Witness for the Prosecution (1957)

QFS No. 169 - Billy Wilder, one of the American greats, now can add another posthumous feather in his cap – three-time QFS selectee. There can be no greater honor. We previously selected The Lost Weekend (1947, QFS No. 84) and Ace in the Hole (1951, QFS 136), and this week’s selection Witness for the Prosecution has been on my to-see list for a while now.

QFS No. 169 - The invitation for March 12, 2025

Billy Wilder, one of the American greats, now can add another posthumous feather in his cap – three-time QFS selectee. There can be no greater honor. We previously selected The Lost Weekend (1947, QFS No. 84) and Ace in the Hole (1951, QFS 136), and this week’s selection Witness for the Prosecution has been on my to-see list for a while now.

It’s a classic that’s been overlooked by me for far too long, and it gives us a chance to once again see Marlene Dietrich, who we briefly saw recently in Touch of Evil (1958, QFS No. 160) and will watch her at length in here. And also a treat to see the great Charles Laughton, all in Wilder’s capable hands. Very much looking forward to watching and discussing with you.

Watch Witness for the Prosecution and join us to discuss

Reactions and Analyses:

A somewhat standard question came up in our QFS discussion about Witness for the Prosecution (1957) that revealed a surprising result – had anyone seen this before? Only one person had, and that person is not a filmmaker and happens to be the only one in our group who is old enough to have seen it in the theater about the time it was released.

For a group of filmmakers who have a wide variety of cinema watching history from all parts of the world, many of whom went to some of the greatest film schools around – nobody had seen this Billy Wilder classic before. This would be understandable if this wasn’t a good film, lost in the dustbin of time.

But Witness for the Prosecution is quite the opposite. Wilder executes a nearly flawless whodunnit with his typical firm direction with a cast delivering stellar performances. So why is this film not remembered and revisited in the way Some Like it Hot (1959) or Double Indemnity (1944) or Sunset Boulevard (1950) or The Apartment (1960) or even Ace in the Hole (1951) or The Lost Weekend (1945) are? The film is not outdated, not in a way that would render it quaint or old-fashioned. In fact, in that same year there’s another courtroom drama that continues to be regarded as one of the great films that has withstood the test of time, and that’s Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men (1957, QFS No. 81).

Witness for the Prosecution is worthy of that stature as well, in many ways. Lumet’s film is a classic, real-time, single-room masterpiece so it’s understandable that it continues to be studied by film students and storytellers today, so it’s no wonder that legal drama has endured. Wilder’s film, adapted from an Agatha Christie play, is a masterclass in setups, payoffs, and twists.

Sir Wilfrid Robarts (Charles Laughton), infirm and told to no longer take complicated criminal cases, takes one he can’t resist – a man accused of murdering an older woman with whom he had become friendly. Leonard Vole (Tyrone Power), the accused, of course maintains his innocent and the case is thin with mostly circumstantial evidence pointing a finger at him. But why would he kill a woman who was giving him money and attention Robarts speculates, so the case seems pretty open and shut.

That is, until the newspaper shows up and it’s revealed that the murdered woman, Emily Jane French (Norma Varden) had changed her will to leave a huge amount of cash to Leonard. Well now the case is too much to resist and Sir Wilfrid must take it, despite the protestations of his nurse Miss Plimsoll (Elsa Lanchester). The police arrive at the law offices and take Leonard into custody.

Further complicating manners – and here is another great setup – is Leonard’s wife, the seemingly steely cold Christine (Marlene Dietrich). Christine, a German émigré, appears unphased by her husband’s arrested and accusation of murder, not wailing and sobbing as Sir Wilfrid said he expected. In fact, it’s not entirely clear whether Christine’s testimony on behalf of their defense will actually be useful in any way.

All of this is a perfect mystery setup and it’s no wonder that enough people over the years assumed this was an Afred Hitchcock film that they would go up to him and tell him how much they loved Witness for the Prosecution. You’ve got a money-based motive from a man who vociferously proclaims his innocence. Throw in a mysterious femme fatale. Toss in some question marks about crime timeline and the couple’s history. Add an ornery lawyer willing to step into the fray, and there it is – the making of enough compelling elements and twists to keep us guessing.

So we, the audience, are led to believe – with some uncertainty – that Leonard was in a “relationship” with Mrs. French, much to the disappointment of his wife Christine. And maybe Leonard was playing the long game to get at her money to fund his flimsy inventions. And it’s revealed that Mrs. French spotted Leonard with a younger woman visiting a travel agency. All of this is circumstantial, though, as Christine had provided an alibi that Leonard had come home that evening of the murder.

The case seems on track with some wobbly uncertainty but Leonard hasn’t been pinned down with any hard evidence. But then a bomb is thrown into the case. Christine is called as a witness for the prosecution, not the defense. Sir Wilfrid voices his objection because a wife cannot be legally compelled testify against a husband.

But wait! She is not his wife! Not legally. She was still married to her German husband and had misled Leonard. Or so we think! On the stand, she says that Leonard did it, that he came home with blood on his sleeve and confessed to her. Threatened with perjury, she stands by her story and says she used Leonard to come to England and leave post-war Germany behind. The testimony is devastating and crushes both Leonard and Sir Wilfrid’s case.

But wait! A mysterious Cockney woman summons Sir Wilfrid to a bar and provides letters that say this mysterious woman’s husband Max and Christine were having an affair and they intended to frame Leonard in order to send him away to prison so Christine and Max can be together. The letters, proven to be authentic in court, provides enough evidence for Sir Wilfrid to sway the jury to acquit Leonard.

But wait! After the verdict, Christine reveals that she was the mysterious woman in a fake Cockney accent and stage makeup with the letters that were … fake! It was all a ploy because she really did love Leonard and though it’s true he murdered Mrs. French for the money, he can’t be tried again. Leonard, free, comes and embraces Christine for her perfect execution of the plan. Sir Wilfrid is actually bested.

But wait! A young woman, seen earlier as an audience member next to Miss Plimsoll, turns out to be indeed the woman at the travel agency with Leonard and they did indeed intend to take Mrs. French’s inheritance and sail away somewhere. This twist is incredible – it even shocks Christine who went through all the trouble to save Leonard from the gallows. And Leonard is matter-of-fact and transactional about it – you used me to leave Germany, so what’s the difference if I use you? Even Steven, as they say.

But wait! Christine, devastated, grabs the murder weapon, still (oddly) on the evidence table, and plunges it into Leonard, killing him in the court. As Christine is taken away, Sir Wilfrid says – cancel my trip to Bermuda, I’m taking this case.

All of this in a tight less-than-two-hours runtime. And this is Wilder’s genius and perhaps also why he may not always get his due on the all-time greats – his directing does not draw attention to itself. His characters are terrific, his performances are legendary, and his camera work is subtle and usually enough to tell the story with the frame. His side characters here are terrific, as they are in Some Like it Hot for example – the suspicious Scottish maid Janet MacKenzie (Una O’Connor, reprising her role in the original stage production), is a scene stealer, for one. And the exquisite married-couple bickering between Sir Wilfred and Miss Plimsoll is even more delightful once you discover that Laughton and Lanchester were an actual married couple – a wink to the contemporary audience who would’ve enjoyed seeing the two on screen as “adversaries.”

Although it might not be remembered as immediately as other films of the era, several of us in the QFS group quickly found a modern comparison in Primal Fear (1996) in which Edward Norton’s character in the end reveals he was actually the guilty “Roy” the whole time, not the innocent “Aaron,” which leaves Vail (Richard Gere) alone, stunned, and defeated.

Wilder in Witness for the Prosecution could have ended the film that way, with Sir Wilfrid losing in the end. This would’ve aligned with his bleak ending of Ace in the Hole. But instead, the story concludes with Wilfrid not giving up, not retiring, and taking on a case that’s seemingly a lost cause. (Which got us wondering – does that case seem winnable? Answer: argue Christine suffered from temporary insanity.)

Witness for the Prosecution may also have suffered from the advent of television. This type of story, though still told on the big screen, becomes a staple of procedural episodic TV – everything from Law & Order to Criminal Minds to Perry Mason – for the next half century. Is that the reason people tend to forget or not revere Witness for the Prosecution?

Whatever the reason may be, it’s clear that Wilder’s unassuming style was ideal of a seemingly simple film with complexity lurking beneath. It’s also clear that Witness for the Prosecution should be remembered and studied for its writing, characterizations, and the simplicity with which Wilder tells a story on screen.

Touch of Evil (1958)

QFS No. 160 - Let’s get this out of the way first – in Touch of Evil Charleton Heston plays a Mexican. (But… barely.) Do with that information what you will. Just about the only negative I have about this film. Everything else in Orson Welles’ masterpiece places it high on my list of personal favorites.

QFS No. 160 - The invitation for December 11, 2024

Let’s get this out of the way first – in Touch of Evil (1958) Charleton Heston plays a Mexican.* (But… barely.) Do with that information what you will. For me, this is just about the only negative I have about this film. Everything else in Orson Welles’ masterpiece places it high on my list of personal favorites.

This is our first Welles film since Chimes at Midnight (1965, QFS No. 36) which kicked off the beginning of 2021 for us. Now as we wind down 2024, we revisit the auteur in one of the finest examples of film noir you can find. The opening shot alone is worth the price of admission (rental), which is how I first encountered the movie. A professor in college showed us this shot in class, stating that it’s probably the first (and maybe only?) continuous tracking shot that spans two countries,** and I was immediately hooked. And the fact that it was made in 1958, before the advent of Steadicam and sophisticated Technocrane systems makes it even more stunning.

Touch of Evil is a masterclass in staging and directing. You can see aspects of the director’s visual style from Citizen Kane (1941) here throughout, but this time in a crime and police procedural in which two detectives from two countries have to work together. Welles’ staggering physical presence is also something to behold in Touch of Evil – especially if you have in mind a young Charles Foster Kane.

Join our discussion below!

*In the 1995 movie Get Shorty, John Travolta’s character tells Rene Russo that Touch of Evil is playing in the theater and asks if she wants to join him and go see “Charleton Heston play a Mexican.” Which I think might be the first time I had heard of Touch of Evil and, yes, that piqued my curiosity.

**Another border-crime-based film we selected, Sicario (2015, QFS No. 153), does have a continuous shot that spans two countries but with a drone so … that’s cheating, isn’t it?

Reactions and Analyses:

The border between the United States and Mexico is the central locale of Touch of Evil (1958), the explosion and murder having taken place on the US side but the explosives having come from the Mexico side. The border is a physical space, but it’s the metaphoric nature of the border, the blurring of that line, that concerns Orson Welles throughout the film.

There’s a sense early on in the film that it’s not entirely clear which side of the border we are in at first in a given scene, the Mexican side of the American side. I recall having this slight confusion when I first saw the film nearly 25 years ago, but in the years and several re-watches since, I concerned myself less with this physical place than others in our QFS discussion group watching Touch of Evil the first time. But it’s certainly the case that at times it’s not immediately obvious where we are – Mexico or the US. And maybe this is intentional?

Welles’ ambiguity or lack of clarity on which side of the border we’re on appears to be deliberate. The border is neither here nor there, a between space that’s trying to create an artificial separation between the two. A fascinating place to set a crime and a movie – the in-between. And what happens in these in-between places? Shades of gray, ambiguous morality. Ramon Miguel Vargas (Charleton Heston) says, “This isn't the real Mexico. You know that. All border towns bring out the worst in a country.”

And in this, as the story unfolds Welles indeed shows some unsavory behavior on both sides of that dividing line and the filmmaker flips our expectations in this borderland. The “good cop,” the one holding up American ideals of justice, due process, innocent until proven guilty – that’s Vargas, the Mexican officer, from a place that is often portrayed as lawless and dangerous. It’s Hank Quinlan (Welles) who’s the “bad cop,” who skirts the law, who does things his own way in a manner of the Old West.

At the heart of Touch of Evil lies a central tension we find at the heart of many movies and series that take place in the world of criminal justice today – two competing visions of “justice.” Vargas goes after criminals but does it “by the book.” Some version of this code: there are people who commit crime and evil out in the world, and we put them away without compromising ourselves and our ideals. Quinlan is something closer to there is evil in the world so let’s not mess around by letting the courts and the lawyers screw things up and let these evil-doers go free. To put it another way, to catch monsters you have to become a monster.

Depending on the show, your hero is either the cop who goes by the book or the one who doesn’t. Both approaches to criminal justice have been lionized, but I’m guessing the one who breaks the rules to ensure the “bad guys” get put behind bars is the one we’ve come to see as our hero - a law-breaking good-guy to be admired on the screen. In Touch of Evil, Welles makes it clear that Vargas is the protagonist and Quinlan, at best, the antihero.

But he’s not “evil” or even a villain. There’s a fleeting moment where a drunken Quinlan shares a little of the motivation behind his particular brand of justice. His wife was strangled to death and the memory haunts him, drives him to prevent anything like that happening to anyone else. Is this justification for causing the suffering and misery of others? Vargas doesn’t think so and ultimately convinces his sergeant Pete Menzies (Joseph Calleia) that while they may have put some guilty people away, they definitely planted evidence and abused their power.

By the end of the film, Quinlan’s misdeeds catch up with him, thanks to Vargas exposing his past and with Menzies. Perhaps the most unexpected turns of in the film is Menzies’ who starts as an apparent sycophant but later on reveals a surprising moral compass. It’s his sergeant’s “betrayal” to Quinlan, after all, that leads to his ultimate downfall and the death of both of them.

But in the end, after Quinlan is dying, we hear that the suspect Sanchez (Victor Millan) admitted to being guilty of killing his lover’s father, Rudy Linnekar a local construction magnate (Jeffrey Green) and his girlfriend. Whether this is a real confession or a coerced one, the fact is that someone has confessed to the crime. So was Quinlan right – should he have just planted the explosives on Sanchez and the case would’ve been wrapped up? Is he vindicated, is his way of doing things actually more effective and efficient? This is an unanswerable question for sure, but one thing is certain – the chain of events of the film would not have happened, Quinlan would be alive, Uncle Joe Grandi (Akim Tamiroff) would also be alive, and Susan (Janet Leigh) wouldn’t have been drugged had Vargas not known and exposed the truth.

These dynamics play out in a film we selected at Quarantine Film Society recently – Sicario (2015, QFS No. 153). Another film that plays with the lawless nature of border towns, Sicario blurs the line between right and wrong but isn’t leaving it ambiguous, the filmmakers clearly have an opinion. In their version, the conflict at the modern border is a war, and as such the rules of war apply, not the rules of justice, law and order. Those ideas are quaint, antiquated, and useless in a borderland conflict where that conflict is military, not a law enforcement issue.

Welles appears to differ. If anything, even though Quinlan is ultimately right, his methods lead to destruction and death – including his own. This appears to be an indictment of the lawless man doing whatever he can to get results. Sicario believes the opposite.

Story aside, Welles gives a masterclass in staging just as he did seventeen years earlier in Citizen Kane (1941). Here, he fills the frame with his detectives, shoots everyone a little low angled – especially himself, giving Quinlan a massive presence in the frame. He’s imposing, terrifying. And Vargas mostly is on his own in the frame, heroic, the only good cop in a crooked world. The filmmaking, the camerawork, the snappy dialogue. If people want an example of noir, Touch of Evil is it.

There’s one undercurrent, though, that Welles submerges in the story, and that’s of race. The one thing about a border story between the US and Mexico is that race, class, capitalism – all of these play a huge part in any modern tale taking place along that dividing line. Sanchez, if he is ultimately guilty, was driven to do it because his girlfriend Marcia Linnekar’s (Joanna Moore) white father wouldn’t approve of her being in a relationship with him, a Mexican. The father Rudy Linnekar is the one who was murdered - so for the white American detectives, this is a plain and clear motive and add the fact that he’s from Mexico … well, it’s all an open and shut case. Just let Quinlan handle the particulars.

Vargas has just married Susan, and her actions can be interpreted as either naïve (she goes off with a Grandi gang member after all) or perhaps she feels safe being the wife of a senior Mexican narcotics officer. She’s brash, strong-willed, throws a light blub out of the window in anger at people peeping in on her. She feels as if nothing will happen to her – because she’s a white American? Maybe. And Vargas, for his part, “doesn’t sound like a Mexican.” (Of course this is because Heston doesn’t use an accent at all really.) But the American cops’ implications are is clear – maybe he’s not like one of them and we need to work around him. Race and nationality comes up throughout the film – even Uncle Joe Grandi says he’s an American citizen, using it as a shield to say how good he is. Welles deploys this throughout – not so much that it’s overwhelming, but enough to be unavoidable.

Welles asks - in a dark world, who do you trust? A man willing to do anything to put evil-doers behind bars (even if they might be innocent)? Or a man who goes after the corrupt but is beholden to rules that may allow the corrupt to buy their way back to freedom? Or is it not as simple as all of that? The exploration of these ideas is what makes Touch of Evil endure beyond its pulpy noir, and its artistry is what cements it as a classic.

Imitation of Life (1959)

QFS No. 152 - Director Douglas Sirk’s name is synonymous with melodrama. As someone who studies film and works in entertainment, this is one of those givens you know about even if you don’t know his movies.

QFS No. 152 - The invitation for September 25, 2024

Director Douglas Sirk’s name is synonymous with melodrama. As someone who studies film and works in entertainment, this is one of those givens you know about even if you don’t know his movies. I first learned about Sirk when Todd Haynes’ Far From Heaven (2002) hit the theaters. When it came out, Haynes made it clear it was an homage to Douglas Sirk films, in the story, the time period, and the style of the filmmaking.

Sirk, a Danish-German filmmaker was one of the many artists forced to flee persecution from the Nazis in the 1930s, just as Fritz Lang and Billy Wilder had to in the same era. Sirk made several German films before leaving the country and even directed short films into the late 1970s long after retiring from Hollywood filmmaking. I’ve been eager to see one of the classic Sirk melodramas – All that Heaven Allows (1955), Written on the Wind (1956), and this week’s film Imitation of Life – for some time. And this one stars Lana Turner who has a fun connection to our QFS No. 150 screening of L.A. Confidential (1997).

So envelop yourself in lush color tones, sweeping music, and likely overwrought emotion for our next film, the Douglas Sirk classic Imitation of Life (1959).

Reactions and Analyses:

A girl struggling with her racial identity, trying to find acceptance and ashamed of her mother. Her mother trying to convince her that she has nothing to be ashamed of, that she is enough. Another mother striving to achieve in her profession and follow her ambitions in a competitive, ruthless industry – the cost is time with her daughter, who feels a sense of neglect when she’s older despite all the comforts the mother has provided.

These all sound like story elements for a film in 2024, and yet Imitation of Life (1959) takes on all of this. The word our QFS discussion group kept returning to was “modern.” For a film that’s 65-years old set in a very specific time, this was surprising to all of us given Douglas Sirk’s approach to filmmaking.

While the narratives within the film are modern, Imitation of Life wouldn’t be mistaken for modern in its style. The film isn’t a gritty realistic portrayal of American life in the 1950s nor does it feature Method performances that were on the rise at this time (this film is only a few years after On the Waterfront, 1954) that mirrors today’s style of acting. Instead, in Imitation of Life we quickly find the popping color of the costumes, sweeping orchestral music, theatrical lighting with brightness punctuating the darkness, Lora (Lana Turner) emerging from shadows at the exact right moment.

These are all hallmarks of melodrama, production elements intended to enhance the emotions of the scenes, to create something that’s just slightly more elevated than reality. Take just the opening sequence – it’s set on a beach in New York City. It’s clearly a stage, a clever rear projection or painted backdrop juxtaposed with the live foreground of a beach.

But we forgive this detachment from realism quickly. One member of our discussion pointed out that it’s this lack of adhering to pure realism which allows us to accept the melodrama, to allow us to be swept along with it because we don’t question as much as we would something that’s more realistic. If you’re taken up by it, you can easily forgive the somewhat flimsy setup of a woman who meets a stranger at the beach and invites her and her young child to stay the night and eventually move in. For some reason, this didn’t bother me but perhaps in a film that commits to a broader cinematic realism, I would’ve been lost right away.

This elevated reality is what serves musicals very well, and I thought immediately of Hindi cinema a.k.a. Bollywood. In Hindi films, we are keenly aware of the theatricality because, of course, people don’t break out into song in real life, strictly speaking. So the melodrama inherent in Bollywood is forgiven because the cinematic language sets up this deviation from reality.

I was also reminded of another country’s master filmmaker, Spain’s Pedro Almodovar. At QFS we watched his All About My Mother (1999, QFS No. 109) and what struck me then is that the film felt like a telenovela with its plot twists and turns. Almodovar’s mastery of balancing melodrama and realism is one of a kind and is perhaps the only filmmaker I know who’s been able to pull off authentic emotion with twisting and turning plots that defy reality.

Somewhere in the spectrum between Bollywood and Almodovar lies Douglas Sirk. More than half a century ago, Sirk uses melodrama in Imitation of Life to probe the problematic racial dynamics in his adopted country, the United States. Originally from Germany, the filmmaker fled Nazi persecution and made a career in the American movie industry. I’ve noticed that often it takes a foreign-born director to keenly see some of the divisions of America and render them into art on the screen. In college, I had a terrific course that explored America through the lens of foreign-born directors. Though Sirk wasn’t in the course, he very well could have been where he would’ve joined the ranks of Milos Forman (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 1975, QFS No. 75), fellow German émigré Fritz Lang (Fury, 1936, QFS No. 37), and Wim Wenders (Paris, Texas, 1984), among others.

One of the commonalities those directors displayed was a foreigner’s ability to both admire their new homeland and also criticize it, warts and all. Which is also a way of expressing love of their adopted country. In Imitation of Life, Sirk sees that a white person can flourish, reach their heights, seemingly on their own. But in the background, working in the kitchen unseen, is their black counterpart toiling away. Lora ascends to the top of her career while Annie (Juanita Moore) supports her faithfully.

But at what cost? Annie is unable to convince her daughter Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner) – a girl who can pass as white – that being black is nothing to be ashamed of. Perhaps the love and care she spent supporting Lora and her daughter Susie (Sandra Dee) is the cost for Annie. While Sarah Jane’s struggles are deep, existential, and wrenching, Susie’s amount to feeling as if her mother wasn’t around to spend time with her. Not to trivialize Susie’s angst, but Sirk feels like he’s making a sly commentary here. A black girl’s struggle in America is very deep and profound while a rich white girl can have the luxury of not worrying about her personal identity but instead can worry about the usual things children worry about.

What struck me throughout the film is that the characters don’t live in a time where they have language to address or understand race relations. Lora doesn’t offer meaningful support other than to suggest that things will get better. And Annie is unable to talk to her daughter about race in a nuanced or meaningful way. Of course, they are living in a time where divisions are very real between white and black families – the decision that struck down legal segregation, Brown v. The Board of Education, only happened five years before Imitation of Life was released – so it’s understandable that they don’t know how to talk about race in a constructive way. We’re still struggling with it now, but we have more language and tools. What I’m saying is: everyone in this movie would’ve benefitted from being in therapy.

For me, the entire film is worth it for this one particular payoff: the scene where Annie in essence says goodbye to Sarah Jane. Annie has discovered that Sarah Jane has moved across the country to Hollywood with a new name, working in a chorus line as an object of desire (or as lascivious a job as could be permitted to portray in 1959). Annie goes to her and is done fighting with her daughter, but instead only wants to hold her. As a final act of motherly love, she does what Sarah Jane asks – to leave her alone and pretend they aren’t related.

The hold each other and both cry in each other’s arms. The roommate enters and as Annie leaves, she tells the roommate she used to raise “Miss Linda” – Sarah Jane’s new name, tacitly acknowledging her daughter is someone else now. After Sarah Jane closes the door, she cries sans says she was raised by a “mammie” “all my life.”

It’s devastating, and I did my best to keep from crying as much as they did. Throughout the film, Annie attempts to relentlessly be a mother. And in the end, what’s the most motherly thing she could do? Set her daughter free and assure her she could come back any time and her mother would be there to love her.

The melodrama builds and crescendos to this and somehow, even though the film doesn’t adhere to strict realism in anyway, I felt like I knew these people, these characters. As an American-raised child immigrants, I too have felt in many ways the way Sarah Jane felt in the film. I didn’t want to be seen as different than the other kids at school and at times not want my parents around where my classmates could see them. Sarah Jane is mortified when her mother comes to school to bring her an umbrella, revealing to the others that she’s actually black. I can’t say that I had experiences exactly like that, but I completely understood the character’s struggle in those scenes in a deep way.

Douglas Sirk gives the heft of the narrative to this story of identity, of race, in a way that’s uniquely American, and puts the burden on Juanita Moore in a titanic performance as Annie. In a meta way, Annie, the black character, has the bigger character arc, the bigger struggle, than Lora, played by one of Hollywood’s biggest stars Lana Turner. But it’s Turner that gets top billing, gets the posters and the recognition and, of course, the money. This too is a commentary, though unintended, about America, about life, and about Hollywood. In that way, Imitation of Life penetrates on more layers than maybe it even intended.

Halfway through the film, Annie deeply knows Sarah Jane’s struggle and says to Lora, “How do you tell a child that she was born to be hurt?” To utter this in a mainstream film in 1959 is no small feat. The fact that it’s probably still relevant is the real tragedy of Imitation of Life. Yet another aspect of what a modern 21st Century film this 1959 melodrama truly is.

Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959)

QFS No. 147 - Kaagaz Ke Phool – which translates to “Paper Flowers” – is known as one of the great films from the Golden Age of Hindi Cinema.

QFS No. 147 - The invitation for July 17, 2024

Let’s complete another chapter in our on-going Introduction to Indian Cinema 101!

Guru Dutt is one of the unheralded filmmakers from India. “Unheralded” is in quotes because he’s quite ... heralded? ... in India. Though recognized as a great in his own country, he never achieved international acclaim in his lifetime the way that Satyajit Ray did, for example. For me, I was first introduced to Dutt’s work about twenty years ago when Time magazine’s legendary film critic Richard Schickel listed Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa (1957) as one of the 100 greatest films ever made. Pyaasa is a classic that’s moving and also has the unofficial Hindi film mandated musical numbers. But the musical numbers in Pyaasa are not superfluous – they serve the story, bringing poetry to life and enhancing the story. His follow-up Kaagaz Ke Phool – which translates to “Paper Flowers” – is known as one of the great films from the Golden Age of Hindi Cinema.

Now is a good time to recap our course materials for Introduction to Indian Cinema. Here are the films the QFS has selected (in chronological order):

1. Apur Sansar (World of Apu, 1959, QFS No. 16) – part of Ray’s “Apu Trilogy” and the origin point of Indian independent and art cinema.

2. Sholay (1975, QFS No. 62) – a glimpse of a big mainstream Indian movie during an era when such films were uninfluenced by global cinema. Also, our first viewing of Amitabh Bachchan, the most famous movie star in the world.

3. Dil Se.. (1998, QFS No. 32) – where we could see the influence of MTV’s arrival into South Asia, in which a movie produced standalone music numbers that felt separate from the main film. Also showcasing the ascension of Shah Rukh Khan as global heartthrob and second most famous movie star in the world.

4. 3 Idiots (2006, QFS No. 118) – closer to present-day Hindi filmmaking ripe with broad humor, earnestness, and adapted from a popular contemporary novel.

5. RRR (2022, QFS No. 86) – example of a regional language film (Telugu) that exploded into the world consciousness, showcasing modern filmmaking India style.

That’s not bad for a four-year, unstructured and barely planned course into the filmmaking of the largest movie producing country on earth!

You’ll notice in the above list that Apur Sansar and this week’s film are both from 1959. But they represent completely different branches of Indian cinema. Apur Sansar is from Bengal and not considered part of the national films of India (which we now call “Bollywood” but is really known as “Hindi Films” you may recall from our previous lessons). Ray’s Apu Trilogy was more popular abroad than in his own country, where he produced and directed from outside of the national movie industry. He is the first known filmmaker to make a successful film outside the traditional Indian movie studio. The independent scene in India remained very thin for the next 50 years, but the Apu Trilogy is where it begins.

Whereas Guru Dutt was already a Hindi film star known all over India by 1959. While Ray toiled as what we would now call an independent filmmaker, Dutt was a studio filmmaker. He operated within the Hindi film ecosystem, casting stars (including himself) but told deeply personal stories in between the songs and the dances. Kaagaz Ke Phool represents our QFS selection from the Golden Age of Hindi Cinema.

And while Dutt made commercially viable films, his personal life was marred by strife. Perhaps the melancholic storytelling he showcased on the screen came from his world at home. Tragically, he died before he turned 40 possibly from an accidental overdose or possibly, he committed suicide. This is his final film as a director (he acted in eight or so more after this) and though his life was short, he left behind an incredibly impressive body of work as a filmmaker. Dutt remains a revered artistic luminary in India and in film circles – both Pyaasa and Kaagaz Ke Phool appear on “Greatest” lists in India and internationally, including the latter once appearing on the BFI/Sight and Sound Greatest Films of All Time list in 2002. I believe India also issued a stamp in his honor as well.

So join us in watching Kaagaz Ke Phool – the first Indian film in Cinemascope! – and we’ll discuss in about two weeks.

Reactions and Analyses:

In Guru Dutt’s Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959), there are a few scenes that concern horses and take place at a horse racing track. For a movie set primarily in the world of the 1950s Hindi cinema industry and very little to do with horses, this feels superfluous. And, for the most part it is superfluous – it doesn’t have much to do with the main storyline. But it pays off in a way later on thematically.

Rocky (Johnny Walker), who owns and bets on horses, reveals late in the film that one of his prized horses had to be shot and killed because it broke its leg and couldn’t race any more. Not much good now, but the horse had made me millions before, Rocky says. So we had to shoot the horse, he reveals, almost as an afterthought.

At the same point in the film, the protagonist Suresh Sinha (played by Dutt himself), a director who was successful and made many hits for his studio, has hit rock bottom. Drinking, depression, and abject loneliness left him a shell of a man – unemployable and forgotten. Not much good now, but this director made them all millions before. Suresh is not being put out of his misery in the manner of a horse, but perhaps he should be?

The metaphor is clear, and it’s brutal. Fame is fleeting and also no matter what you’ve done before or how successful you once were, you end up dead and alone. Which is what happens to Suresh, who, in what is the most savage scene of the film, dies quietly on the soundstage in which he had once flourished. The morning crew comes and finds him dead in a director’s chair, but the producer doesn’t care. He just wants the body moved (“what, you’ve never seen a dead body before?” he shouts) because the show must go on. The camera rises up to the heavens in a wide shot as light pours into the stage from the outside as Suresh’s lifeless body, small in the frame, is carried off.

It’s an incredibly cynical portrayal (and likely accurate from Dutt’s experience) of a ruthless world, specifically the movie industry. The fact that this is in a 1959 Hindi film – a film industry very well known for cheery, elevated and escapist fare – makes it even more surprising. What’s less surprising, perhaps, is that audiences at the time weren’t too keen on seeing Kaagaz Ke Phool, a notorious flop, only to be rediscovered and cherished now. Perhaps that says more about the times we currently live in than the quality of the film itself.

And to that quality – Kaagaz Ke Phool is a stunning masterwork of directing. Someone in our QFS group pointed out that not only do the shot selections evoke Orson Welles – deep focus, wide frames, low angles utilizing Cinemascope lenses for the first time in India – but Guru Dutt himself looks a lot like a young Welles himself. Both were prodigy actor-directors, both fought inner demons. And while Welles lived with his for a long lifetime in which he fought to regain the fame and power he had when Citizen Kane (1941) reached its ascendancy, Dutt’s demons proved too much for him, and instead died before he was 40. Dutt left behind a legacy of classics and a the tragic feeling that we were deprived of more great and meaningful films to fortify the Indian film industry.

It's easy to find parallels between Suresh in Kaagaz Ke Phool to Dutt’s own life. But beyond that, the film is a masterclass in portraying loneliness. Dutt with VK Murthy – one of India’s legendary cinematographers – has Suresh move between shadows and silhouettes, throwing the focus on the background and trusting the audience with extracting meaning from his imagery and juxtaposition of characters in the frame.

Perhaps the most evocative scene comes about halfway through the film. Suresh has discovered and clearly has fallen in love with the luminous Shanthi (Waheeda Rehman), a non-actor who reluctantly becomes a star in his movies. He’s still technically married to Veena (Veena Kumari) but has fallen in love with Shanthi, and Shanthi, has definitely fallen for him. But they can never be together. To portray this visually, Dutt has music playing between the two characters on a darkened soundstage, featuring the now-legendary Mohammed Rafi song “Waqt Ne Kiya Haseen Sitam” which roughly means “What a beautiful injustice time has done (to us).” There are only shafts of light in an otherwise dark space with each going in and out of shadows and light. It begins with his wife Veena in the scene (possibly imagined), looking distraught as the camera pushes in to a close up, cut with a similar closeup of Suresh as well.

Next, in a wide profile angle, Veena and Suresh are on opposite sides of the frame, the light is shining down in a shaft between them. Then, ghost-like, their translucent “spirit” selves separate from their bodies and move towards each other. The spirits come together in the center of the frame, a special effect shot dispatched for emotional utility. Then, Veena walks into a shadow, but when the figure emerges - it’s now Shanthi, the lover he cannot be with, smiling at him as the music swells.

It’s beautiful, it’s magical realism, and it feels as a definitive example of this is the Golden Age of Hindi Cinema. What characterizes the Golden Age of Hindi Cinema? My admittedly scant knowledge is that the Golden Age is this: all the hallmarks of Hindi film as we know now – melodrama, plot contrivances, depths of extreme emotion, goofy comic relief, evocative musical numbers – but told with a level of cinematic artistry and a trust in the audience’s ability to make meaning from the visual language made by the filmmakers. In the decades to follow, it’s clear that many of those hallmarks continue but two aspects don’t as often – the artistry and trust in the audience.

Not to say that Hindi films today aren’t awash with art and color and life – they surely are. But where Dutt uses all the language of cinema through camera, movement, performance, blocking, light, shadow, and nuanced performance (relatively speaking), modern Indian filmmakers tend to rely on spectacle and over-wrought performance and emotion. This is, of course, broad and my own observation as an Indian American filmmaker born and raised outside of that country’s film industry. But to me, it’s clear why so many Indian film goers who are old enough to remember the Golden Age lament the state of modern Hindi cinema. It simply was better in its basic storytelling, if not the technology and craft. Also, note the musical numbers. They express emotion and flow into the story, as opposed to the standalone numbers that follow and become the standard as Indian cinema progresses in the 20th Century.

One thing that was surprising for all of us in the QFS discussion group was how “modern” Kaagaz Ke Phool felt – a movie about movies and movie makers. The opening shots, if you weren’t paying attention, could’ve been out of Welles or John Ford or Michael Curtiz, reminiscent of American cinema of the 1940s. The film, though indigenously India and about India’s own cinema industry, could’ve been very easily the Hollywood of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950) or All About Eve (1950). There’s a timeless elegance to it – and perhaps that, too, is a hallmark of Hindi cinema’s Golden Age.

Dutt suffered from depression and addiction, as is now well known and was perhaps known then, too. He attempted suicide at least twice before his actual death, in which he may have killed himself (or perhaps accidentally overdosed – it’s not known for sure). This internal melancholy may have led to the abundant and drawn-out final quarter of the film where we watch Suresh’s deep and inexorable decline. This underlying melancholy is a feature of what is considered his preeminent classic, Pyassa (1957) which came out before Kaagaz Ke Phool.

Towards the end of the movie, Suresh, now at true rock bottom – an alcoholic shell of himself – has been cast as an extra in a film where Shanthi is the star. When she realizes who he is, she desperately runs after him but can’t catch him, cut off by adoring fans – an echo of a scene with Suresh from the beginning of the film. The song that plays is “Ud Ja Ud Ja Pyaase Bhaware” and in it, the lyrics say “Fly, fly away thirsty bee. There is no nectar here, where paper flowers bloom in this garden.”

Perhaps Dutt is saying here, as one QFSer pointed out, that there is no glory here in this world where things appear beautiful, like paper flowers, but it’s all an illusion. Paper flowers and fame are not real, will not give you nectar. If you want true meaning, true love, true fulfillment, then you need to seek it somewhere else.

If that’s truly what the filmmaker intended, then this sequence, this final sequence in this master filmmaker’s final film, is a cry for help, placed in a beautifully downcast work of true art. Not all films from the Golden Age of Hindi Film have endured in this way, and perhaps it’s because Dutt placed his finger squarely on something universal, deep, tragic, and true.

The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

QFS No. 137 - For our four-year anniversary of QFS, we decided to select an epic by the great David Lean. Yes, it took us four years to get to a David Lean film, and for the most part it’s because I’ve seen most of the epic classic ones. Lawrence of Arabia (1962) remains one of my favorite films of all time and we could easily have selected it to commemorate our four years of watching and talking about movies. But instead, I picked what is my second favorite Lean film, The Bridge on the River Kwai.

QFS No. 137 - The invitation for April 24, 2024

Happy Fourth Anniversary!

For our four-year anniversary of the Quarantine Film Society, we decided to select an epic by the great David Lean. Yes, it took us four years to get to a David Lean film, and for the most part it’s because I’ve seen most of the epic classic ones. Lawrence of Arabia (1962) remains one of my favorite films of all time and we could easily have selected it to commemorate our four years of watching and talking about movies.

But instead, I picked what is my second favorite Lean film, The Bridge on the River Kwai. I’ve seen it in the theater once and probably half a dozen times in total. (I have somehow managed to watch Lawrence of Arabia about six times in the theater over the last 20 years in LA, a personal achievement of which I'm quite proud.)

One of the things I love about David Lean and why I love his filmmaking is that he makes the epic personal. He crafts giant films on huge tapestries during times of war or conflict – but they are, at their core, character dramas. Lawrence of Arabia is, among other things, an exploration of a man’s identity, of living in between two realities, all set against the World War I proxy conflicts between Turkey and the Arabian kingdoms. A Passage to India (1984) examines race, imperialistic hierarchy, and tolerance during the British Raj rule of India. Doctor Zhivago (1965) is set during the Russian Civil War and beyond but concerns itself mainly with the love story between the two protagonists.

Set during World War II in Burma, The Bridge on the River Kwai is a fascinating tale of duty, of an almost sacred commitment to a task. The film questions whether that task is moral or not. We will discuss this further when we chat about the film, but I’ve always be interested in what is known in Hindu philosophy as dharma – one’s sacred duty – and The Bridge on the River Kwai manages the best portrayal of the concept I’ve come across in Western cinema through Alec Guiness’ character. Again, here the film is not about the war. But war surrounds the story. The epic is backdrop for the personal.

Speaking of epic, just a brief reflection on pulling off a four-year run of Quarantine Film Society. Sure, “pulling off” wasn’t really all that much doing. Simply (a) repeated unemployment of yours truly, (b) stubbornness, (c) an eagerness to write mini-film essays nearly weekly and (d) have at hand a bunch of maniacs willing to watch a film and get on an online video phone to talk about it.

These four years I’ve watched more movies than perhaps any other four year stretch of my life except perhaps for college. I’ve greatly expanded my working knowledge of the craft of cinema, American film history of the 20th Century, and have gained a greater appreciation of film as an art form – in that it can be interpreted less like a sentence in a book and more like a painting in a gallery.

For all of this, I thank you. I hope to keep this up for as long as I can. Join me to discuss The Bridge on the River Kwai as kick off our next four years of world cinema domination.

Reactions and Analyses:

Who is the antagonist in The Bridge on the River Kwai? For a film that has a lot of traditional action elements, it is not an action film in the classic sense. Or a war film in the classic sense, for that matter.

This question, though, of who is the antagonist or “the bad guy” is an interesting one and was quickly brought up by one member of the group. He argues that it’s actually Colonel Nicholson (Alec Guinness). He’s a maniacal man hellbent on living up to his own moral code, to the point of collaborating with who is his enemy.

This is a fascinating take on the film and several QFS members felt similarly. Nicholson, is governed by a code and cannot waver from it. If anything, his counterpart Colonel Saito (Sessue Hayakawa), who runs a prison work camp, is downright reasonable by comparison. Nicholson nearly sacrifices not only himself but his officers on principle. He nearly completely and totally collaborates with the enemy, very nearly (inadvertently) foiling the covert mission by his own government.

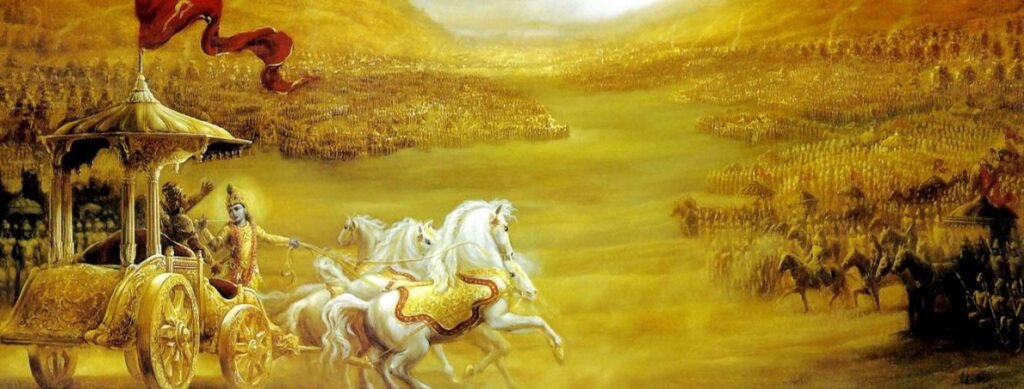

Consequently, several QFS members felt that this makes him a merciless sociopath. Sure, I can see that. But also, I’ve always seen him as totally and completely tied to his duty. As I wrote in the invitation to The Bridge on the River Kwai, for me Nicholson evokes the philosophical concept of dharma – which can be translated to spiritual duty, a duty that’s beyond mere obligation but something that’s deep inside of you that you have no choice but to fulfill. There are characters who appear in Hindu mythology who embody the concept, and at times they are unable to do anything other than their duty. They are, as I’ve heard referenced “bound to their dharma.” Rama from the epic The Ramayana has to obey his elders, his father, even when doing so triggers off a curse that leads to his father’s death. (There’s more to it than that but for simplicity’s sake, I’m boiling it down.)

Also, in the other Hindu epic The Mahabharata, the warrior prince Arjuna is on the eve of battle against his family and is paralyzed by inaction. Krishna, who is Lord Vishnu incarnate on earth, guides Arjuna through this crisis by reminding him that his duty is as a warrior for his people, and a warrior fights. Even when it’s going to be against cousins and uncles who he knows and loves – because he is on the side of righteousness. (Again, this is massively oversimplifying the Bhagavad Gita but go with me here.)

Now, I’ve always felt that Nicholson embodies this concept better than almost any character I’ve seen in a Western film that isn’t inspired by Eastern philosophy directly. And I still feel that way, but I noticed something different this time that should’ve been obvious to me before – this is an antiwar film. Nearly every war film is at its core an antiwar film. But The Bridge on the River Kwai is perhaps even darker. It’s not only addressing the cruelty of war, it criticizes the very necessity of war – and of the British Empire. The bridge is more than a bridge - it’s a symbol of colonialization and empire.

QFS members pointed out the arrogance of Nicholson, claiming their British engineers are superior intellectually to the Japanese ones, their workmanship and organization the model of the world. Some in our group couldn’t really tolerate that, which is totally valid. But this arrogance is entirely David Lean’s point. It’s this arrogance, this expressed superiority – that it’s all nonsense. And, in the end, futile and destructive. Like the British Empire, they’ve gone in with what they believe to be good intentions, but leave behind destruction, ruin, and death in their wake.

Or “Madness,” as the medic Major Clipton (James Donald) says in the last line of the film. And after the destruction, Lean leaves us with a final shot, an aerial pullback, wide, from the sky, with a jaunty British military tune. This is not accidental, and it’s an acerbic, biting final blow against the British. He could’ve chosen somber or desolate music. But the final tune has the flavor of cynical sarcasm to it.

And yet, it’s Nicholson, bound by dharma, who must build the bridge and can only do so the best he can. He can’t even comprehend what others are telling him when they say to not build it so well. There are many telling exchanges in the film, but this one to me stands out as emblematic of what I mean:

Major Clipton: The fact is, what we're doing could be construed as - forgive me, sir - collaboration with the enemy. Perhaps even as treasonable activity.

Colonel Nicholson: Are you alright, Clipton? We're prisoners of war, we haven't the right to refuse work.

Major Clipton: I understand that, sir. But... must we work so well? Must we build them a better bridge than they could have built for themselves?

Colonel Nicholson: If you had to operate on Saito, would you do your job or would you let him die? Would you prefer to see this battalion disintegrate in idleness? Would you have it said that our chaps can't do a proper job? Don't you realize how important it is to show these people that they can't break us, in body or in spirit? Take a good look, Clipton. One day the war will be over, and I hope that the people who use this bridge in years to come will remember how it was built, and who built it. Not a gang of slaves, but soldiers! British soldiers, Clipton, even in captivity.

The incredible build up is all worth it – the long film, the (perhaps) extraneous William Holden (as “Shears”) sequences, the near suicide of Hayakawa – it is all worth it for that moment when Nicholson discovers that it’s his fellow British soldiers who are trying to blow up the bridge. As if awaked from a trans, Nicholson says What have I done? Truly one of the greatest epiphanies ever filmed, both in terms of performance and payoff. Nicholson remembers that the bridge was his duty, but there was a greater one and it was for the British Army.

A final note – I thought I had this film figured out. It has remained in my memory as one of my formative movies. But rewatching it and discussing with the QFS group has introduced even more complexity into the story and the themes. Once again, the mark of a truly great work of art and craft by one of the masters of the medium.

Ace in the Hole (1951)

QFS No. 136 - I’ve managed to see a great deal of Wilder’s films but he made so many that there are a lot left for me to watch. He’s another one, like John Ford, with a very high batting percentage of great hits. I went with Ace in the Hole because, well, don’t we all want to bask in the glow of Kirk Douglas’ chin for nearly two hours?

QFS No. 136 - The invitation for March 27, 2024

This is our second Quarantine Film Society selection by the great Billy Wilder, after having seen one of his earlier films The Lost Weekend (1947, QFS No. 84) a couple years ago. Ace in the Hole (1951) has been on my to-see list for some time, so I’m very much looking forward to it.

I was tempted to select a Wilder film I’ve already seen because they are so rewatchable. And I’ve managed to see a great deal of Wilder’s films - Some Like it Hot (1959), Sunset Boulevard (1950), The Apartment (1960), Double Indemnity (1944) are such terrific classics - but he made so many that there are a lot left for me to watch. He’s another one, like John Ford, with a very high batting percentage of great hits. I went with Ace in the Hole because, well, don’t we all want to bask in the glow of Kirk Douglas’ chin for nearly two hours?

Reactions and Analyses:

One of the most surprising aspects of Ace in the Hole (1951) is that it’s from 1951 and not 1971. There’s an expectation for many of the post-World War II American films, that they have a Capra-esque quality. A happy ending or at least one that’s, at best, ambiguous or a qualified victory for the protagonist.

A happy ending Ace in the Hole certainly does not have. One of our group members highlighted a shot at the end of the movie, where the crowds have recently left and all that remains is Leo’s father near a sign that reads “Proceeds go to Leo Minosa Rescue Fund.”

It’s a shot that speaks to the fickle nature of the crowd, the spectacle over, and all that remains is the detritus of the carnival and a family in ruin. Leo (Richard Benedict) has died. His wife Lorraine (Jan Sterling) has departed with the masses, just as she intended to early on before Tatum (Kirk Douglas) convinces her that her fortunes will change soon. And Tatum, having used Leo and keeping him trapped longer than necessary in order for him to reap the benefits of the sensational story going viral before “going viral” was a term, also dies. But not before a final act of almost valor.

The 1970s – coming on the heels of New Wave moments throughout Europe which in turn came on the heels of Post WWII neorealism – featured a generation of filmmakers who were raised by people who had witnessed the horrors of humanity and understood that real life had no clean happy endings. Obviously, this is an overgeneralization but the trends are clear to see from the films that came to life in this era in the second half of the 20th Century.

With its social commentary on human nature and their attraction to spectacle, the media’s role in fanning the flames of that human nature, and a non-Hollywood ending Ace in the Hole feels like an independent film from the 1970s and not a studio release from twenty years earlier. You can easily see a throughline between this and Network (1976), a film whose very essence is an analysis of media, entertainment and sensationalism. The cynicism in Ace in the Hole feels uncommon for the 1950s, with the Cold War in its infancy and the Allies victory in World War II fresh in people’s minds. The fact that it’s Billy Wilder and that the film is twenty years before its time, in some respect, is perhaps why I’m so drawn to it now and why it has been rediscovered as an overlooked classic of the time.

Tatum says early in the film, “You pick up the paper, you read about 84 men or 284, or a million men, like in a Chinese famine. You read it, but it doesn't say with you. One man's different, you want to know all about him. That's human interest.” Tatum, as an anti-hero, displays a deep understanding of that human nature throughout Ace in the Hole. Sheriff Kretzer (Ray Teal) hates him but Tatum turns him around and knows what the sheriff most wants – to be seen as powerful and important. Tatum tells Sherrif Kretzer how he will promote the sheriff as the man most determined to save Leo and in exchange Tatum gets exclusive access to the mine and the metaphoric gold inside. He convinces Lorraine to stay in town and play the grieving wife because it will make her a star and make all of them money. Tatum is a devious genius and he almost pulls it off.

“Almost” is the operative word. His gamble has proven too costly and Leo dies. And here’s one of our primary debates happened in our QFS discussion group. In the end, does Tatum feel guilty? Is that what drives him at the end? He’s clearly devastated by Leo’s death – but is it because it ruins his own chance at stardom and the heights of journalistic fame? Or is it because he’s come to terms with the fact that he’s Leo’s “murderer,” that he directly caused Leo’s death and consequently has a moment of clarity?

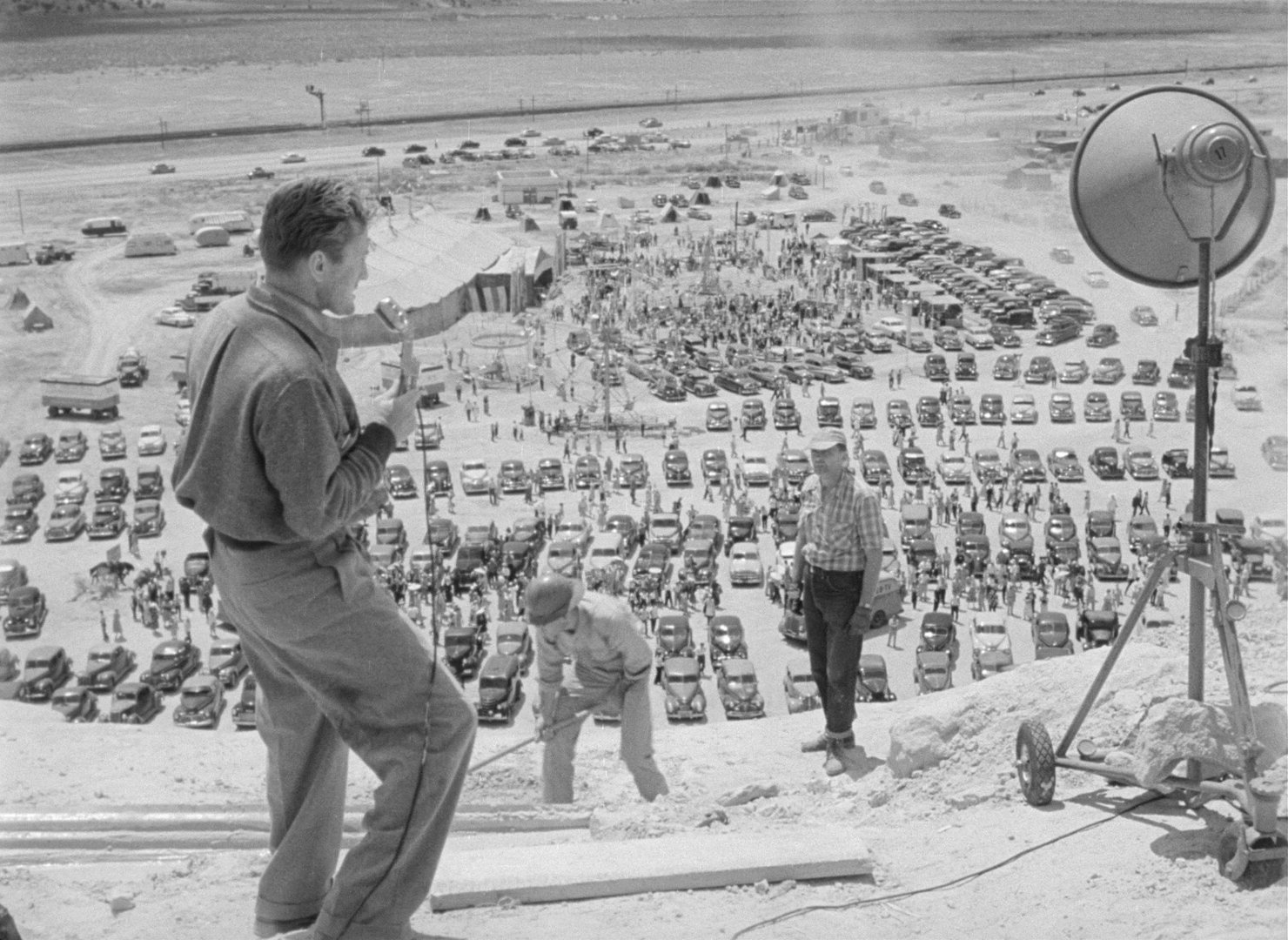

Several in the group believed that Tatum has no real remorse. Sure, he didn’t want Leo to die but he also knew that it meant the end of his own life. Others believed that he did in fact feel remorse and you can see it by his solitary act of bringing in the priest to comfort Leo for his final moments. Then, Tatum literally shouts from the mountaintop to tell everyone that Leo is dead and the carnival should go home. If he was truly in for all of this glory himself, he would’ve let Leo die quietly and had the “scoop” on Leo’s final minutes. (“Scoop” in quotes because Leo is the one creating this scoop.)

(Above sequence:) Tatum shouts from hilltop that Leo is dead. Is this the guilt-ridden face of a man full of remorse?

For me, personally, I think he did feel a measure of remorse and guilt but too little too late. And perhaps that’s why he doesn’t seek medical attention after Lorraine stabs him – he knows it’s his penance. He has to now suffer as he’s caused Leo’s suffering for his own gain. Perhaps explains why he accepts this pain without seeking amelioration or offering complaint, but it’s left (deliberately?) ambiguous.

People in our group brought up the cynicism but for me – and I said this early in our discussion – the film didn’t strike me that it was overtly cynical. And that probably says more about me or the time in which I live in now. For the 1950s, sure, the film is more cynical about human nature than popular culture portrayed. But we’ve now lived 75 years or so since then and seen the world revolve around capitalism, social media, hype, and the classically American propensity of squeezing money from every corner of human life. GoFundMe campaigns and “tribute” songs to raise money are the a logical extension of the funds to save Leo in the cave, the altruistic flipside of tragic spectacle.

And Leo – even the most “sympathetic” character in the film – is a grave robber of Native American artifacts! The person we’re cheering for to survive has, himself, stated that he’s probably cursed by the old spirits for robbing one too many times the burial sites of the indigenous of New Mexico. (Not to mention the studio so disliked the film that after its initial release they pulled it and remaned it “The Big Carnival” because people, you see, like carnivals so they might think it’s a fun movie! Talk about cynicism.) So it’s fair to say Ace in the Hole does have loads of cynicism – on screen and off – even though that’s not what first struck me.

The story is rife with plot holes as pointed out by the group, including the biggest one – why couldn’t Lorraine go down there to talk to Leo? It’s true – once Tatum goes down there frequently and it’s seemingly now safe to talk to Leo, then why can’t people who love him do that, like his parents? Also, is it believable that Tatum would suffer a stomach wound like that for so long? Only if he believes it’s a moral punishment.

And there’s this question – did Tatum ultimately win? He, too, is stuck in a hole – both he and Leo are in a hole together, one actual and one metaphoric. Both are counting on the other to extract them from their personal holes, but both die together. Tatum’s goal was to get back on top, become famous and return to New York. And while he doesn’t make it to New York and out of Albuquerque physically, he has become famous – people are cheering for him, the radio broadcast wants his exclusive thoughts. He is, for a moment, atop the world.

But it’s all fleeting, like the masses who come overnight and leave the next day as the tragedy ends. Ultimately, Tatum will become infamous and perhaps that’s victory enough – especially if you’re a cynic.

The Seventh Seal (1957)

QFS No. 127 - Sweden’s legendary director Ingmar Bergman is one of those essential filmmakers whose work you’re required to familiarize yourself with if you go to film school and intend to be a director. And with good reason. His films are deeply empathetic and explore what it means to be human in a style that I would characterize as part of the Neorealist movement that swept through post-war Europe.

QFS No. 127 - The invitation from November 8, 2023

Sweden’s legendary director Ingmar Bergman is one of those essential filmmakers whose work you’re required to familiarize yourself with if you go to film school and intend to be a director. And with good reason. His films are deeply empathetic and explore what it means to be human in a style that I would characterize as part of the Neorealist movement that swept through post-war Europe. But Bergman’s films have something even deeper and more meditative, a true journey into the soul that grapples with questions of morality and spirituality at their core.

Incredibly influential to filmmakers after him, Bergman wrote most of his own work and was a true auteur in film and television. Just look at some of his accolades – it’s pretty impressive to be Oscar-nominated five times for Best Original Screenplay when you’re not writing in the English language. To me, that’s astonishing. It’s a high bar for Academy members to look past the language barrier and to nominate a film for its written work - and Bergman did it five times over several decades!

For me, I’m still making my way through Bergman’s work – especially Persona (1966), Cries and Whispers (1972) and Fanny and Alexander (1983) which are high on my list of movies to see. His Wild Strawberries (1957), however, is a film I’ve seen in the theater and is a true masterpiece in its structure, style, pacing and exploration of a complex life lived. And, amazingly, he made it in the same year as he made this week’s selection The Seventh Seal. Two classics released in the same year has to be up there as one of the greatest single-year outputs by a filmmaker, rivaling Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 (The Godfather Part II and The Conversation) and Steven Spielberg’s 1993 (Schindler’s List and Jurassic Park).

As for The Seventh Seal – I’ve seen it once before but never in a theater so I’m looking forward to catching it at The New Beverly. I don’t want to ruin it for you if you haven’t yet seen it, but it’s probably the best Swedish movie to be spoofed in one of the films in the Bill and Ted’s Adventure Trilogy.

The Seventh Seal is an iconic, classic film and I’m excited to watch it again and discuss with you.

Reactions and Analyses:

Volumes have been written about The Seventh Seal and it has inspired a generation of filmmakers after it. The film comes out in 1957 and is perhaps one of the first instances in the West where the main thrust of the film is a philosophical one - is there a God and if there is, why is He/She/It silent? Not that a philosophical question hadn’t been posed in a film before, but here the film openly debates in both dialogue and in metaphoric action the philosophical question of whtehter or not there is a higher purpose. The knight Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) spends the entire time literally dealing with Death - an embodied death (Bengt Ekerot) in the form of a grim reaper with whom he plays chess. So the existential question of what comes after death is more than just an undercurrent - it is the current. Philosophizing about the existence of a higher power is not just theme it’s also plot in The Seventh Seal.

As someone who was not raised in the Christian tradition but grew up in a mostly Catholic neighborhood, some of the symbolism was familiar to me but there is a lot that I missed. So I turned to members of our group who had that religious background to fill in some details. One idea that came up was - is the knight dead the entire time? The film opens on the shoreline and the squire Jons (Gunnar Bjornstrand) lies facedown - dead? Sleeping? Even the knight is lying on his side when he sees Death approaching. Is it possible that he, like Christ, is close to death and dying himself and actually on a metaphoric cross contemplating the existence of God, begging for an answer? It might not be as straightforward as that, but there are definitely nods to this aspect of Christ’s divinity and story throughout.

Examples abound. There’s Jof (or “Joseph” played by Nils Poppe) and Mia (which is a Swedish abbreviation of “Maria,” played by Bibi Andersson) - Jof literally sees visions of the Virgin Mary with baby Jesus, of ghosts, of Death at the end, and Mia has an infant son Mikael (reference to the Archangel Michael?) with whom they travel around as itinerant performers. They gather a band of misfits and travel a ravaged, doomed countryside, rife with sinners and stricken by the plague at the end of the Crusades. The parallels to the life of Christ are easy to find if you just scratch the surface.

Aside from the symbolism, the central question Ingmar Bergman asks: with all this evil and destruction in the world, how is it possible there’s a benevolent God out there? From interviews, we know that Bergman was raised in a religious family and was terrified by death, seeing Albuertus Pictor’s church paintings depicting death playing chess against a knight. He says he wrote the film “to conjure up on his fear of death.” In the film we see a woman burned alive, a parade of people self-flagellating, people who died and just rotted away in place, others consumed by the plague. An entire village is empty. The group felt clear that Bergman answered the question, that the silence from heaven is what he fears - we are alone in a cruel world.

And yet, there’s the one scene where he is picnicking with Jof and their family. In the idyllic setting, with a slow pullback as he talks to reveal more of the setting, the knight says he’s truly happy. He’s saying that life is worth living here and now, and not for the afterlife because who knows whether there is one or not. For me, this scene is the one that gives me hope for the film. That there is beauty in the world, and that it lies in friendship and moments of sublimity. QFSers in the discussion pointed out that Bergman provides an answer of what to do if there is indeed no higher being - do good acts. “One meaningful deed” as the knight strives to do.

A film is not the same thing as an essay, and except for the most experimental films, generally speaking a film needs a plot. So aside from a parallel Christ story, Bergan borrows from other familiar literary traditions of the knight returning home, his squire at his side. There are echoes of Don Quixote and Sanch Panza, but without the fool’s errand aspect. Here in The Seventh Seal, the knight is the serious, questioning soul and the squire is the cynic, who says, for example, “Our crusade was so stupid that only a true idealist could have thought it up.” This is quite an indictment of someone who was part of waging a literal holy war. Although lightly plotted, the knight has a mission to ensure the life of that family - his one meaningful deed - all while keeping Death at bay. It’s this adventure tale, interwoven with the mystical, that keeps the film moving through the more philosophical aspects. And, for me at least, herein lies Bergman’s genius - you’re pulled in by the intriguing plot device and narrative, and you’re led to contemplate the meaning of something bigger as the story unfolds. Bergman asks: Are we alone? Bergman also answers: If we are, let’s do something righteous and live for the here and the now.

Forbidden Planet (1956)

QFS No. 119 - This is going to be an interesting one in that Forbidden Planet is (A) adapted from William Shakespeare and (B) we’ll be forced to take Leslie Nielsen seriously, he of Airplane! (1980) and the Naked Gun franchise fame.

QFS No. 119 - The invitation for August 9, 2023

This is going to be an interesting selection for us at Quarantine Film Society. Forbidden Planet is (A) adapted from William Shakespeare and (B) we’ll be forced to take Leslie Nielsen seriously, he of Airplane! (1980) and the Naked Gun franchise fame.

I’ve wanted to see this film for a little bit and I thought it’s time to return to pure escapist fare from an era before the special effects were super special but definitely inventive.

Join me in seeing Forbidden Planet and we’ll discuss!

Reactions and Analyses:

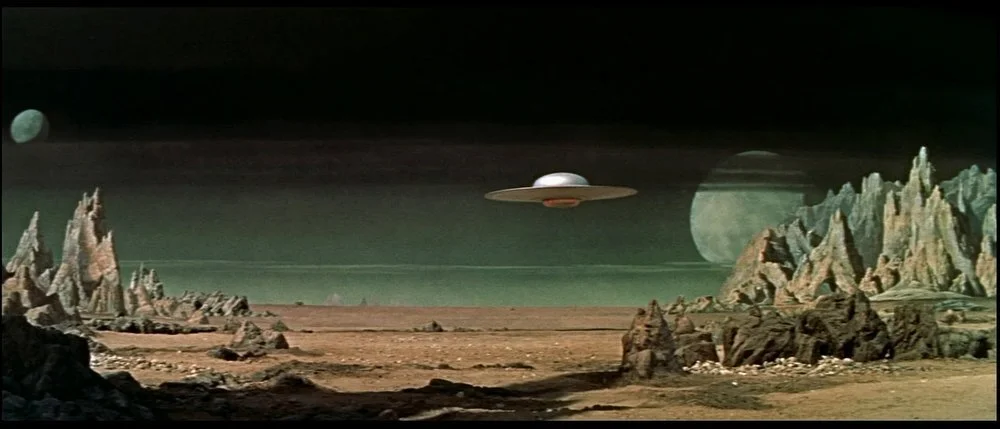

Watching Forbidden Planet with the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to see how influential it was to the next generation of filmmakers who expanded the possibilities of science fiction motion pictures. The entire film could be an episode of Star Trek, complete with the confident (and perhaps a touch pompous) captain and a mission by an Earth space agency in a time of great space exploration. As far as I can tell, this is the origin point of “hyperdrive” to propel a mission into space. Add a human-like docile Swiss-army-knife of a robot Robby and you get the serve as prototypes for hyperspeed, C-3PO and R2-D2 from the Star Wars universe all in Forbidden Planet.

The world created by Fred M. Wilcox in Forbidden Planet is vibrant and mysterious. He contrasts the drab greys and metallic colors of Commander Adams (Leslie Nielsen)’s crew with the pastels of the landscape and the lush tones of Dr. Morbius (Walter Pidgeon)’s home and interiors. Altaira (Anne Francis) prances in clothes that deliberately angelic and pure. The film, though science fiction, is a mystery set in a truly new world.

For all of the beauty in the world of Forbidden Planet – of which there is plenty – there lies at the center of the story a heady concept at its heart. Morbius was shipwrecked on this planet two decades earlier and is the only survivor, along with his daughter Altaira. In that time, they discovered remains of the Krell, a highly advanced species who became graceful geniuses and harnessed power in ways that dwarfs what humans have been able to do. Morbius, by using their machinery, has expanded his own mental power as well.

However, the Krell are gone. And the thing that killed them might be the very thing that wiped out Dr. Morbius’ fellow travelers two decades earlier – an unseen plague. That unseen plague steadily starts to eliminate members of Adams’ crew. So that’s the central mystery of the film. Who, or what, is the invisible monster on the island and can it be stopped?

At first, Morbius seems set up to be a mad genius villain. Yet, he’s perplexed by the monster on the island too. At first we’re led to believe it’s Morbius who is somehow responsible, that he’s cruelly eradicating all of his fellow Earthlings. And while it doesn’t lead us down that path too far, it does something surprising. The monster is Morbius. It’s his id – the part of his subconscious that is primal and instinctual, as described by Dr. Sigmond Freud. Fear, hunger, hate, shame – this creature is a manifestation of Morbius’ id.

And what brought about anger and fear from his id to create this creature? The visitors from Earth leering at his daughter. He fears her leaving, of becoming a woman, of choosing to go with Commander Adams and his crew and leaving him behind. And to be fair to Morbius, the men are very creepy. All of them are fawning over Altaira, with Adams going so far as saying that, well, what do you expect – you’re dressed like that and we’ve been trapped on a spaceship together for many months.

Ironically, it’s this aspect of the film that’s most dated and not the visual and special effects - it’s this obvious misogyny, tolerated or even accepted when the film. And moreover, she has never even seen a man who wasn’t her father, so how could she possibly know how to behave around them, even if Adams was right?

For their part, the visual and special effects hold up and are incredibly … effective … and at times spectacular. Perhaps except for Robby the Robot. Who everyone loves but definitely wouldn’t stand a chance against the likes of even the most simple of droids from the Star Wars Universe. (We mean no disrespect - Robby is a legend of filmand television.)

But the men do fall for Altaira and she for Commander Adams, hence justifying Morbius’ fears. As one QFSer put it in our discussion, it’s like a frat party just landed next to a house with a guy and his pretty daughter. Looking at it from this vantage point, I couldn’t help but feel like I understand Morbius – he’s acting out of primal need to protect his daughter from these creeps. So the film is heady and surprising in that way. There’s no traditional villain; Morbius is unaware of what he’s done to create the invisible creature from nightmares. However, the film doesn’t present Morbius in a sympathetic manner, focusing more on the hubris of a man who thinks he’s above it all since he unlocked higher intelligence. But all he’s done is push his baser instincts aside and created a monster.

This is quite difficult to follow and untangle at first since it’s all done in dialogue with one small twist: Robby is unable to shoot the creature. Because the creature is Morbius and Robby has been programmed never to harm a person. This is the one visual way Morbius - and the audience - finally understands that the creature is from Morbius’ psyche. Adams explains it all but it’s difficult to comprehend while the id monster is crushing doors and bearing down on them. In some ways, though, the scariest creature is one you can’t fully see - and this one, we only see once while it’s caught in the electric fence. That one time is terrifying enough and gets great mileage for the remainder of the film.

Despite some of these gaps and missteps, Forbidden Planet is incredibly enjoyable. Robby the robot is actually too great of a robot. Any robot who can both make a dress from scratch as if putting in A.I. prompts or can make 60 gallons of bourbon after “sampling” some of it (and burping), is a dream come true. He drives like race car driver and has gentlemanly manners to match. If anything, Altaira should be paired with Robby the Robot.

Ten years after Forbidden Planet Gene Roddenberry’s series Star Trek debuts on television, and eleven years later, Lucas makes Star Wars (1977). Going back to Forbidden Planet after seeing those two expansive successors feels like visiting an original text. Science Fiction has been around from before the invention of the motion picture. And once the motion picture was invented, science fiction became one of its primary genres. Yet, it’s easy to see how our two biggest tentpoles for Science Fiction began here, with Forbidden Planet, long ago on Altair IV in a galaxy far far away.