valor.

The 1970s – coming on the heels of New Wave moments throughout Europe which in turn came on the heels of Post WWII neorealism – featured a generation of filmmakers who were raised by people who had witnessed the horrors of humanity and understood that real life had no clean happy endings. Obviously, this is an overgeneralization but the trends are clear to see from the films that came to life in this era in the second half of the 20th Century.

With its social commentary on human nature and their attraction to spectacle, the media’s role in fanning the flames of that human nature, and a non-Hollywood ending Ace in the Hole feels like an independent film from the 1970s and not a studio release from twenty years earlier. You can easily see a throughline between this and Network (1976), a film whose very essence is an analysis of media, entertainment and sensationalism. The cynicism in Ace in the Hole feels uncommon for the 1950s, with the Cold War in its infancy and the Allies victory in World War II fresh in people’s minds. The fact that it’s Billy Wilder and that the film is twenty years before its time, in some respect, is perhaps why I’m so drawn to it now and why it has been rediscovered as an overlooked classic of the time.

Tatum says early in the film, “You pick up the paper, you read about 84 men or 284, or a million men, like in a Chinese famine. You read it, but it doesn't say with you. One man's different, you want to know all about him. That's human interest.” Tatum, as an anti-hero, displays a deep understanding of that human nature throughout Ace in the Hole. Sheriff Kretzer (Ray Teal) hates him but Tatum turns him around and knows what the sheriff most wants – to be seen as powerful and important. Tatum tells Sherrif Kretzer how he will promote the sheriff as the man most determined to save Leo and in exchange Tatum gets exclusive access to the mine and the metaphoric gold inside. He convinces Lorraine to stay in town and play the grieving wife because it will make her a star and make all of them money. Tatum is a devious genius and he almost pulls it off.

“Almost” is the operative word. His gamble has proven too costly and Leo dies. And here’s one of our primary debates happened in our QFS discussion group. In the end, does Tatum feel guilty? Is that what drives him at the end? He’s clearly devastated by Leo’s death – but is it because it ruins his own chance at stardom and the heights of journalistic fame? Or is it because he’s come to terms with the fact that he’s Leo’s “murderer,” that he directly caused Leo’s death and consequently has a moment of clarity?

Several in the group believed that Tatum has no real remorse. Sure, he didn’t want Leo to die but he also knew that it meant the end of his own life. Others believed that he did in fact feel remorse and you can see it by his solitary act of bringing in the priest to comfort Leo for his final moments. Then, Tatum literally shouts from the mountaintop to tell everyone that Leo is dead and the carnival should go home. If he was truly in for all of this glory himself, he would’ve let Leo die quietly and had the “scoop” on Leo’s final minutes. (“Scoop” in quotes because Leo is the one creating this scoop.)

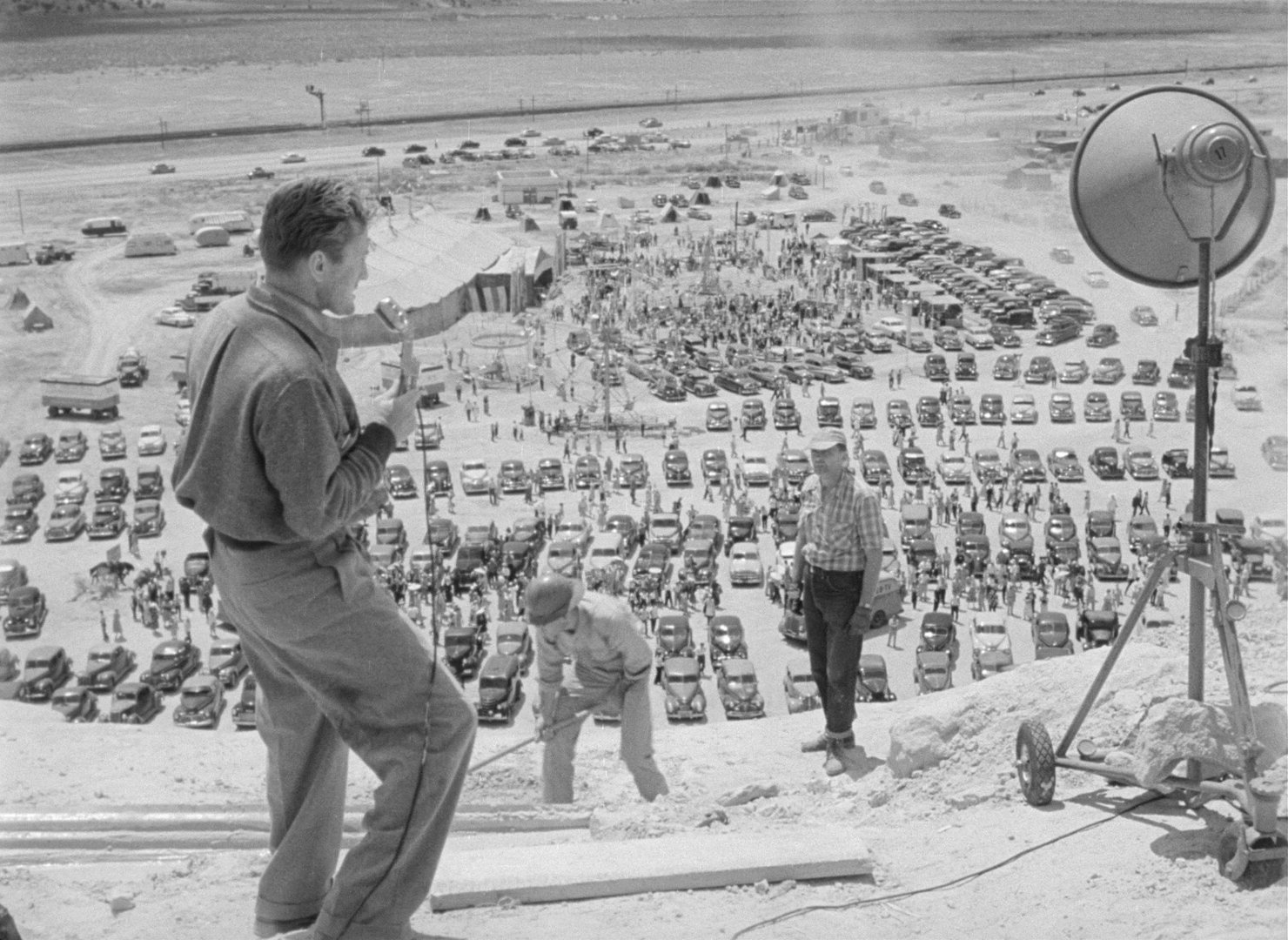

(Above sequence:) Tatum shouts from hilltop that Leo is dead. Is this the guilt-ridden face of a man full of remorse?

For me, personally, I think he did feel a measure of remorse and guilt but too little too late. And perhaps that’s why he doesn’t seek medical attention after Lorraine stabs him – he knows it’s his penance. He has to now suffer as he’s caused Leo’s suffering for his own gain. Perhaps explains why he accepts this pain without seeking amelioration or offering complaint, but it’s left (deliberately?) ambiguous.

People in our group brought up the cynicism but for me – and I said this early in our discussion – the film didn’t strike me that it was overtly cynical. And that probably says more about me or the time in which I live in now. For the 1950s, sure, the film is more cynical about human nature than popular culture portrayed. But we’ve now lived 75 years or so since then and seen the world revolve around capitalism, social media, hype, and the classically American propensity of squeezing money from every corner of human life. GoFundMe campaigns and “tribute” songs to raise money are the a logical extension of the funds to save Leo in the cave, the altruistic flipside of tragic spectacle.

And Leo – even the most “sympathetic” character in the film – is a grave robber of Native American artifacts! The person we’re cheering for to survive has, himself, stated that he’s probably cursed by the old spirits for robbing one too many times the burial sites of the indigenous of New Mexico. (Not to mention the studio so disliked the film that after its initial release they pulled it and remaned it “The Big Carnival” because people, you see, like carnivals so they might think it’s a fun movie! Talk about cynicism.) So it’s fair to say Ace in the Hole does have loads of cynicism – on screen and off – even though that’s not what first struck me.

The story is rife with plot holes as pointed out by the group, including the biggest one – why couldn’t Lorraine go down there to talk to Leo? It’s true – once Tatum goes down there frequently and it’s seemingly now safe to talk to Leo, then why can’t people who love him do that, like his parents? Also, is it believable that Tatum would suffer a stomach wound like that for so long? Only if he believes it’s a moral punishment.

And there’s this question – did Tatum ultimately win? He, too, is stuck in a hole – both he and Leo are in a hole together, one actual and one metaphoric. Both are counting on the other to extract them from their personal holes, but both die together. Tatum’s goal was to get back on top, become famous and return to New York. And while he doesn’t make it to New York and out of Albuquerque physically, he has become famous – people are cheering for him, the radio broadcast wants his exclusive thoughts. He is, for a moment, atop the world.

But it’s all fleeting, like the masses who come overnight and leave the next day as the tragedy ends. Ultimately, Tatum will become infamous and perhaps that’s victory enough – especially if you’re a cynic.